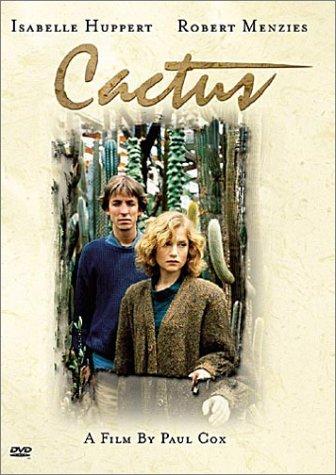

CACTUS

(director/writer: Paul Cox; screenwriters: Bob Ellis/Norman Kaye; cinematographer: Yuri Sokol; editor: Tim Lewis; cast: Isabelle Huppert (Colo), Robert Menzies (Robert), Norman Kaye (Tom), Monica Maughan (Bea), Banduk Marika (Banduk), Peter Aanensen (George), Sheila Florance (Martha), Sean Scully (Eye Doctor), Julia Blake (Club Speaker), Jean-Pierre Mignon (Jean-Francois); Runtime: 96; MPAA Rating: PG; producers: Jane Ballantyne/Paul Cox; Image Entertainment; 1986-Australia)

“It seems like a 19th-century Victorian tale.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Paul Cox (“Man of Flowers”/”My First Wife”) is the director and co-writer, along with Norman Kaye and Bob Ellis of this spare, quiet and sensitive romantic melodrama. Colo (Isabelle Huppert), a young Frenchwoman visiting friends Tom (Norman Kaye) and Bea (Monica Maughan) in Australia, is separated from her back home hubby Francois (Jean-Pierre Mignon). She gets into a car crash and severely injures her left eye, and in order to save the partial vision in her right eye is told by the eye doctor that the left eye has to be removed. Left in a state of shock, Tom introduces her to the wealthy loner Robert (Robert Menzies) who grows in his greenhouse cacti. He was born blind and has made the best of his handicap by becoming independent (he shows his love for the prickly plant by caressing it and saying they need his special care but recognizing that they grow best when ignored). A romance blooms between the two, as each of them come out of their shells: he learns to care about something other than his precious cacti and she learns to face her handicap with courage.

It’s a bitter-sweet elegant sudser that never descends into sentimentality or banality, though it flirts with falling into that pitfall making one recoil at times with stilted dialogue such as Robert shamelessly saying: ”Wounded animals should be left alone.” It’s saved from wilting by its striking classical music soundtrack, a fine use of flower symbolism, superb performances, tricky digital photography in the many flashbacks that make even car crashes seem bloodlessly lyrical and a smart usage of blurred photography to show the tension caused by losing one’s eyesight, a well-thought out script, lush Eden-like landscapes that even a blind person can picture because of its evocative rich sounds, and its classy way of letting its solemn story gradually unfold with sprinkles of subtle humor (hostility surprisingly unveiled in a club lecture on cacti and its many inconsequential but humanizing moments where the younger woman is in the company of Tom’s older eccentric friends).

In the end, the Huppert character views the handicap of blindness as a chance to reach a greater self-awareness and must readjust to make the best of a bad situation. She now has to make tough decisions such as whether to stay in Australia or return home to an unhappy marriage, and whether to remove her eye as advised by the doctor. The Huppert character has been given another chance to learn about herself and now must learn how to communicate without her old selfish ways.

It seems like a 19th-century Victorian tale, where being surrounded by the lush serene countryside and partaking in gentle conversations among the intelligentsia count for more than leading a ribald life or having perfect vision.

REVIEWED ON 3/31/2006 GRADE: A-