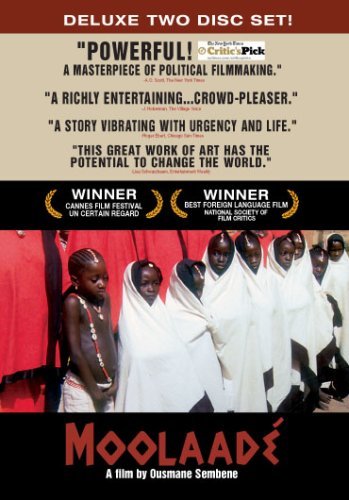

MOOLAADE

(director/writer: Ousmane Sembene; cinematographer: Dominique Gentil; editor: Abdellatif Raïss; music: Boncana Maïga; cast: Fatoumata Coulibaly (Collé Ardo Gallo Sy), Maïmouna Hélène Diarra (Hadjatou), Salimata Traoré (Amasatou), Dominique T. Zeïda (Mercenary), Mah Compaoré (Doyenne), Aminata Dao (Alima Ba), Rasmane Ouedraogo (Collé’s husband); Runtime: 124; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Ousmane Sembene; New Yorker Films; 2004-Senegal/France-in Jula with English subtitles)

“Every character is a symbol for Sembene to realize his humanistic visions in a folklore type of cinema.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

This is noted novelist, Marxist and Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene’s ninth feature, one he made at age 81. Sembene is considered ‘the father of African film.’ He was the first black African to gain international recognition as a filmmaker. This film, the one he considers the most African of any film he has made, is the second part of his trilogy on modern political issues; the first in 2000 was called Faat Kiné (telling about social and economic change in Senegalese society from its colonialist past as seen through the eyes of women), with the third one not made but reportedly about political corruption. Moolaadé is a none too subtle parable that plays as a sharp attack on the abusive patriarchal system; it offers a relentless didactic argument against female genital mutilation told through a fictional story of a courageous woman named Collé in a rural Moslem Senegalese village who takes a stand against the practice. This barbaric practice of the removal of the clitoris dates back to the time of the Greek Herodotus and was a ritual used to subject the females to the ruling males in pre-Islamic times. That this practice continues in Africa and nowhere else in the Moslem world, has drawn the wrath of the filmmaker who hopes to change such a demeaning and unhealthy practice that is responsible for either killing or maiming many of the young females who get cut by the knife.

The film opens with six young girls running away from the Purification (female circumcision), with four frightened girls entering the dusty unnamed Moslem village filled with traditional African mudhuts and a unique mosque that has on its roof an ostrich egg. The girls seek moolaadé (sanctuary or protection) with Collé, a village resident who refused to have her daughter Amsatou cut because her other daughter died from the painful procedure. As is the primitive tribal custom, Collé, the second (and favorite) wife of a tribal council elder’s three wives, offers the girls sanctuary in her home (which means no harm can come to them because a spell has been cast and those who harm the girls will be revenged). Females who do not undergo Purification are called bilakoros, and the pious men say they will not marry them. The tribal elders spurred on by Collé’s husband’s elder brother collect the battery-run radios from the women, which is their only contact with the outside world and the knowledge they gain gives them their only power. In order to get the spell broken, the reluctant husband follows his elder brother’s advice and flogs his wife in public so she would utter the one magical word that can break the spell. When she refuses to relent, the village women come to her aid and rebel against their male masters and in a feel-good ending put a stop to the torturous practice. The narrative also follows a recently returned French immigrant who was supposed to marry Amsatou but is told by his chieftain father he can’t marry a bilakoro; he reacquaints himself with such a simplistic and primitive life, and must decide whether to be modern and rebel against his father or rooted in the past like his father. The only other male who shows some spunk is named Mercenaire, an engaging traveling salesman (selling clothing, condoms, batteries, razors and sneakers) who overcharges and is a womanizer but has a heart. His enterprising capitalism though not without its faults nevertheless proves to offer more hope for the ladies than what the tribal elders have to offer, who are content with their ignorance, prejudices and lack of knowledge. They want only to hold onto their power and are capable of murdering anyone who tries to take that away from them.

Every character is a symbol for Sembene to realize his humanistic visions in a folklore type of cinema; the filmmaker is not afraid to show the ugly side to traditional life, to unabashedly take the feminist viewpoint and to heap derision on the clerics without caring how much he offends. Though his message is delivered in a heavy-handed manner, it’s never without humor, deep conviction and a raw power that signals an urgency for change. Sembene views his Africa at the crossroads of cultural isolation and globalization, and firmly believes the modern way has more to offer than the past even if it’s only televisions or a peddler’s wares.

REVIEWED ON 3/7/2006 GRADE: B https://dennisschwartzreviews.com/