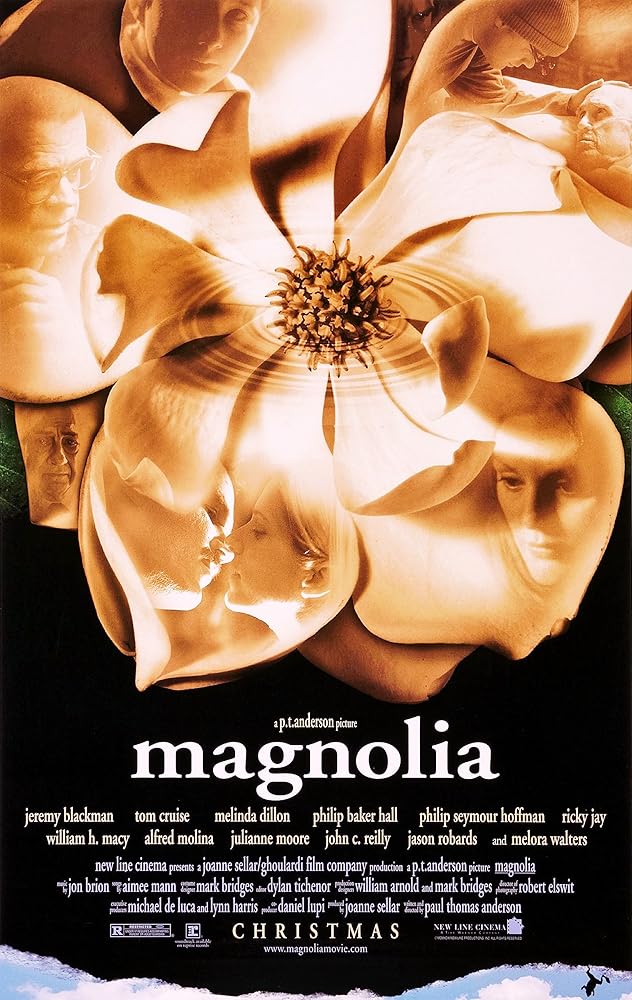

MAGNOLIA

(director/writer: Paul Thomas Anderson; cinematographer: Robert Elswit; editor: Dylan Tichenor; cast: Jeremy Blackman (Stanley Spector), Tom Cruise (Frank T. J. Mackey), Melinda Dillon (Rose Gator), April Grace (Gwenovier, reporter), Luis Guzman (Luis), Philip Baker Hall (Jimmy Gator), Philip Seymour Hoffman (Phil Parma), Ricky Jay (Burt Ramsey), Orlando Jones (Worm), William H. Macy (Donnie Smith, quiz kid), Alfred Molina (Solomon Solomon), Julianne Moore (Linda Partridge), John C. Reilly (Jim Kurring), Jason Robards (Earl Partridge), Melora Walters (Claudia Wilson Gator), Michael Bowen (Stanley’s father); Runtime: 188; New Line Cinema; 1999)

“The title of the film comes from the name on the L.A. street sign.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

This is a wonderfully chaotic work, meriting high praise for what it tried to do and not condemnation for what it failed to do. There’s such a thing as something being spoiled because it has too many good things going for it. That is the case with this ensemble dramatic piece, whose most telling fault is that it eventually resembles an overblown soap opera. Its three hour length and many subplots will attest to that, even though it is artfully woven together. It could in all honesty have enough material for five other movies within it. Therefore it is not surprising that the ingenuously talented director, the 29-year-old Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights/Hard Eight), had to finally tie-up all the loose ends of the story into a nice knot, which resulted in an absurd ending that won’t please too many. But I found myself accepting of its biblical ending and was impressed by the overall results of the film, one that is pumped with self-confidence and a virtuoso style. A work that mirrors greatness, even if it doesn’t quite keep that greatness in proper focus.

The only thing that could save the movie from never ending, is a biblical miracle. It settles for a plague, seemingly right out of the Exodus. That improbable ending was set-up and apologized for in its prologue by the offscreen narrator, who explained three different bizarre chance happenings as unlikely but possible. After all how absurd could that ending be, if the Bible used the same type of material! In one of those prologue pieces a London druggist, in 1911, named Greenberryhill, gets killed by three drifters named, Green, Berry, and Hill.

