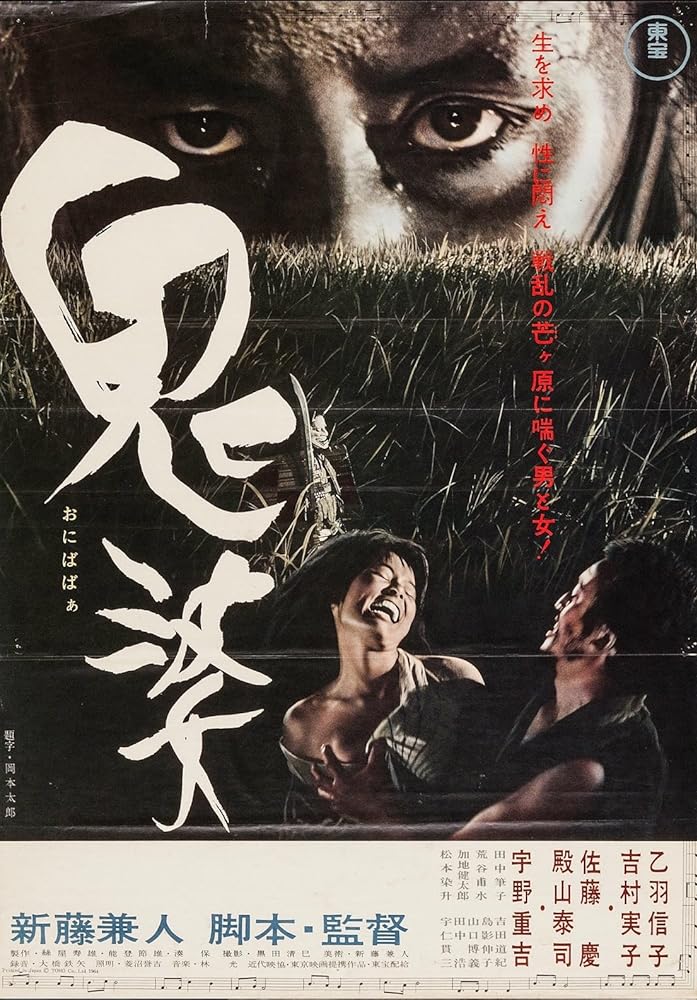

ONIBABA (HOLE, THE)

(director/writer: Kaneto Shindo; cinematographer: Kiyomi Kuroda; editor: Toshio Enoki; music: Hikaru Hayashi; cast: Nobuko Otowa (The Mother), Jitsuko Yoshimura (The Daughter-in-Law), Kei Sato (Hachi–the Farmer), Jukichi Uno (The Warrior), Taiji Tonoyama (Ushi–the Merchant); Runtime: 103; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Toshio Konya; Janus; 1964-Japan, in Japanese with English subtitles)

“Interesting as a claustrophobic vision.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A visually arresting allegory in the form of a costume horror/ghost film as directed and written by Kaneto Shindo. It’s set in feudal Japan’s 16th century in the midst of a seemingly endless civil war, where the rival Asikaga and Kushnoki armies have destroyed Kyoto and the territories are now ruled by two emperors. It’s said that the casualties are so great, that a black sun rises in Kyoto. The title translates to The Hole, as the tale refers to an ancient legend involving an elderly woman (Nobuko Otowa) and her much younger robust and attractive daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura). They are peasant farmers in an isolated village surrounded by body-high reeds, and earn their living by luring and then killing stray samurai escaping the war and selling their armor to the unethical merchant Ushi to buy rice. After they kill and strip their victim of his possessions, they dispose of him in a deep black hole hidden in the reeds. The impoverished women are waiting for their son/husband Kichi to return from the army, but get unsettling news one day when their starving neighbor Hachi deserts the army after a losing battle and tells them he witnessed Kichi getting killed.

The mother can’t accept this and resents the boorish Hachi for returning alone, and things are further complicated when Hachi lusts after the younger woman and eventually succeeds in luring her to his abode every night for hot sex. The elderly woman complains to him that she will not survive if he takes the young woman away from her, as he plans. When she can’t change Hachi’s mind even after offering herself for sex, she works the girl over with stories about going to purgatory for sinning. This has some effect but doesn’t seem to be working either, but when a noble samurai (Uno) dressed in a frightening demon’s mask stumbles into her hut to ask directions–she lures him into the hole and his death. She then uses the mask to frighten the girl away from her lover.

It’s a harrowing study about the rotten nature of people and the useless wars they always fight that keeps them from being civilized. Erotically presented and visually appealing it sets a chilling mood, where the women live like animals from day to day and the men are either warriors or are caught in the darkness of their lust and greed and violence–every character is a negative. Shindo’s allegory points its finger at how the human condition is spoiled by corruption of its soul and during times of war civilization breaks down–even nature responds by frost in the summer to ruin the crops. The film almost loses itself in the end with too heavy-handed an attempt to show the old lady lost in the darkness of her fears, while she is madly calling out in vain for humanity to return to its senses and show its beauty. But Shindo pulls back with restraint just in the time for Kiyomi Kuroda’s startling black-and-white cinematography to leave you visualizing the surrounding darkness and the fluttering reeds that hide the truths about both the warriors and farmers. Interesting as a claustrophobic vision, but Shindo never goes further in his minimal narrative than setting the viewer up to meditate on the meaning of existence.

REVIEWED ON 4/1/2004 GRADE: B +