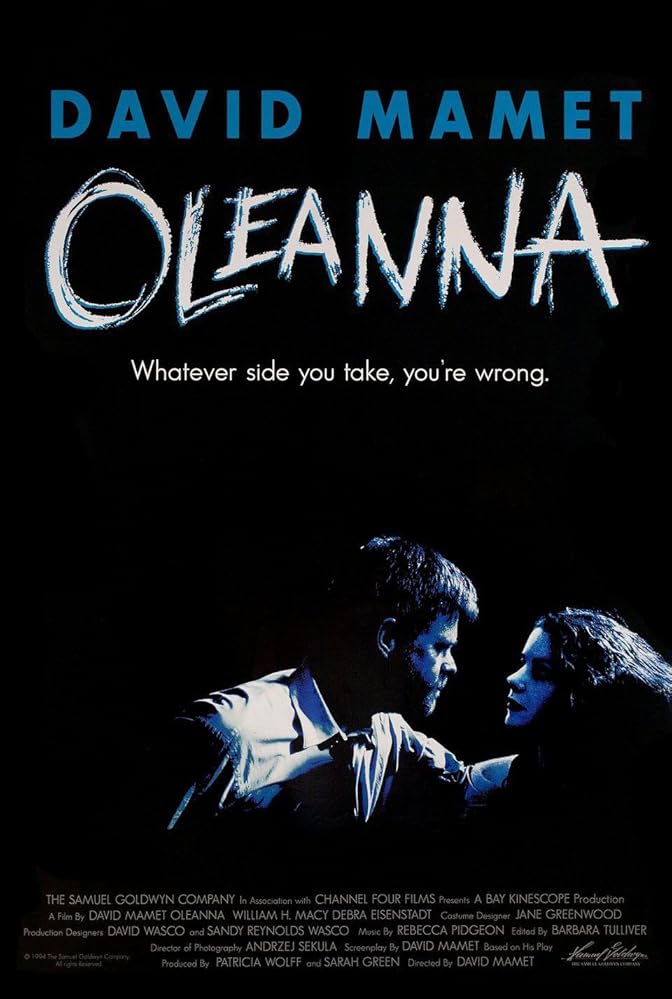

OLEANNA

(director/writer: David Mamet; screenwriter: based on the play by David Mamet; cinematographer: Andrezej Sekula; editor: Barbara Tulliver; music: Rebecca Pidgeon; cast: William H. Macy (John), Debra Eisenstadt (Carol); Runtime: 89; MPAA Rating: R; producers: Patricia Wolff/Sarah Green; MGM Home Entertainment; 1994-USA/UK)

“As to be expected, the Mamet-speak is sharp, witty and masterful.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

David Mamet’s psychological drama is based on his controversial two-character 1992 play set in an unnamed Ivy League college. The two characters are a male college professor named John (William H. Macy) and his female student named Carol (Debra Eisenstadt). John’s married, middle-aged, pompous, self-absorbed, argumentative, and preoccupied with buying his long awaited dream house and being up for tenure. Carol is a flustered student who comes by his office after class to ask for help because she’s failing his course. John does not listen to her pleas for help and instead goes off on a tangent lecturing her in a paternal way on his philosophies about education. He inadvertently touches her shoulder, foolishly tells her an off-color story and proposes that they meet again in private to see if they can possibly change her grade.The professor’s responses do not satisfy the timid Carol but she nevertheless departs without firing back her opinions. Several days later, on their next meeting, Carol announces that on the advice of her “group” she is filing a sexual harassment suit with the faculty committee that has provisionally granted him tenure, also charging John with elitism and telling pornographic tales. Her suit if successful, could cost John his job.

The issue raised is on the whole about the male/female relationship concerning elitism, authority and power in the common everyday experiences of the workplace. Mamet tries to orchestrate an even playing field for the ensuing argument, but many critics of the film feel that he favors the professor’s side because he’s about to lose his job for political reasons. I believe Mamet did a fair job in covering all angles–the student was protesting as she has the right to, especially, when she believes in her heart that she’s right, while the professor feels unduly pressured by a new social order he hasn’t quite adjusted to as of yet. The real thrust of Mamet’s argument might be that education is being reduced to a question of “political correctness,” which both sides use to their advantage to gain favors with the educational institution.

It features scathing performances and provocative dialogue tossed around between the initially arrogant professor and his suddenly empowered feminist student. They both tell their sides of the story with fervor, but are unable to communicate with each other. By act two, the professor loses his bluster and becomes more defensive as the student gains confidence. Their exchange covers many educational themes such as: tenure, curriculum, modern education, and sexual harassment. The teacher-student problems are ably articulated by both characters, but the answers lie with the audience. As to be expected, the Mamet-speak is sharp, witty and masterful. The film’s obscure title, Oleanna, interestingly enough, is taken from a folk tale of a husband (Ole) and wife (Anna) selling worthless swampland to farmers investing their lives’ savings and then disappearing with all the farmer’s money. This became known as the “Oleanna swindle.” Mamet relates that swindle with today’s higher education.

REVIEWED ON 5/24/2004 GRADE: B