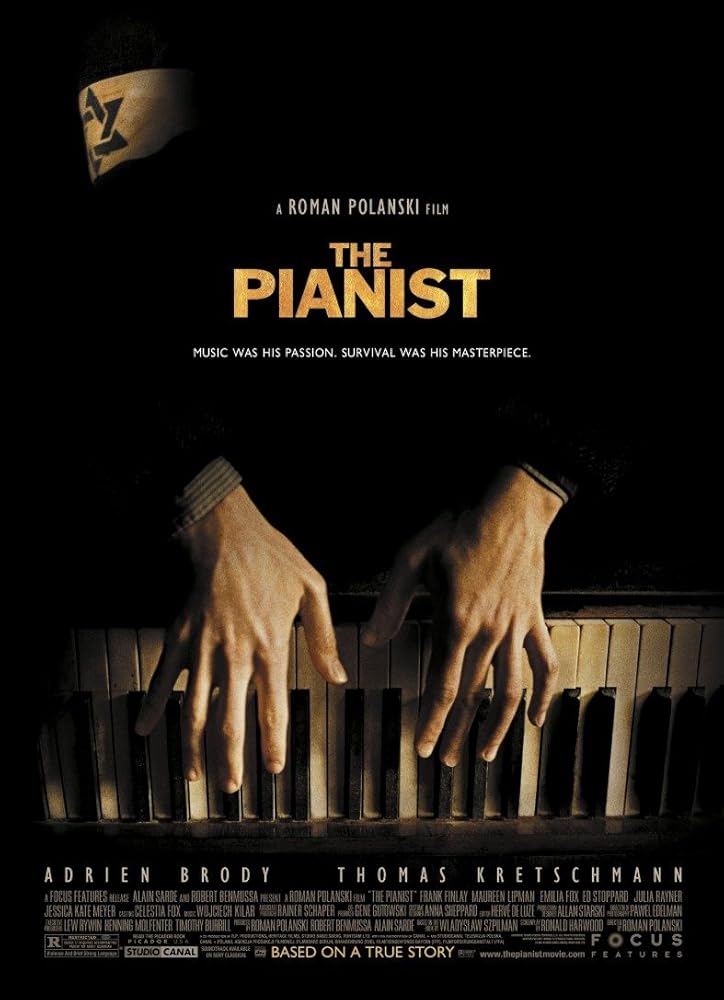

PIANIST, THE

(director: Roman Polanski; screenwriters: Ronald Harwood/from the autobiography by Wladyslaw Szpilman; cinematographer: Pawel Edelman; editor: Herve de Luze; music: Wojciech Kilar; cast: Adrien Brody (Wladyslaw Szpilman), Thomas Kretschmann (Captain Wilm Hosenfeld), Daniel Caltagirone (Majorek), Frank Finlay (The Father), Maureen Lipman (The Mother), Emilia Fox (Dorota), Paul Bradley (Yehuda), Ed Stoppard (Henryk); Runtime: 148; MPAA Rating: R; producers: Robert Benmussa/Alain Sarde/Roman Polanski; Focus Feature Films; 2002- UK/ France/Germany /Poland /Netherlands)

“There is no denying the power of Polanski’s film…”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

“The Pianist” is one of those important films about the Holocaust that is necessary to be filmed from time to time so that the horrors of it will remain fresh in the world’s mind. Though, in all probability such films are mostly preaching to the choir. As entertainment it’s admittedly heavy going and one can easily argue that the human misery of that event has been well covered and documented by so many such Holocaust sub-genre films that there’s no need for another. One can point to the definitive 1985 work by Claude Lanzmann, “Shoah,” arguably the best Holocaust film ever made, and claim enough is enough. Nevertheless, “The Pianist” is such a delicate depiction of world history as viewed from a dramatic personal point of view, that it seems fresh even if it isn’t quite so fresh. The film becomes enlivened as a character study of someone faced with a nightmare scenario of his world collapsing before him while he’s helpless to do anything but fight for survival and dignity, as he’s trapped like a wounded animal who happens to be witnessing the destruction of civilization as he knew it. That’s a subject both Jew and gentile can relate to and despite all such trepidations one might have about wading through such heavy material, the film results in a realistic and eye-opening look at the Holocaust that refuses to flinch at how low humanity sunk and is just as unflinching in its belief in how resilient the human spirit is. The film is so wonderfully enriched by its conventional way of shooting and also by its unconventional way of not relying on such conventional devices to get its story across, that it makes a deep impression on the sensitivity of the viewer. It strikes a balance between the human spirit acting out of kindness and the senseless brutality of the Nazis, so much so that it fuses into a strange work of raw beauty. Cinematographer Pawel Edelman deserves a lion’s share of the credit for that startling look. Roman Polanski, himself a Holocaust survivor from Poland, is more than capable of making such a true story about his fellow Polish Holocaust survivor, the composer and pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman, into such a captivating and moving film. This is especially so because he felt this tragedy himself through his first-hand experience. When Polanski was eight his parents were taken from their Cracow home to a Nazi concentration camp, where his mother died. He escaped from the Cracow ghetto just before it was liquidated and wandered about the Polish countryside seeking refuge with a succession of Catholic families. He witnessed the sadistic games played by several German soldiers, just like the incidents that occured throughout the film. These terrible memories never left him and now he has a chance to share it with the public through this film (there was also a book about some of his life experiences called “The Painted Bird” by Jerzy Kosinski). There is no denying the power of Polanski’s film, its heartfelt anguish, and its brilliant manner of bringing the story out so that it becomes penetrating in a way that goes beyond the shock of such atrocities. That is something only a very few films, the great ones, can attest to reaching.

