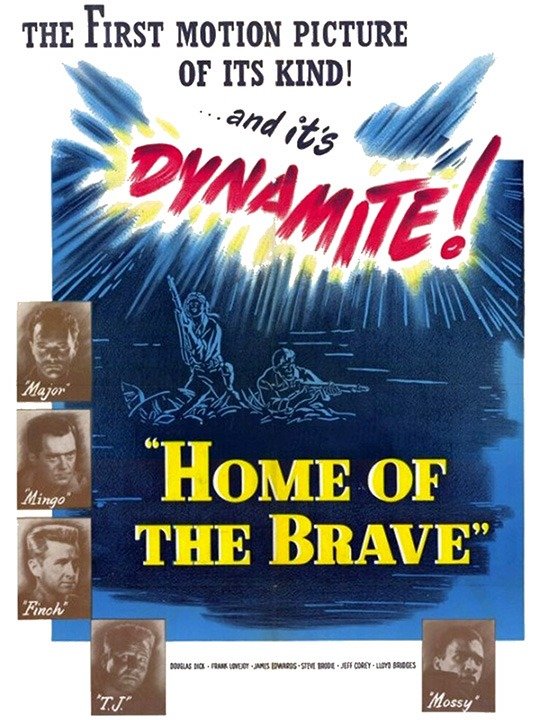

HOME OF THE BRAVE

(director: Mark Robson; screenwriters: Carl Foreman/from the play by Arthur Laurents; cinematographer: Robert De Grasse; editor: Harry Gerstad; music: Dimitri Tiomkin; cast: Douglas Dirk (Major Robinson), Steve Brodie (Corporal T.J. Everett), Jeff Corey (Doctor), Lloyd Bridges (Finch), Frank Lovejoy (Sgt. Mingo), James Edwards (Peter Moss), Cliff Clark (Colonel Baker; Runtime: 88; MPAA Rating: NR; producers: Stanley Kramer/Robert Stillman; Republic Pictures Home Videos; 1949)

“Not without some hard-hitting moments.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Home of the Brave is based on the hit Broadway play by Arthur Laurents; it was written by Carl Foreman and directed by Mark Robson. The play tells of a young Jewish soldier who was the victim of anti-Semitism while serving his country. In the film the then 35-year-old liberal producer Kramer substituted a Negro character for the Jewish victim. At its release date it was viewed as a daring ‘Negro problem picture,’ that intelligently portrayed blacks as concerned over racial issues (no longer in plantation roles as singers and hoofers) and launched Hollywood’s cycle of Negro problem pictures at the end of the 1940s (Pinky, Lost Boundaries, and Intruder in the Dust). It reflected a positive change in attitude towards blacks by Hollywood. But when viewed today, it seems more like a cautionary tale that is as outdated as its flashbacks on a basketball game. That’s not to say its message isn’t on target, wasn’t necessary at the time and not without some hard-hitting moments.

The film opens with a sympathetic army shrink, an unnamed captain (Jeff Corey), in a military hospital during World War II trying to find out the psychological cause of the paralysis of a young Negro private named Peter Moss (James Edwards), who returned from a dangerous five-man voluntary four-day reconnaissance mission on a Japanese-held Pacific island unable to walk for no apparent physical reasons. Through a series of flashbacks Moss answers the captain’s questions as he begins to regain his memory, with the help of drugs, and it’s learned that all through his life he faced prejudice and didn’t know how to deal with it. Moss is a surveyor who joins the team put together by gung-ho 26-year-old Major Robinson (Douglas Dirk) that includes the bigoted Corporal T. J. Everett (Steve Brodie), a cartographer named Finch (Lloyd Bridges) and a disgruntled sergeant named Mingo (Frank Lovejoy). Moss recognizes Finch as an old friend and basketball teammate from their schooldays in Pittsburgh. Robinson is put off that the colonel sent him a colored boy, but when he calls his superior he’s told that he’s to use anyone who can help no matter what color.

We follow the men on their mission as they all satisfactorily carry out their duties to chart the island for a future attack. Moss and Finch become close and during their breaks plan to be partners in opening up a bar after the war. Mingo’s wife writes letters with poetry, such as “My darling, darling, darling, I’ll never again use the word ‘love’ without thinking only of you.” And another that says “Divided we fall, united we stand, coward take my coward’s hand.” But the letter he still can’t forget is the last one that starts out “Dearest, this is the hardest letter I’ve ever had to write.” During the mission Mingo will lose an arm. While bringing back to the base camp the maps Finch retreats when he realizes he lost them in the jungle and when Moss wants them to turn back without them an angry Finch loses himself and calls him a yellow “nigger.” Finch finds the maps but gets hit and Moss returns to cover his friend’s back and insists on staying with him, but Finch orders him to leave with the maps or the mission will fail. Back at the base camp, the men hear the screams of a tortured Finch who was captured by the Japs and feel helpless. After the screaming stops Moss goes back and discovers the dead Finch. That’s when Moss was unable to walk and had to be carried back to the dinghy by T. J.. Though it’s revealed T. J. took pleasure in making racial cracks out in the open, the shrink determines it’s the racist American society as a whole that weighed on the sensitive private’s mind and led to him cracking up. What initiated that severe reaction was the feeling of guilt Moss had that it was Finch who got it instead of him. To save time, the doctor in getting his patient to walk again takes an unorthodox risk and shouts, “Get up, you dirty nigger.” This riles Moss up so much that he struggles to walk across the room to get to the doctor. By the time he reaches the doctor, he realizes the radical treatment worked and he gratefully embraces him. The next day, before being shipped back to the States as a hero with Mingo, Mingo tells him that he would like to become partners with him in the bar business. The fairy-tale optimistic ending signals a time when whites and blacks will bond together in a common cause. The upbeat ending seemed more pleasing than real for that time period, but during the civil rights struggle of the 1960s we did see some of this interracial activity. Surprising to the studios, the film proved to be botha commercial and critical success.

REVIEWED ON 5/20/2006 GRADE: B