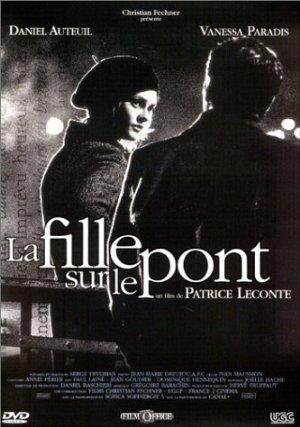

GIRL ON THE BRIDGE, THE (La Fille sur le Pont)(director: Patrice Leconte; screenwriter: Serge Frydman; cinematographer: Jean-Marie Dreujou; editor: Joelle Hache; cast: Vanessa Paradis (Adèle), Daniel Auteuil (Gabor), Demetre Georgalas (Takis), Isabelle Petit-Jacques (Takis’s bride), Frédéric Pflüger (the contorsionnist), Giorgios Gatzos (Barker), Bertie Cortez (Kusak), Luc Palun (Stage Manager), Catherine Lascault (Irene); Runtime: 92; Paramount Classic; 1999-France)

“It is artfully directed byLeconte with his choppy camera work matching the Mediterranean’s bubbly sea movements and the trembling nature of the feature players.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Patrice Leconte (“Monsieur Hire” (1989)/ “The Hairdresser’s Husband” (1990)/”Ridicule” (1996)) has created an original and strangely beautiful B&W film, one that has its roots buried somewhere in French New Wave cinema and in Fellini’s road film La Strada. It is artfully directed byLeconte with his choppy camera work matching the Mediterranean’s bubbly sea movements and the trembling nature of the feature players. His smoothly dark photography makes it seem as if he’s filming a 1940s noir work and his eclectic musical background soundtracks (ranging from Benny Goodman to Marianne Faithfull and from Italian to Turkish music) adds an excitement to a story that changes moods from comical to tragical at the drop of a knife. It should be noted, in the director’s biggest joke he has with the audience, how the background music plays a large part in the enjoyment of the film. This is shown when the knife-thrower hits his human target, as Brenda Lee croons her song “I’m Sorry” and the Italian woman target is carried off on a stretcher to the hospital.

The gist of the story revolves around an eccentric romance between two desperate souls, one childish and trusting, the other jaded and mystical. When the film is playful and lighthearted, it is sublime and masterfully done. Unfortunately when the last reel comes the film shifts gears and starts to take its philosophical musings about chance and luck seriously, and the film becomes contrived and loses much of its punch.

The power in the film’s punch comes mostly from the imaginative performances of international pop star Vanessa Paradis, the girlfriend of Johnny Depp, and from one of France’s most popular and best actors, Daniel Auteuil. She was nominated for a Cesar as Best Actress and he won a Cesar as Best Actor. These two have an electricity together that is, indeed, magical. Both have very expressive facial gestures and large eyes that open wider when welcoming the viewer into their story in a most hospitable way.

Girl on the Bridge ran as a mainstream film in France, while in America it has only played in art-houses. Perhaps any film with subtitles (especially subtitles that are hard to read) and one that is shot in black-and-white, can only be relegated to a select audience in the States. Or, maybe, a knife-thrower act in a circus venue is art in America, while in Paris it might be viewed as the old — seen that, done that thing.

The film opens to the beat of exotic Algerian music in the background and a gap-toothed cutie of almost 22-years-old named Adele (Vanessa) is being interviewed by an official sounding woman, who could be a social worker, court official, or shrink as the questioner is never seen or identified, and no reason is given for why Adele is sitting in a bare room by a table and answering personal questions. Adele tells her hard-luck story in a matter-of-fact way from the start of her nymphomania and life of wandering from one man to another, to her current feelings of depression. She is so persuasive, that we know everything about her that we have to from this brief opening look at her, so much so that when she shifts her eyes we even know what she is thinking.