The reward the viewer gets for sitting through the confusing film, that tries to picture life as a matter of coincidences, is how brilliant the individual skits were and how fine the acting. The cast of Anderson regulars: Philip Baker Hall, Philip Seymour Hoffman, William H. Macy, Julianne Moore, and John C. Reilly, all are larger than life figures. To see Jason Robards as a dying old crotchety TV mogul, with a tube up his nose, made for some effective dramatics. Even Tom Cruise, as Robards’ estranged son, playing an obnoxious hustling infomercials maker for the product he is selling to men so that they can conquer women, was done with a blend of humor and pathos making his role less obnoxious than it could have been. His role reminded me of Jean-Pierre Leaud’ outlandish one in “Irma Vep.” Here Cruise goes for the jugular as a boorish male predator, someone who is just plain unlikable and prone to going off on rants. What Cruise does, is parody himself and other box-office stars with big egos. Cruise deserves much praise for this supporting role.

This is a Los Angeles based film about the causalities of modernism, each character lost in their own shame and failure to be loved. Each life is depicted as being that of a victim, who has been affected by the mass culture of the TV and popular musical worlds and crippled psychologically by such after-effects. They are all-tied together too neatly and the outcome of their sufferings is too predictable for my taste. But that can’t begin to explain how penetrating a human drama this is and how acutely aware the young director is of the people’s misery and heartaches he highlights. This is a derivative film, a homage to Robert Altman’s Short Cuts/Nashville films. But Anderson offers more meat in his character’s parts than did Altman and more finesse in telling his story, allowing his actors to expand their roles more.

The film involves the lives of these nine characters during one rainy day in Southern California. They are each connected because of the following reasons: something happened in their past that stunted their growth, by their family relationships, and by mere coincidence. And, even though all their lives don’t intersect, they are all fighting the same battle to have a clean slate, whether they realize it or not. There is a sensitive but unappreciated cop, who wants to be of help to others, James (John C. Reilly); his coke-using junkie date, resentful of her abusive father, (Melora Walters); her kid game-show host, bastard of a father (Philip Baker Hall), who has learned that he has an incurable cancer and wants to make amends for his past sins; and, Hall’ current whiz kid star, the unhappy genius, Stanley (Jeremy Blackman), who is bullied by his father; there is the former whiz kid, now a pathetic grown-up with problems over his homosexual love life and his failure to be financially successful, Donnie Smith (William H. Macy ). There’s also the game show’s wealthy producer, Earl Partridge (Jason Robards), who lies in pain as he is dying, requesting only to speak to his estranged son, Frank T. J. Mackey (Tom Cruise), who won’t talk to him. Robards also has a gorgeous, younger, unfaithful wife he married when he left his cancer-striken first-wife, the now hysterical and remorseful Linda (Julianne Moore). Earl’s son was 14-years-old when he abandoned his cancer-stricken mother and she died soon afterwards, leaving the TV pitchman Cruise full of self-denial and self-hatred about his past; and finally, there is the home care nurse, Phil Parma (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who is dedicated to looking out for Mr. Partridge.

The performances by all were superb, but Reilly’s and Hoffman’s were better than superb, in a film that didn’t have a featured player. Anderson was able to create a somewhat seamless work out of these separate skits, making use of different camera angles, using TV inter-cutting methods, fast-cut editing, and utilizing a provocative visual style. He also made the story seem fresh and moving in many different directions to catch all the personalities involved.

Anderson made good use of the film’s theme song, through the performance of Aimee Mann. She is heard first by one character then another, until all the film’s troubled souls are brought together by a single refrain. “It’s not … going to stop,” as each one sings, as if signaling the approach of some impending doom.

Whatever fault one might find with the film, that fault is countered by how interesting and refreshing it felt. The magic happening onscreen was in the vibrant telling tragedies of the lost souls and their injured psyches, causalities that are inevitable in America’s modern world of consumerism. The cry for love can be heard on the lips of the two philandering fathers and on all the other lost souls, each searching for a place to fit in and for a way to love someone and be loved in return.

Incidentally, the title of the film comes from the name on the L.A. street sign.

REVIEWED ON 1/28/2000 GRADE: A-