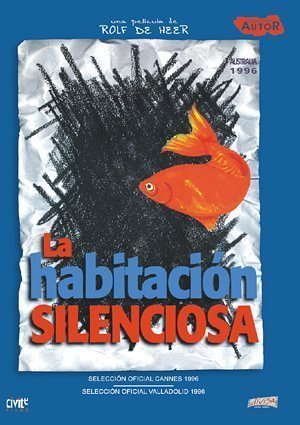

QUIET ROOM, THE

(director/writer/producer: Rolf de Heer; cinematographer: Tony Clark; editor: Tania Nehme; music: Graham Tardif; cast: Celine O’Leary (Mother), Paul Blackwell (Father), Chloe Ferguson (Girl Age 7), Phoebe Ferguson (Girl Age 3), Kate Greetham (Kate, the Babysitter), Todd Telford (Workman); Runtime: 93; MPAA Rating: PG; producer: Domenico Procacci; Fine Line Features; 1996/Australia)

“The Quiet Room was a little too quiet for me.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

This is a stagy psychological picture that falters despite intelligently reflecting on the emotions of a seven-year-old girl. It becomes wearisome when it stays with its gimmicky voice-over throughout the film. A whimsical and oversensitive girl (Chloe Ferguson) gets mad at her parents (Paul Blackwell & Celine O’Leary) for not getting along and arguing over petty things, and decides to stop talking in protest. Chloe talks to herself and the audience hears what’s running through her mind via the voice-over. Unfortunately, the film fails to be cinema friendly and this gimmicky approach to understanding where the child is at, is just not very entertaining. We can almost see the camera lingering with studied sluggishness over the family. Though, I must confess, seeing the film totally through the child’s viewpoint had moments of clearly showing us her fears, yearnings, and emotional balance. But this breakthrough came at the expense of any dramatics or tension. The film was so set in its static ways that it seemed too pat to do anything more when it unlocked the thoughts from the girl’s head and had them pour out in a free association stream of consciousness. The thought process of the youngster watching her parents’ marriage coming apart was hard for me to relate to, probably because I couldn’t imagine myself at that age thinking like this girl. Maybe it’s a gender thing, but I think it’s more than that. I can certainly understand how threatened the girl feels by her parents’ rift and her desire to have a loving home, but I can’t see her articulating her feelings in such a mature way even if her thoughts are shown to be properly childish and that she often misunderstands the situation. Children of her age just don’t talk like that, not even to themselves. At least, I don’t think they do. I thought this was a construct by the writer and director, and was mostly a case of trying too hard to make a point of how affected and aware children are of problems at home. Of course children are deeply affected when they see their parents’ arguing, there’s no arguing that, but other than finding the film to be original I didn’t find its formal presentation persuasive.

Rolf de Heer (“Tail of A Tiger“/”Incident at Raven’s Gate“/”Bad Boy Bubby“) was born in Holland in 1951 but moved to Australia when he was eight. He graduated from Australia’s prestigious Film, Television and Radio School. De Heer seems to be interested in pushing the boundaries of both form and content in low budget filmmaking. In “The Quiet Room,” I admire the idea behind the project more than I do the film.

The film opens as a seven-year-old girl watches her goldfish, plays with her dolls, draws pictures with her crayons. The unnamed girl is in her quiet room–a blue-walled bedroom. Her mother brushes her long blonde hair and helps put on her school uniform. Her father leaves for work and kisses her mother good-bye. Even though this seems like the normal family routine for a schoolday morning, the girl senses that something is wrong. She remembers how things were better when she flashbacks to herself at three (Phoebe Ferguson, the real-life sister of Chloe), and wonders what went wrong. But the seven-year-old cannot express her emotions, and believes that words themselves may be the problem. So she stops talking, as she cries out for more attention from her well-meaning parents.

Chloe’s parents still play with her and read to her, but what’s happening in the home leaves her feeling she has little control over the situation. She’s also affected that her goldfish keep dying, and she can’t hatch a chicken egg. What the girl yearns for is to live in the country and have a pet dog, and she hopes by living in a house instead of an apartment the love will return to the household.

This unique film reminded me of My Life As A Dog and Careful He Might Hear You. In “The Quiet Room,” the director claims “I wanted to give kids credit for who they are, really.” He goes on to say, “For me, it was important to work at that balance of when she’s perceptively correct and when she makes completely the wrong conclusions.”The filmmaker goes on to mention that “he has very strong memories of his own childhood, and feels that adults too frequently disregard children as having feelings because they do not have a proper vocabulary and the ability for conceptual thinking to express themselves verbally.”

The film slowly builds to its climax, as the excitement revolves around whether the child will freely speak and what she will say. The film’s point of view is so correct that only a cad would argue with it. My dispute is that I didn’t feel thrilled sitting around for such a long time twiddling my thumbs in boredom as I was spoon-fed something that I more than got about a quarter of the way into the film.

This four-character film is well-acted. Paul Blackwell and Celine O’Leary give selfless performances as the parents that allow little Chloe Ferguson to shine as the girl who takes the adult audience on a trip into her childhood world. When the girl smiles, she lights up the screen. My heart goes out to her, but I was not deeply affected by the film. The Quiet Room was a little too quiet for me. It was basically a one-idea movie.

REVIEWED ON 4/1/2003 GRADE: C