The next time we see Adele, she’s shivering and contemplating suicide by jumping off a bridge overlooking the Seine River. Suddenly Gabor (Auteuil), a middle-aged, has-been, philosophical knife-thrower, reveals himself and tries to talk her out of jumping even offering her a job as his assistant, which in this case means being a human target for his act. Gabor is on a recruitment mission, figuring that he is offering this dangerous job to someone who is prepared to die anyway and therefore should not be frightened off by the risks involved.

Nevertheless Adele jumps into the water, and Gabor jumps in to save her. Now that’s the start of a lifetime friendship, if you ask me. The girl not only seems grateful that Gabor cared enough about her to come to her rescue, but he makes it possible for her to win his expensive watch by playing a gambling game with her (never mind that we soon see that he has many other watches in storage, it is the thought that counts). They are now ready to begin their partnership and they start by traveling to the south of France, where Gabor books them into a circus at Monaco. In order to get the job there, Gabor volunteers to do a risky blind knife-throw. Adele is so naive, that she has no idea of what she is getting into. The knife-throwing is played as a metaphor for sex, as Adele erotically gasps as the knife is thrown at her while she’s wrapped around a sheet. There was something bizarre about the act that was movie magic…fake magic, I grant you, but magical enough to keep me glued to my seat in anticipation of what will happen to her–as Leconte also had the circus sideshow entourage gasping with concern. I think he might even have expected the theater viewer to be masturbating over this.

The catch to their relationship is that it is a chaste one, one that allows Gabor to have a telepathic relationship with Adele as they read each other’s thoughts; but, it is one that does not prevent her from having sex with any man who catches her fancy and to add to her sexual prowess, she is keen on doing it in odd places and positions. My favorite tryst was Adele and the contortionist making it on top of the piano (the sex act itself is only imagined and is tastefully not seen — but can you imagine how they did it?). The director also makes a concerted effort to show that Gabor is normal sexually in the biblical sense, by showing a brief encounter he has with a former girlfriend (Lascault) in the circus.

Gabor discovers he can change his bad luck with her as his partner firmly believing that she’s his lucky charm he has been missing, and he sends her off to the gambling casinos in France and then the Italian Rivera to play roulette and baccarat and she amasses a small fortune. They are sitting on top of the world and he also begins to show his true feelings which indicate he’s falling in love with her; but, staying in character, he can’t spit it out and tell her. Besides, sex would ruin the mystical relation they have in the act and the luck they have in her gambling.

Their downfall which parallels the film’s, is when they are on an Adriatic cruise ship as performers and Adele meets a newly-wed Greek named Takis and decides he is her Mr. Right; Adele literally jumps ship with him and flees the cruise ship on a small boat. Adele falls for his fake kindness and believes him when he says: “My wife is Italian: we don’t communicate with each other.”The film then moves off the map of credible film-making and becomes silly and contrived, probably imitative of those cartoon-like action films, showing a helicopter rescue of the couple adrift at sea. For a film that was so sublime and had such an enchanting mystical romance going for it, it foolishly throws that all away to make its cheap points about chance. It also preaches, that two souls that fit together should not separate and are compared to a money bill that is valuable only if it does not get torn apart. That is too heavy-handed a message for this bubbly film to handle.

The film should have been a more far-reaching one and it could have been much funnier if it didn’t go on the wrong cruise toward the end. But what we have is still a visually spellbinding film and one where Vanessa and Danny prove to be very human creatures, who are worth caring about. Though the part where he ends up in Istanbul selling his knives after his luck (Adele?) ran out, didn’t convince me that he so suddenly lost his edge on life; and, therefore it made me rethink what I was asked to believe about the two lost souls. What I still came up with is that they are both good at flirting with disaster but what they both have in spades, is a whimsical sense of humor and a strange sense of survival. And, just like Serge Frydman’s script which was both witty and superfluous, the film nevertheless succeeded in sucking me into its smart story.

REVIEWED ON 12/2/2000 GRADE: B