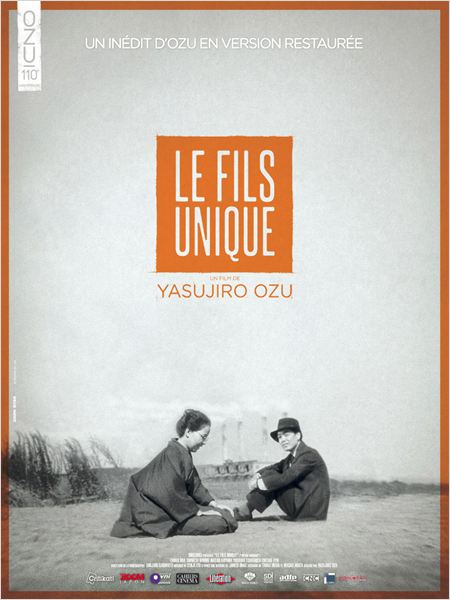

ONLY SON, THE (HITORI MUSUKO)

(director/writer: Yasujiro Ozu; screenwriters: Tadao Ikeda/Masao Arata/short story by Yasujiro Ozu; cinematographer: Shojiro Sugimoto; music: Senji Itô; cast: Chishu Ryu (Professor Okubo), Tomoko Naniwa (Okubo’s wife), Bakudankozo (Ookubo’s son), Choko Lida (Tsune Nonomiya), Shinichi Himori (Ryosuke Nonomiya, the only son of Tsune), Masao Hayama (Ryosuke Nonomiya, as child), Yoshiko Tsubouchi (Sugiko), Mitsuko Yoshikawa (Otaka), Tomio Aoki (Tomi); Runtime: 87; MPAA Rating: NR; Shochiku Company; 1936-Japan-in Japanese with English subtitles)

“It’s the noted director’s first talkie and one of his best signature family dramas.“

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

It was meant as a silent film based on the earlier script, Tokyo is a Nice Place, by Yasujiro Ozu (“What Did The Lady Forget?”/”An Inn in Tokyo”/”Dragnet Girl”). It’s the noted director’s first talkie and one of his best signature family dramas about a mother’s love for her child, but is also one of his darkest films offering little hope. It seems like a silent, with long takes from a motionless camera and little dialogue. Cowriters Tadao Ikeda and Masao Arata provide a moving script of a self-sacrificing mother who believes that by giving her child an opportunity to be a college graduate will inspire him to be a great man.

In 1923 in the rural impoverished city of Shinshu the aging widow Tsune Nonomiya (Choko Lida), a poor loom worker in a silk mill, follows the suggestion of her son Ryosuke’s (Masao Hayama) kindly elementary school teacher, Professor Okubo (Chishu Ryu), and agrees to pay for her son’s high school education as he boards out of town. In 1936, after not seeing her now young adult son (Shinichi Himori) for all those years she visits him in Tokyo, and is shocked to find that he has lost his municipal job (which is never explained why) and is working at a low paying unimportant job teaching in a night school, lives in poverty in a bleak part of town and in a shabby house, and has not told her he has married Sugiko (Yoshiko Tsubouchi) and has a young son. Ryosuke’s ashamed that he disappointed his mom, who has even sold her house to live in the factory dorm to support him. Mom tells him she’s disappointed and that he must not give up so easily. Later when his neighbor Otaka can’t pay the hospital bill when her son Tomi is kicked by a horse, Ryosuke pays the medical tab with the money meant to show mom a good time in Tokyo. Mom sincerely tells him that even though he’s not a success, he at least turned out to be a decent person. But, in her heart, that doesn’t mean she’s not disappointed with him.

Mom’s true feelings are signaled with the glum ending, as she returns to the depressing factory as a cleaning woman and while scrubbing floors cheerfully tells the other cleaning woman that her son became a great man. But when back at the dorm, which looks as depressing as a prison yard, her sad expression as she sits alone tells us that she might not think of her son as a failure but more as a disappointment since she had such high hopes that he could have a better life than she did and that didn’t pan out.

For Ozu, the parents’ high expectation for their children will usually fall short and cause them unneeded grief. Ozu also offers a social commentary how in 1936, in Japan, 44% of the college grads couldn’t get jobs to fit their education and most walked around with low self-esteem feeling like failures, as he shows even the capable Professor Okubo can’t get a decent teaching job after moving to Tokyo and is forced to run a small cutlets restaurant. The introspective melodrama entertains in a bittersweet way how difficult it is to climb the ladder out of poverty, how you cannot even trust those closest to you to tell the truth, how life’s inevitable disappointments and betrayals from relationships sting and how it’s almost impossible to understand someone else’s life from only your perspective.

Like most of Ozu’s films it was critically acclaimed, but at the box office it barely broke even.

REVIEWED ON 4/13/2010 GRADE: A