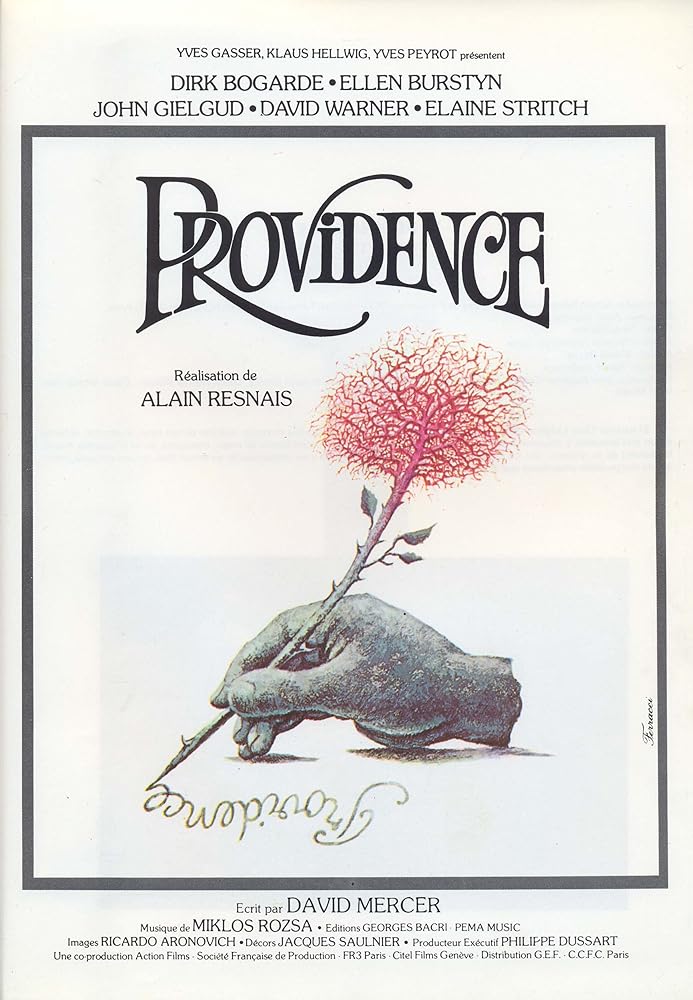

PROVIDENCE

(director: Alain Resnais; screenwriter: David Mercer; cinematographer: Ricardo Aronovitch; editors: Jean-Pierre Besnard/Albert Jurgenson; music: Miklos Rosza; cast: John Gielgud (Clive Langham), Dirk Bogarde (Claud Langham), Ellen Burstyn (Sonia Langham), David Warner (Kevin Woodford), Elaine Stritch (Helen Wiener); Runtime: 105; MPAA Rating: R; producer: Yves Gasser/Klaus Hellwig; RCA/Columbia; 1977-France/Switzerland-in English)

“It’s one of the best films from the 1970s.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

This is idiosyncratic French filmmaker Alain Resnais’s (“Hiroshima Mon Amour”/”Last Year at Marienbad”/ “Muriel”) first English-language film and it finds him at his inventive best; the riveting and insightful pic conforms to his usual surrealistic style and intellectual playfulness, drawing both comedy and relevancy from his stab at probing into how a writer’s mind creates fiction. It’s imaginatively, humorously and cleverly written by playwright David Mercer. The verbose screenplay, that’s brilliantly acted, focuses on Resnais’s usual probing theme involving dreams and memories as blurring reality and fiction. It proves to be a hauntingly dark visionary trip across the landscapes of the unconscious mind; a trip well-worth taking. It’s one of the best films from the 1970s.

Dying elderly British writer Clive Langham (John Gielgud) struggles against rectum pain one night, at his country estate. He’s trying to finish his latest novel, as he uses his family as subjects. Initially things are hard to decipher, as there are confusing scrambled identities such as one character taking on another’s dialogue or persona. Things will become clear by the end, as there’s a story within the story to reckon with that causes this confusion. The novel Clive struggles to write has pugnacious lawyer Claud Langham prosecuting Kevin Woodford, a mild-mannered oddball soldier who while on patrol killed an old man who begged him to put him out of his misery because he was in great pain and was turning into a werewolf. Despite Claud’s attacks on Kevin’s irrational defense, he’s acquitted by the jury that finds him a sympathetic character. This leads to Claud’s sympathetic wife Sonia, disgusted with her hubby’s cold attitude, inviting Kevin to join them for lunch so Claud could apologize. But Claud leaves expressing hatred for Kevin. Later Sonia invites Kevin home and Claud enters while the two are in the bedroom, where Sonia hopes to take the reluctant humanitarian to bed. Claud is unconcerned, and instead picks up his affair with a matronly looking intellectual journalist, Helen Wiener (Elaine Stritch), who looks like his late mother who committed suicide over her terminal cancer condition. The writer gets through the night by boozing it up and his servant finds him asleep on the floor, but washes and dresses him so that in the morning the writer can welcome his immediate family–his happily married son Claud (Dirk Bogarde) and his loyal wife Sonia (Ellen Burstyn), and his bastard scientist son Kevin (David Warner), to celebrate his 78th birthday. As they joyously celebrate together, we see that the amoral writer took liberties with his family members to create a novel that is plunging into Freudian depths.

The film can only be viewed through letting go of your usual linear cinema viewing habits and using your imagination to catch some of the many fascinating enigmas posed; it’s immensely enjoyable for its rich lyrical qualities, the powerful performance of Gielgud, the chic background scenery in the house scenes and its artful achievement as a fine example of pure cinema.

REVIEWED ON 8/16/2007 GRADE: A