K-PAX

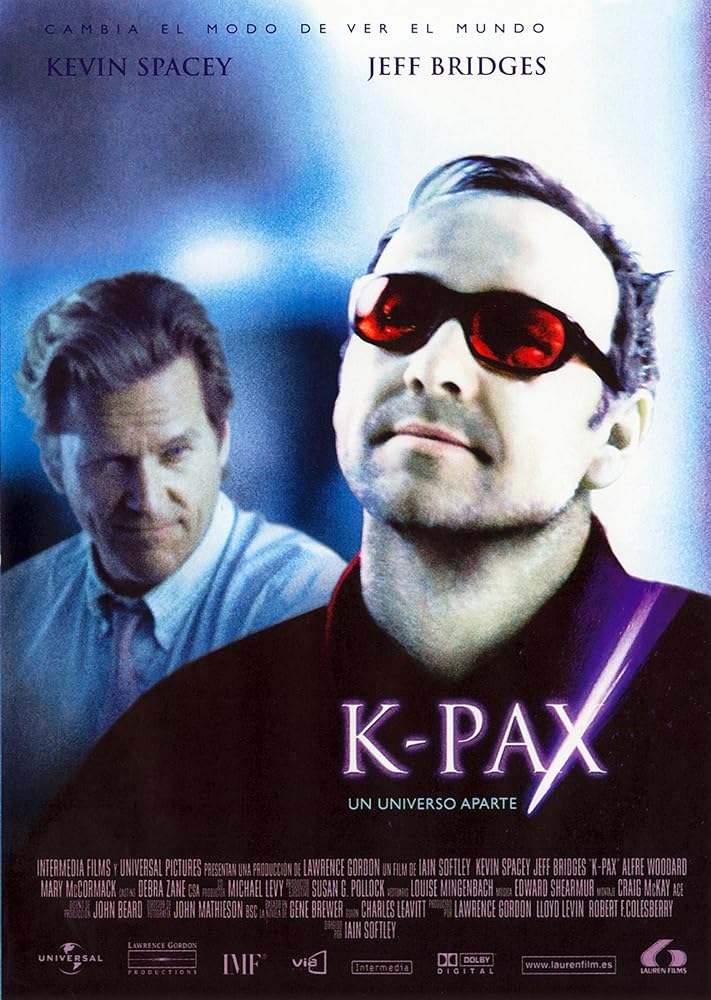

(director/writer: Iain Softley; screenwriters: Charles Leavitt/based on the novel by Gene Brewer; cinematographer: John Mathieson; editor: Craig McKay; music: Edward Shearmur; cast: Kevin Spacey (Prot), Jeff Bridges (Dr. Mark Powell), Alfre Woodard (Claudia), Mary McCormack (Rachel Powell), Peter Gerety (Sal), Saul Williams (Ernie), David Patrick Kelly (Howie), Celia Weston (Mrs. Doris Archer), Melanee Murray (Bess), Kimberly Scott (Joyce), Ajay Naidu (Dr. Chakraborty); Runtime: 118; Universal Pictures; 2001)

“Could never get over the tired script.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

K-Pax is about a genial workaholic shrink at a fancy Manhattan psychiatric hospital, Dr. Mark Powell (Jeff Bridges), treating a highly intellectual and gentle man who calls himself Prot (Kevin Spacey) and insists he comes from an unknown planet called K-Pax. Prot makes his grand entrance in Grand Central Station to the beat of some New Age tunes, where he appears suddenly out of nowhere in the crowded station during the mugging of a woman. Prot’s dressed in dark sun glasses and has a golden aura surrounding him; a panhandler is looking up at him in wonder because the man came from “nowhere” to help the mugging vic. This setup makes him either a mental case or an alien, or perhaps he’s just an eccentric good Samaritan.

Prot is referred by the police to Bellevue for mental observations, then to Dr. Powell’s clinic for a more intensive study. He tells them at the clinic that he’s an alien. That he’s from a planet which is a thousand light years away. Prot shows off his supernatural powers that are far superior morally and intellectually than the ones of earthlings, and he probes with a detached air into human problems and dispenses remedies at will while making a report on his five year visit to Earth. The fun in the story is in pursuing his mysterious origins, but once the film throws light upon the mystery — the story falls into psychobabble.

Prot will by the film’s end miraculously cure at least three severely damaged mental patients (David Patrick Kelly/Saul Williams/Celia Weston) and help others in many smaller ways (Melanee Murray/Peter Gerety), he even solves Dr. Powell’s ticklish family problem by getting him to talk again with his college son from his first wife. For about an hour into the film, Prot is a charmer and keeps this manipulative story mildly entertaining. He tickles his shrink’s curiosity by not reacting metabolically to high dosages of medicines and drugs; by his confident attitude that he’s a time traveler and that he can disappear at will from the secure clinic–he takes a holiday north to Greenland for a few days; he even communicates with a dog by understanding what his barks mean; and, he shows off his superior knowledge of celestial science to a panel of leading astrophysicists, who assemble in the Rose Center planetarium to hear him fill them in on what they don’t know. It reminded me most of the 1986 Argentine film by Eliseo Subiela “Man Facing Southeast.” That film also left the viewer to draw his own conclusions on whether the patient is a nut or an alien visitor, and was also a manipulative film that failed to address the real problems of the mentally ill except to glorify them in unreal general terms.

The film had great performances by both Spacey and Bridges, but their contacts with the mental patients was bogus. It reduced the patients to Hollywood stereotypes of the mentally ill. What it asks from the viewer is a suspension of disbelief as to all the alien jazz it presents, as the seduction of the viewer runs parallel to the shrink being gently taken in by the slight possibility that this one isn’t a loony but a real space visitor. As long as the story kept that plot line going, it had some intrigue. The story was a balancing act of a duel between the sincere but smug Spacey, who could be an alien or someone with a troubled past he deeply repressed, and the plain talking establishment-orientated suburban shrink who was more clever than his simple-minded questioning would indicate.

But the film could never get over the tired script, the familiar story line done in countless mainstream films, and its plodding pace. The second hour of the film was a let down, as the story walked down hospital corridors with dialogue fit only for a B-film. It nauseously ends with a voice-over from Spacey telling the earthlings “Get it right this time. This time is all you have.” Then we are treated to seeing Bridges meet his son for a home visit. The message was too corny for even these fine actors to spit out without looking silly. But it did get in some good licks at conventional psychiatry and their inability to cure or even treat great hordes of patients properly and the modern world’s need to praise Jesus and Buddha but reject their non-violent teachings.

It is based on a novel by Gene Brewer and written by Charles Leavitt, and directed without courage or much imagination by Iain Softley (“Backbeat”/”Hackers”).

REVIEWED ON 11/17/2001 GRADE: C