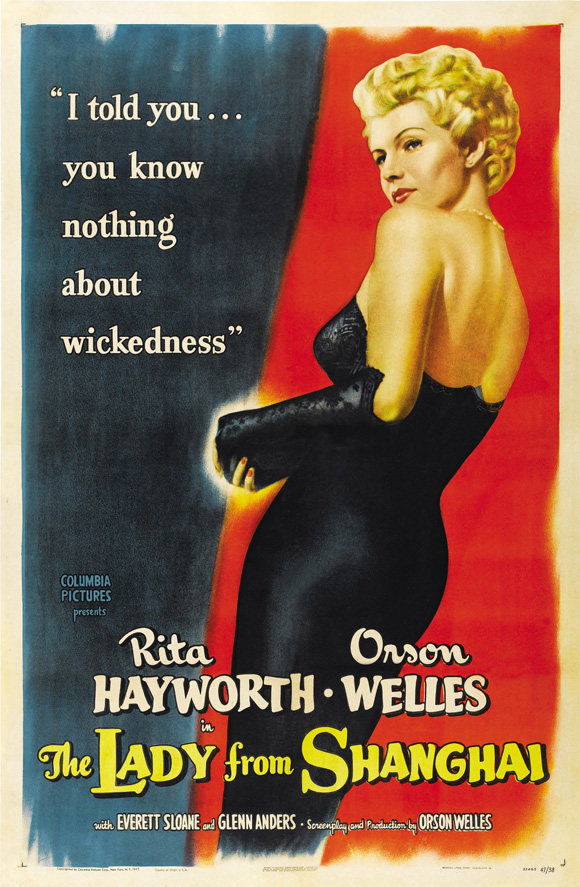

LADY FROM SHANGHAI, THE

(director/writer: Orson Welles; screenwriter: from the book Before I Die by Sherwood King; cinematographer: Charles Lawton; editor: Viola Lawrence; music: Heinz Roemheld; cast: Rita Hayworth (Elsa “Rosalie” Bannister), Orson Welles (Michael O’Hara), Everett Sloane (Arthur Bannister), Ted de Corsia (Sidney Broome), Glenn Anders (George Grisby), Erskine Sanford (Judge), Gus Schilling (Goldie), Lou Merrill (Jake), Evelyn Ellis (Bessie), Carl Frank (District Attorney); Runtime: 87; MPAA Rating: NR; producers: Harry Cohn/Orson Welles; Columbia Pictures; 1948)

“A masterpiece in the bizarre and the complex.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A masterpiece in the bizarre and complex. Orson Welles’ (“Citizen Kane”/”The Magnificent Ambersons”) weirdly plotted tongue-in-cheek film noir is based on the book Before I Die by Sherwood King. It costars Orson with his estranged wife Rita Hayworth, who plays the unfeeling seductive femme fatale beauty Elsa Bannister. She seduces the innocent roughhouse drifter sailor with the thick Irish Brogue, Michael O’Hara (Orson Welles), while alone in a Central Park coach, and after he rescues her from muggers she recruits him through her husband to be a crew member aboard their luxury yacht bound for a pleasure cruise in the Caribbean. The philosophizing sailor learns she’s married to wealthy, brilliant, crippled lawyer Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), considered the best in his field. Elsa goes on the trip with her hubby and his two cronies, Goldie and Jake, and Michael joins them because he’s hooked by her beauty.

On the cruise, Michael has an affair with Elsa which is spotted by Bannister’s eerie law partner, with the unique cackling voice, George Grisby (Glenn Anders). He joined the yacht en route. Michael gets turned off by the lot of them, as he considers them sharks. Even though Michael once killed a man who was a Franco spy during the Spanish Civil War, he’s a babe in the woods compared to this crew of heavies. The men spend ship time drinking heavily and take glee in cutting each other up with words, while Michael provides the comical voice-over explaining his disgust with them and himself for being so stupid to join them. Bannister takes note of Michael’s naiveté by saying: “You’ve been traveling around the world too much to find out anything about it.”

Warning: spoiler to follow in next two paragraphs.

Returning to San Francisco Michael fails in trying to talk Elsa into leaving her creepy hubby and running off with him. Figuring he needs some cash to satisfy the lady, he foolishly accepts an offer from Grisby to fake his death and receive $5,000. Michael also has to sign a confession, but is assured by Grisby that since no corpse will be found he can’t be convicted. Grisby reasons he can collect on an insurance policy the partners have that stipulates in case of either’s death the other collects. But things get botched when the butler, Sidney Broome (Ted de Corsia), who is really a private detective hired by Bannister to spy on his wife, gets wind of Grisby’s murder scheme and smells a rat. Grisby kills him and is later killed himself, and the innocent Michael gets framed for the murders. At the murder trial, he’s defended by Bannister. It becomes apparent that Bannister, who never lost a case, is fixing on losing this one. Before the expected guilty verdict is announced Michael escapes to a Chinatown playhouse and Elsa, through help from her Chinese associates, helps him flee to an abandoned Chinatown amusement park. But Michael has come to his senses at last and realizes that he’s been used by Elsa as a pawn in a complicated plot to murder her hubby and then her hubby’s killer Grisby.

At the Crazy House, in front of the hall of mirrors, Bannister goes after his unfaithful wife knowing that she was behind the plan to kill him. The film is remembered for this great scene of multiple mirrors reflecting the same image, as the strong innovative visual style elevates this illogical baroque nightmare into a compelling work of cinema magic–complementing the pleasurably murky narrative about lust, greed, and betrayal. It’s offered as a commentary on the grotesque world, as the reflecting mirrors serve as a metaphor for how we are busy killing ourselves but don’t know it.

Biographers have asked if this story pertains to the break-up of Orson’s real marriage with Rita, and critics and columnists have had a field day filling in the blanks with gossip.

The film, reedited by the studio and taken completely out of Welles’ hand and cut from its over two hour length to 90 minutes, became a b.o. disaster and exiled Welles from Hollywood for almost a decade (until Touch of Evil in 1958). It makes you wonder how any great film ever gets made, since Welles is not the only great filmmaker treated with such contempt by the studios, the mass public and the critics.

REVIEWED ON 1/6/2005 GRADE: A+