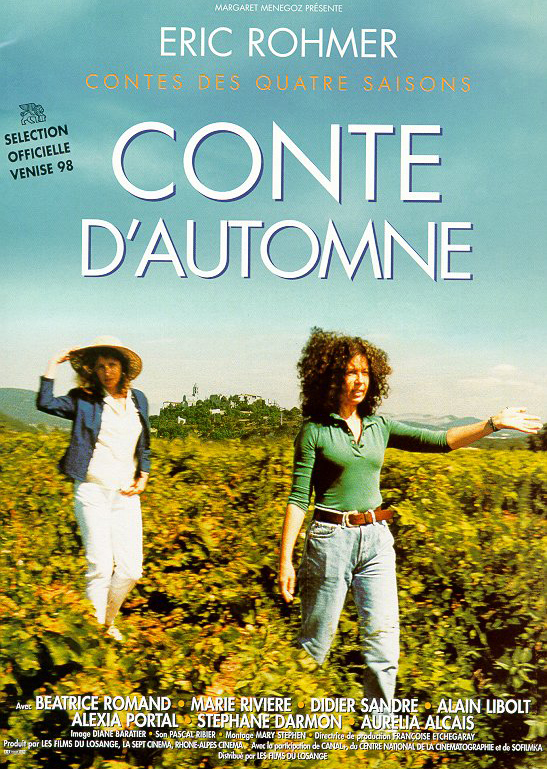

AUTUMN TALE (CONTE D’AUTOMNE)

(director/writer: Eric Rohmer; cinematographer: Diane Baratier; editor: Mary Stephen; cast: Marie Riviere (Isabelle), Beatrice Romand (Magali), Alain Libolt (Gérald), Didier Sandre (Etienne), Alexia Portal (Rosine), Stephane Darmon (Leo), Aurelia Alcais (Emilia ), Matthieu Davette (Grégoire), Yves Alcais (Jean-Jacques); Runtime: 110; October Films; 1998-France)

“This was Rohmer’s fourth and final film about the seasonal cycle and it might be his best one, letting in the most sunlight.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Things in life are not perfect. The beautiful wine growing region of the Rhone Valley in southern France is nearly perfect but it has an eyesore, two smoke stacks from the power plant that smother the natural view. For the 79-year-old Eric Rohmer (My Night at Maud’s/Claire’s Knee/Perceval le Gallois), who spent his career making films in the school of realism, it is the natural things of life that provide him with his sense of wonder and beauty. To prove his point we sit through a lecture on various weeds found where the grapes grow and note how unnecessary it is to spray poison on them and harmfully endanger the grapes growing there, just because some people are put off to look at them if they are messy. For him nature is perfect and only man distorts it, and all he can do as a filmmaker is try to get at that natural beauty without distorting it further. He considers his filmmaking analogous to a religious person worshiping God. You could substitute him with his winemaker in the film and see that for them their work is an art not a business. The heroine makes her wine solely for the connoisseur who recognizes that her local Côte du Rhône is as good as a Gigondas is. So it is with Rohmer, who in actuality might not be such an exacting realist as first thought but more of an artist who happens to be a realist, perhaps, in the mode of a Monet whose artistic work is appreciated because his water lilies mean more to him and should to us than just the flowers they are.

This is a very ordinary love story between middle-aged lonely people who are unable to make a connection with someone else, even though they are people who have a lot to give and are far from being losers. We see how they are unable to be completely happy without someone to love, that their work is only a small consolation for what they are missing. It might take a matchmaker to bring them together, but what will keep them together is the love they have for a moral and physical beauty; that it has to be both that attracts them in order for the romance to be complete. For Rohmer, being moral is simply living as simply as one would: being natural.

Being a French film, it is very chatty. It also takes a long time to develop as it makes sure that we understand all the people involved and what kind of philosophy about life they have, before we come to the crux of the story. How the people speak and how they react to the ordinary things in life, is really what Rohmer is interested in. It is what gives this film its flavor and distinguishes him as a director from other filmmakers of the French New Wave.

To watch a Rohmer film like he intended it to be observed is to take in the magnificence of the natural, whether it is the opening of the film when we are introduced to the town’s older white buildings as the light falls against them and contrasts its whiteness with its black shadows; or, if we view the verdant fall colors of the countryside and its sense of a cultivated peace it conveys as the sun shines on it. This sense of natural beauty has stood the test of time and is worth savoring.

The middle-age winemaker, with the frizzy black hair and alert dark-eyes, is the widowed Magali (Romand), whose grown daughter and college student son live away from her. She confides to her close childhood friend and the town bookseller, Isabelle (Riviere), who visits her vineyard to invite her to her daughter Emilia’s (Alcais) wedding, that she is not interested in having a man because she is too busy with the harvest; but, she also confides to her that she is lonely and could be with the right man if he would just appear. She seems to be disconsolate about her chances of getting the right man saying, “At my age, it’s easier to find buried treasure than a man.” Isabel is struck by her neighbor’s plight and suggests taking out an ad in the paper, but that is soundly rejected by the proud and conservative woman. The happily married Isabel, decides to take the ad out without telling her friend. When she makes contact with the right guy, Gérald (Libolt), she goes out with him three times to make sure that he’s right for her friend. She then surreptitiously invites him to her daughter’s wedding to meet the unsuspecting Magali. At the wedding, she surprises Gérald and tells him that the ad was not for her but for her vintner friend. Of course, she feels good that she can still attract a man and also do this good deed for her friend.

There is one more matchmaker in this film, Rosine (Alexia), a sweet but manipulative college student who is going out with Magali’s son Leo (Darmon), on the rebound, after having a recent affair with her much older philosophy professor, Etienne (Sandre). Rosine loves Leo’s mother but does not love her son to his disappointment, and says she is only seeing Leo so she can continue talking with Magali. She has ended the affair with the professor, insisting on them remaining friends so she can pick up any pearls of wisdom he might throw out as they converse. She seems to love his philosophy more than she loves him. He, of course, can’t keep his hands off her. Rosine, feeling the emptiness in her friend’s life, decides to bring the professor to Emilia’s wedding and introduce him to Magali (figuring this way she can kill two birds with one stone, find him a woman and then she can feel safe to be his friend and in that way she will always have Magali, also, for a friend). She does this after she shows snapshots to each and tells them what she is doing. What distinguishes her matchmaking from Isabelle’s is that she does everything the proper way telling all parties concerned, even Leo. But her matchmaking doesn’t work because there is no chemistry between them.

What is most endearing about the film, even if it is a flighty bourgeois tale, is that it has a French charm to it and a deep-seated respect for all the people involved. That the amorous professor and the playful and impulsive Rosine and the dull Leo are shown in equal terms with the industrious Magali and the elegant Isabelle and the sincere salesman Gérald, which is a sly way of telling the story in a non-judgmental way. There’s much to recommend in this film that feels right and touches a sore subject that should interest mostly those in their later years of life; what the story lacks is a great deal of imagination and a something more substantial to make the modest story have something more to say than it does. The film only goes so far in being realistic before it has to resort to farcical contrivances to keep our interest up. But even if it is not always interesting, it does keep us on our toes rooting for the nice winemaker to come up with something more than a bumper crop.

This was Rohmer’s fourth and final film about the seasonal cycle and it might be his best one, letting in the most sunlight. By the time the film ends we have the feeling that we really know these individuals, it is as if we met them in real life and they have become our acquaintances.

REVIEWED ON 9/5/99 GRADE: B