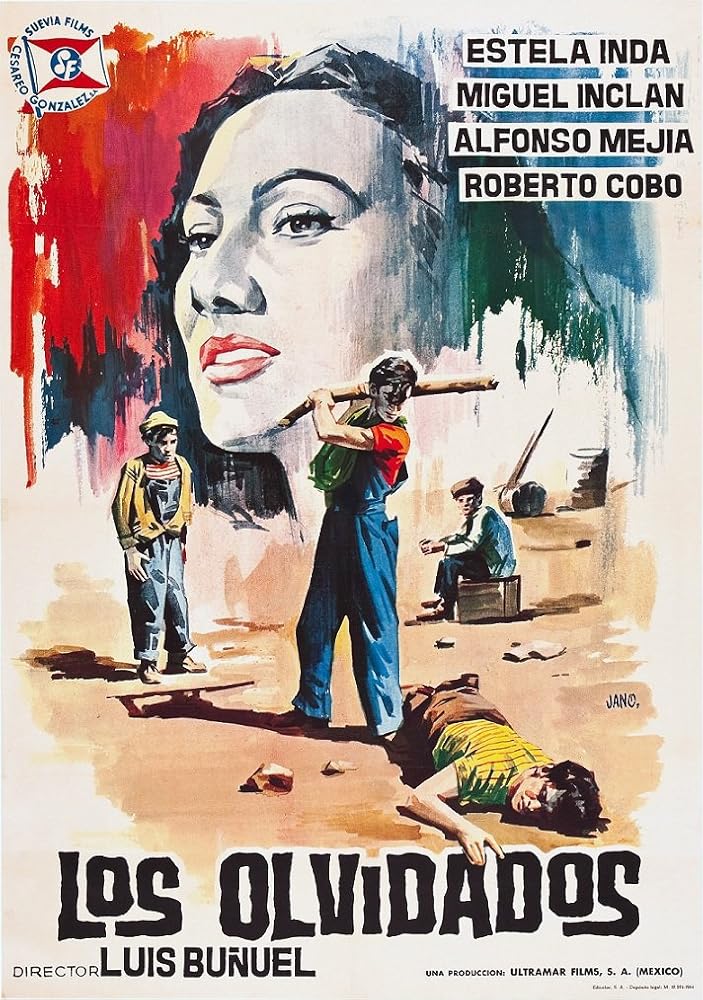

LOS OLVIDADOS (The Forgotten Ones) (The Young and the Damned)

(director/writer: Luis Buñuel; screenwriters: Luis Alcoriza/Oscar Dancigers; cinematographer: Gabriel Figueroa; editor: Carlos Savage; music: Rodolfo Halffter/Gustavo Pittaluga; cast: Alfonso Mejía (Pedro), Estela Inda (Pedro’s Mother), Miguel Inclán (Don Carmelo, the blind man), Roberto Cobo (Jaibo), Alma Delia Fuentes (Meche), Francisco Jambrina (The Principal), Jesús Navarro (Julian’s father), Javier Amézcua (Julian), Mário Ramírez (Big Eyes, the lost boy), Efraín Arauz (Cacarizo), Jorge Pérez (Pelon), Francisco Jambrina (Farm School Director); Runtime: 88; MPAA Rating: NR; producers: Sergio Kogan/Oscar Dancigers/Jaime A. Menasce/Sergio Kogan; Koch Lorber; 1950-Mexico-in Spanish with English subtitles)

“The brilliantly acrimonious film is about connecting poverty with juvenile street crime.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

The Spaniard Luis Buñuel made in 1928 with Salvador Dali a short dream-like avant-garde feature called Un Chien Andalou (noted for its scenes of a sliced eye and crawling ants). In 1930 he made his second feature l’Age d’or, a controversial highly erotic work that offended the Catholic Church. Unable to get funding, his next film Los Olvidados came some twenty years later in Mexico. It’s based on true events about troubled juveniles in the slums of Mexico City. It’s a fair-minded, unsentimental look at a group of juvenile delinquents who live on the streets without any hope. It has two illustrious dream sequences, giving it a surreal look. There are many symbolic points made about milk as the wholesome drink because it connects one with a mother’s nurturing and that having good looking gams might be all that it takes for a female to attract a man. There’s also an unforgettable conclusion about Pedro, a youngster who wanted to be good but his young impoverished mother rejected him and he’s left on his own to live in the streets. After being brutally beaten by his much older gang leader nemesis, Jaibon, for violating the street code of ratting, Pedro’s body is placed in a sack and set on a donkey by his uncaring neighbors and dumped in a garbage heap (symbolic of the capitalist system’s disregard for poverty that allows a human being to be discarded like worthless trash).

The brilliantly acrimonious film is about connecting poverty with juvenile street crime. It earned Buñuel his well-deserved international reputation. By combining Italian neo-realism with Hollywood teen genre films, the gifted director found a way to articulate the anger in the streets from these forgotten youths–supposedly hidden away in every major western city. To Buñuel’s credit he doesn’t lay all the blame on society, but also points his finger at the individual’s failure to act responsibly and the lack of family support.

When Jaibo escapes from reform school, he starts up again a pack of street kids from the ghetto who follow his unwise leadership in robbing a cripple and a blind man. The blind man rightfully hates the gang for being his tormentors and frowns upon the uncaring attitude of the parents, but is not a sympathetic figure because he’s a hypocrite, takes sexual liberties with an under-aged girl and his final solution to the delinquency problem is to have all the slum kids exterminated. Two other street causalities of note are a well-mannered out-of-town boy, nicknamed Big Eyes by the street kids, abandoned by his father who has to learn how to live on the street and a hard-worker named Julian, the family’s breadwinner, who is brutally murdered in a cowardly fashion by Jaibo as an act of revenge for sending him to the can.

The nonprofessional cast make for excellent subjects to study the universal social conditions that lead to street violence.

REVIEWED ON 2/10/2006 GRADE: A+ https://dennisschwartzreviews.com/