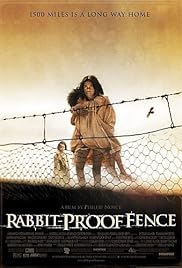

RABBIT-PROOF FENCE

(director/producer: Philip Noyce; screenwriters: from the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington/ Christine Olsen; cinematographers: Christopher Doyle/Brad Shield; editors: Veronika Jenet/John Scott; music: Peter Gabriel; cast: Kenneth Branaugh (Mr. Neville), Everlyn Sampi (Molly Craig), David Gulpilil (Moodoo), Laura Monaghan (Gracie), Tianna Sansbury (Daisy), Tamara Flanagan (Escaped Girl), Ningali Lawford (Molly’s Mother), Myarn Lawford (Molly’s Grandmother), Jason Clarke (Constable Riggs), Natasha Wanganeen (Dormitory Boss, Nina), Deborah Mailman (Mavis); Runtime: 95; MPAA Rating: PG; producers: Christine Olsen /John Winter; Miramax Films; 2002-Australia)

“Noyce films it more as a shocking history lesson than as drama.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Aussie director Phillip Noyce (“The Quiet American“/”Patriot Games“/”Clear and Present Danger“/”The Bone Collector“) directs a heartbreaking true story with the tagline “What if the government kidnapped your daughter?” It’s a story about Aborigines in Western Australia from the Jigalong village (a depot for the transcontinental fence), which is scripted by Christine Olsen from the book “Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence” written by Doris Pilkington. Ms. Pilkington is the daughter of the story’s heroine, Molly Craig (Everlyn Sampi). It’s one of those weepie human drama miscarriage of justice stories where the line drawn between justice and injustice is so clear, that the audience is left to only gasp in horror at how mean-spirited the law is that allowed in 1931 the state to take away half-caste Aborigine children forcibly from their parents and raise them in white-run orphanages that would prepare them for lives as domestic servants and force them to only marry each other and to forget about their culture for the white Christian one and their language (mockingly called jabber by their teachers, as they force their charges to speak only in English). This blatant racist philosophy of genocide was accomplished under the aegis of giving their charges a Christian education to integrate them into the so-called superior white society while keeping them from being absorbed into a black culture, where because of their white genes the fear was that they might provide the blacks with sparks of leadership for an uprising. The pasty-faced white man, who is the villain in charge, is the stern and self-righteous Mr. Neville (Kenneth Branaugh), with the fancy title of Chief Protector of the Aborigine Populace. His performance was low-keyed and chilling, a monster if there ever was one, as the usually hammy Branaugh does a good job in depicting the banality of evil. He was referred to by the children as Mr. Devil. He believed it would take three generations of further mixing their blood with each other to wash out their blackness, as the aim was to get rid of this half-breed problem in what was amazingly thought to be a Christian way. Nurses dressed in white uniforms (they looked like a women’s branch of the KKK) ran things with an iron-clad discipline and a cold-hearted disregard for the welfare of the children. In the dining hall one had to pray with their eyes closed before being fed, and in the dormitory all the girls slept in one large room and slept in unclean bunks. An escapee when caught would be punished with a severe whipping. It sounds like a policy the Nazis could have lived with. This policy was in effect from 1905 until it was abolished in 1970.

The film follows the three girls, Molly Craig age 14 and her sister Daisy age 8 (Tianna Sansbury) and her cousin Gracie age 10 (Laura Monaghan), who escape from the Moore River Settlement School and follow the “rabbit-proof” fence (the longest fence in the world; it runs 1500 miles across the country and is made up of at least three such fences that were put up to keep the rabbits from overrunning the agricultural land) to travel nine weeks on foot and some 1200 miles to go back home to the desert outback and their loving mother (Ningali Lawford) and grandmother (Myarn Lawford). These biracial children had Aborigine mothers and white fathers who worked on the fence and then abandoned them.

Most of the film is about the girls’ epic journey north to their home and how they were followed by the police and a conflicted, withdrawn, stoic, aboriginal tracker Moodoo (David Gulpilil), armed with a whip, whose daughter is also at the Settlement and he hopes that he can strike a bargain with Neville to get her out some day (but he didn’t seem too anxious to find the girls). The girls under Molly’s courageous and determined leadership hide their tracks and undergo a series of adventures to avoid their relentless pursuers. They received food and clothes from one white woman (Mailman) and some help from others on the way, while some acted as hindrances.

It’s the story about “strength of spirit” and a will for freedom. The children who suffered this cruel fate were termed as members of the “Stolen Generations.” It is interesting to note that the Australian government has never formally apologized for these inexcusable practices, not even at this late date. Though, a government report was issued in 1997 comparing this policy to genocide.

The three young girls are all aborigines, nonprofessionals, and had to audition for the parts that many tried out for as a result of a country-wide search. The film’s star, Everlyn Sampi, has this amazingly powerful look that goes right through you. Everything about her is striking and noble and sincere, as Everlyn’s sparse dialogue emitting only well-chosen words with a precise diction leave a lasting impression of her vulnerability. The girls were not required to do much more than look the parts they played, but their look seemed to be enough.

The rich red dirt landscape and the sweeping exterior shots of the rugged terrain from the camera of Christopher Doyle, make for eye-popping shots of the barren frontier. The soulful traditional Aborigine music mixed in with the contemporary New Age music by Peter Gabriel was effective in setting the mood of excitement for the runaways.

As for the integrity of the girls’ performances and the well-meaning intent of the story, there’s no argument about that. But Noyce films it more as a shocking history lesson than as drama. Its aim was to be heartfelt and it easily accomplishes that aim. Though is was moving, everything seemed too obvious to inject any kind of dramatic tension. It was the kind of film that made it too easy for the audience to identify with the abused girls and despise the white devils who enforced such racial bigotry, and therefore it made it too easy for them to feel superior to the villains. But it let everyone else in the country who should have known better off the hook. The politics of this disgraceful practice was all but ignored. There was something deeper to dig out of this, but Noyce never bothers. He seems satisfied with keeping this compelling story as merely a rebuff to racism. The result is a safe pic (though I’m told some whites in Australia protested) even though he’s handling an emotionally charged real-life story. It was in need of some more fervor, perhaps a craziness that someone like a Ken Russell injects into the underbelly of his pics. Good intentions are not enough to make this pleasing film seem like much more than ordinary, when the true story is anything but ordinary.

REVIEWED ON 2/15/2003 GRADE: C +