The story opens in 1939 and Warsaw is being bombed during the German invasion as the pianist, Wladyslaw Szpilman (Adrian Brody), finishes playing Chopin for his radio recital as the station is destroyed by the bombs. He then meets outside the station an attractive cello player, Dorita (Emilia Fox), whom he flirts with in the midst of this catastrophe. Soon after the British and French declare war on Hitler, the Nazis take control of the country and immediately put their “final solution” plans in place against the Jews. Wladyslaw is a young concert pianist, considered the best in Poland, who still lives at home with his middle-class family consisting of his dignified mother (Lipman) and kindly father (Finlay) and his tempestuous brother (Stoppard) and the sister he never got to know as much as he wanted to. He watches in despair as life for the Jew turns from bad to worse. Soldiers humiliate the Jews in the street and beat them whenever they wish to, all Jews have to wear a Star of David armband on the street, an elderly wheelchair-bound man is thrown out of his multi-storied apartment window by the Nazis because he couldn’t stand up for them when they entered his apartment, soldiers randomly shoot Jews in the street, Jews are forbidden entry to the parks, Jews are only allowed to keep a small amount of money, the Nazis regularly loot their homes, and finally the Jews are forced to live in the Warsaw ghetto. The film never asks why the Jews were so obedient or why some Jews became willing collaborators of the Nazis by becoming auxiliary police working to keep their fellow Jews in line in a roughshod manner, as it instead paints an overall ugly picture of what happened without dwelling on the violence of the bodies piling up. It touches on the Warsaw uprising when a group of Jews did fight back but got eliminated. But it saves its most lyrical story for the tale of Wladyslaw and how by a trick of fate he got separated from his family as they were heading by train toward the Treblinka concentration camp. He survived for two-and-a-half years in the Nazi-controlled Warsaw by living in many different safe hideouts and abandoned buildings with the sometime help of contacts he was provided by the Polish Underground–who had various reasons for helping and not all were good ones. Though contrary to what other survivors said about the Poles and their noted anti-Semitism, here they are shown to be mostly helpful to the Jews. Wladyslaw was left in an almost helpless situation when the city becomes almost completely in ruins and he’s left to fend for himself by scrounging around for food while waiting for the Russians to come across the river and free Poland. In one of the last scenes he hides in an attic of a German officer (Kretschmann), and when caught has to play the piano for him. This personal concert is enough to save him, and the irony is that Wladyslaw survives and lives until 2000 when he’s 88 while the German dies in 1952 in a Russian PoW camp.

Brody’s subtle performance requiring little dialogue but much restraint is distinguished by his honest effort and lack of sentimentality; it was the best performance I saw this year. One has the feeling after watching the emaciated pianist hunker down, that he’s the last civilized person left on the planet. The film had a stunning visual sense of the isolation and human depravity that were linked together with the pianist’s pervasive mood of hopelessness. In the film’s last shot, Wladyslaw is accorded an ovation by the Polish people after his Chopin piano recital (the same one that opened the film). It took the film a long time to get to that point (148 minutes), but in an absurdly odd way I began to feel what the pianist was going through and how his music was the only sustaining force that kept him sane in such terrible times. The film felt like a grind, but I don’t mean that as necessarily a bad thing as much as I mean that it provoked thought and penetrated inside one’s own sense of human values and was more of an educational experience than anything else. For those who venture to see such a demanding work, the reward could be an unforgettable experience that allows you to see something else about the Holocaust just when you thought you saw it all. It received the Palme d’Or at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.

REVIEWED ON 12/16/2002 GRADE: A