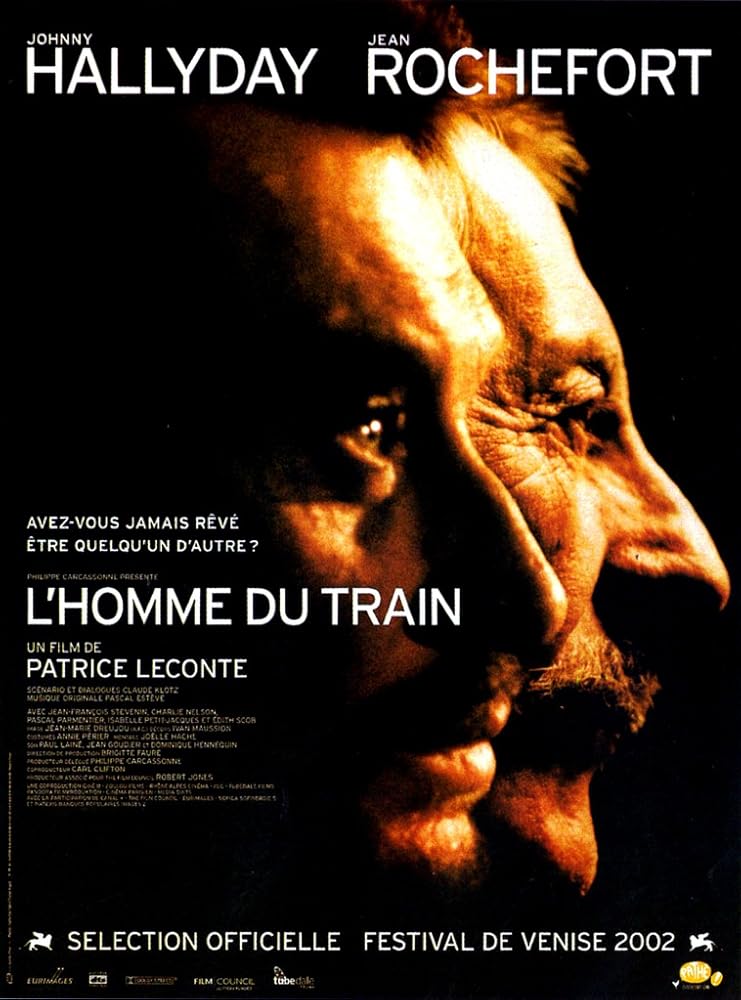

MAN ON THE TRAIN, THE (Homme du train, L’)

(director: Patrice Leconte; screenwriter: Claude Klotz; cinematographer: Jean-Marie Dreujou; editor: Joëlle Hache; music: Pascal Esteve; cast: Jean Rochefort (Monsieur Manesquier), Johnny Hallyday (Milan), Jean-François Stevenin (Luigi), Charlie Nelson (Max), Pascal Parmentier (Sadko), Isabelle Petit-Jacques (Viviane), Edith Scob (Manesquier’s Sister); Runtime: 90; MPAA Rating: R; producer: Philippe Carcassonne; Paramount Classics; 2002-France/United Kingdom/Germany/Japan-in French with English subtitles)

“It all seemed so forgettable like one of those dreams you might have on a suburban train.“

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Patrice Leconte’s (“Widow of Saint-Piere“) 19th feature is a conventional story of an unlikely encounter between two men thrown together by circumstances, each pondering the road not taken and wondering what their life would have been like if they were in the other fellow’s shoes. It’s only the ambiguous ending that force feeds the theme of how these strangers in their few days together changed their way of thinking as the twisty ending, that is subject to one’s own interpretation, tries desperately to save this film by providing it with an edge. But it seems more like a contrivance than a genuine getting to something big to say about lifestyles making the man and how lives can become intertwined through dreams.

Johnny Hallyday (the 59-year-old singer is a rock ‘n’ roll French legend and sometimes actor) is the laconic mysterious tough guy with the face that looks like it has been chiseled in granite. He goes by the name of Milan. The scruffy looking hoodlum type is wearing a fringed black leather jacket and has come by train to a small town in the French Alps in the early evening hours of November to rob a bank with three other companions he’s to meet later. The gruff late middle-aged man proudly states he does not ask questions, and in fact he hardly speaks about anything. Jean Rochefort (the 73-year-old star of many films who sports a similar look to comic Jacques Tati) is the chatty Monsieur Manesquier, an elderly old fashioned retired poetry teacher dressed stylishly in his proper middle-class clothes, who tutors an uninspired boy student in literature just to keep active. He’s a lonely man who never married and lives an uneventful life in his family’s orderly but cramped Victorian-like mansion he inherited from his mother when she passed on several years ago. Though he’s not a man of means, he still lives a secure life in the stately house that is somewhat rundown because of a lack of repairs. His only worries seem to be that he always gets the same haircut and the bakery clerk annoys him by always asking ‘if that will be all’ after a sale, even though he once told her not to ask him that anymore.

By chance the teacher meets Milan in the pharmacy soon after he arrives with a giant headache requiring aspirins, and invites him home to take the soluble tablets with water. The men immediately recognize that they are opposites and envy each other’s life, accepting each for their flaws without being judgmental. Since the only hotel in town is closed for the season, Milan is invited to stay even though Manesquier quickly figures out he’s here to rob the bank. I just wondered why Milan didn’t know the hotel is closed if the one arranging the robbery is a local named Max. Also, it seems unlikely that Milan wasn’t provided with a place to stay, as was the alcoholic trigger man Luigi. The fourth robber is the getaway driver, a wacko named Sadko who speaks only one sentence a day and that before 10 a.m.–which takes the form of a Zen riddle. Going to the robbery on Saturday morning, he says “Time passes for the centuries and for the doves.”

For the rest of the film until the final 5 minutes, these two strangers in their own way spill the beans about their life. Manesquier gives the bank robber a book of poems and a pair of bedroom slippers, the criminal returns the favor by teaching the poetry teacher more or less how to fire a gun and at his request joins him for dinner with Viviane. She’s his mistress, who married another 15 years ago. Nothing much happens, but we learn that Saturday is a big day for both. Milan will rob the bank and Manesquier will get open-heart surgery in the morning at the same time as the heist. Much time is spent showing that Milan is a risk-taker and the cautious Manesquier is a planner. But there was not one thing profound about this opposite’s attract story. What kept it hopping was the filmmaker’s marvelous craftsmanship and the beautiful photography dangled like candy before the viewer’s bitter-sweet tooth. The artsy flavorings did make it an enjoyable watch, no matter how empty it all seemed.

The strictly character-study script by the 70-year-old novelist Claude Klotz, who is a longtime collaborator of Leconte’s, is nothing to write home about and far short of being a thriller as one might expect. If the aim was to keep things elementary as Leconte stated in interviews, then he has succeeded only too well. I couldn’t find much to ponder afterwards, as it all seemed so forgettable like one of those dreams you might have on a suburban commuter train. It’s a film that began with promise about a mysterious encounter and ended without promise in an artful but contrived way that made the story seem irrelevant, as the two world-weary misanthropes at last merged into the same character. Though both men have little to say about the opposite sex except that they make good mothers and are handy to have around when one is in the mood for sex, there is nothing about their heart-to-heart male bonding thing that hints of anything homosexual. These are just two droll men who have stopped living some time ago and don’t know to rekindle their life, except they develop this odd twinge that maybe they can assume the identity of the other and learn to live again. It was all hardly convincing, and not as charming as you might think despite the pleasant performances.

REVIEWED ON 6/25/2003 GRADE: C