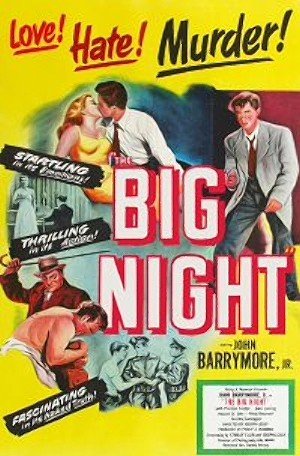

BIG NIGHT, THE

(director/writer: Joseph Losey; screenwriters: Stanley Ellin/from his novel Dreadful Summit by Ellin; cinematographer: Hal Mohr; editor: Edward Mann; music: Lynn Murray; cast: John Barrymore Jr. (George La Main), Preston Foster (Andy La Main), Joan Lorring (Marion Rostina), Howard St. John (Al Judge), Dorothy Comingore (Julie Rostina), Philip Bourneuf (Dr. Cooper), Howland Chamberlain (Flanagan), Myron Healey (Kennealy), Emil Meyer (Peckinpaugh), Mauri Lynn (Singer, Terry Angeleu); Runtime: 75; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Philip A. Waxman; United Artists; 1951)

“An hysterical melodrama posing as a film noir due to the dark underworld it inhabits.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Blacklisted Joseph Losey’s (“The Criminal “/”Accident”/”The Servant”) last film in America before his European exile is an hysterical melodrama posing as a film noir due to the dark underworld it inhabits. It’s based on the novel Dreadful Summit by Stanley Ellin. Losey complained that producer Waxman took out the flashbacks he planned and forced it on the filmmaker as a straight chronological narrative, thereby losing some of its edge. But it really suffers from being too theatrical and having a somewhat pretentious script, as cowritten by Losey and Ellin.

Warning: spoiler in the next paragraph.

Socially awkward, callow and timid teenager George La Main (John Barrymore Jr., son of the great actor) is picked on by his southern California peers for being such a nerd as he comes home from school on Friday. George is excited that on this upcoming big night his rugged widowed bar owner father Andy (Preston Foster) is to celebrate his 17th birthday by taking him to the prize fights. He’s only puzzled why his father’s longtime Polish girlfriend, Frances, is not present, but receives no response when he asks his dad nor from Flanagan (Howland Chamberlain), the loyal bartender and George’s surrogate parent. At the bar, dad surprises George with a birthday cake and has the patrons sing happy birthday. The joy is shortlived, as noted sportswriter, Al Judge (Howard St. John), a cripple, enters the bar and gives Andy a vicious caning without him resisting. The hero worshiping kid is disappointed that his father does nothing. Before going out alone to the fight as his father is put to bed, he takes the gun in the register. At the fight, he scalps his father’s ticket to a talkative, decadent, obnoxious, bibulous professor, Dr. Cooper (Philip Bourneuf), and then loses the money from the sale when low-life scam artist Peckinpaugh (Emil Meyer) pretends to be an undercover cop. Later in a bar near the arena, while accompanied by Cooper, who told him the other guy was a con artist, George spots Judge and waits for him in the men’s room. But Peckinpaugh is there and Judge flees. Upset that Judge escaped George, now having balls because of the gun, savagely turns on the hood and beats the living daylights out of him. Cooper takes him to the Florida Club, a cheap dive where the prof’s lonely girlfriend is a singer, Julie Rostina (Dorothy Comingore), and then to the apartment the singer shares with her sweet sister Marion (Joan Lorring). Cooper tells the kid how to find Judge, and he tracks him down in the apartment building where Frances lives and thereby discovers that Frances is Judge’s sister and has been dead for a week. The kid then confronts Judge and pulls a gun on him, and seems to have accidentally killed him during a tussle.

In the climax everything becomes clear why the father acted like he did, even if the explanation makes you wonder what the father means by love. The revenge drama is viewed as all of the following: a coming-of-age film for George, a comment on how a gun can make someone feel brave, how a lack of communication between parent and child could have deadly consequences and an allegory on America’s repressive society. Every character is used as a symbol: the professor represents intellectual dishonesty; Judge’s name speaks for itself, as someone who thinks he is above the law with his sadistic outburst and his stinging opinions of what’s right or wrong; Marion Rostina is the good girl who tries but fails to save George because others interfere with her; the father is the burly man who weakly submits to punishment from someone who pretends to be his judge and is viewed as a stand-in for an America that gives into red-baiting bullies such as Senator McCarthy; and the wide-eyed innocent George is viewed as America’s last hope to see things clearly, as he’s the confused nice kid who is so alienated that he cannot understand how the world works. George has been nurtured in the isolated world of his father’s friendly neighborhood bar only to find himself forced to grownup when he leaves the familiar bar world he understands best to walk the isolated dark city streets, pass under the shadows of the massive oil tank structures which dwarf his presence, attend a prize fight that leaves him out of his element with so many fans screaming for blood and shady characters who are hustling, sit in dive-like nightclubs and squalid apartments, and visit a noisy press-room where the noise is so great he can’t think clearly any more.

REVIEWED ON 1/28/2007 GRADE: B