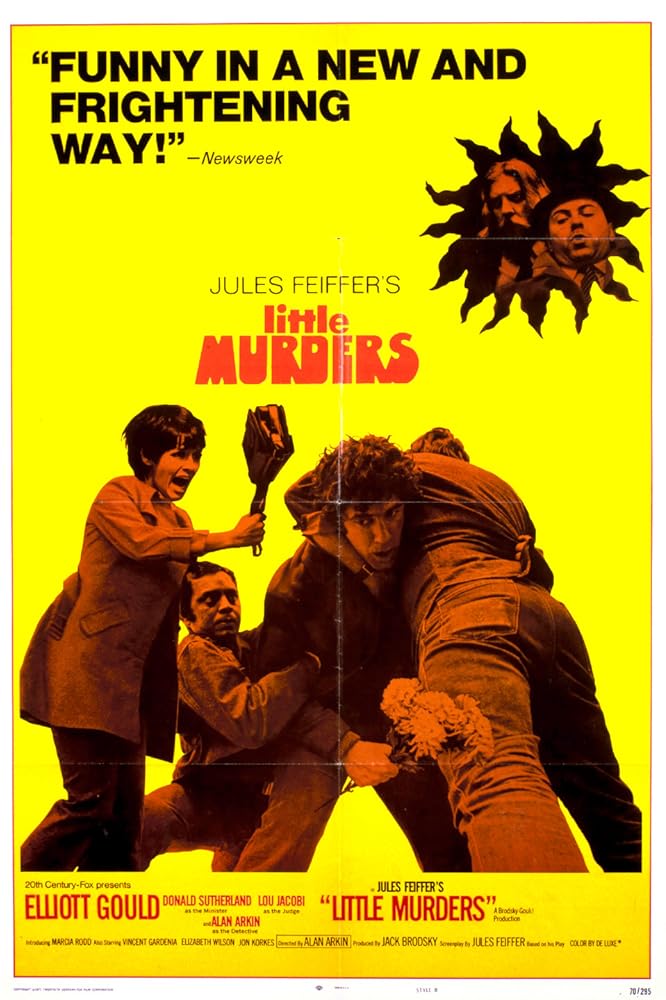

LITTLE MURDERS

(director: Alan Arkin; screenwriter: Jules Feiffer; cinematographer: Gordon Willis; editor: Howard Kuperman; cast: Elliott Gould (Alfred Chamberlain), Marcia Rodd (Patsy Newquist), Vincent Gardenia (Mr. Newquist), Jon Korkes (Kenny Newquist), Elizabeth Wilson (Mrs. Newquist), Donald Sutherland (Minister), Lou Jacobi (Judge Stern), Alan Arkin (Lieutenant Practice), John Randolph (Mr. Chamberlain), Doris Roberts (Mrs. Chamberlain); Runtime: 110; 20th Century-Fox; 1971)

“The black comedy was torridly on target and eerily funny…”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A provocatively caustic, funny, black humor satire on how depressive life has become in the New York City of the late 1960s for the middle-class, who are caught in the changing times. Their family values, belief in God and country, and increasing dependence on TV for news and entertainment has them reeling. The society they know is breaking down. In a city faced with an increase in violent crime, racial hatred, burglaries, garbage strikes, alienation, nuisance phone calls, power outages, muggings, and a controversial Mayor Lindsay; life has become so unbearable that people have come to accept crime as the natural way of life. This acerbic script comes by way of Jules Feiffer, the cartoonist for the Village Voice, who first had this work play off-Broadway at Circle in the Square where it became a hit with the New York theater audience. The author takes delight in dissing such establishment figures as the police, the clergy, and the judges. Vincent Gardenia and Elliott Gould who are in the film, were also in the original play.

The city residents have multiple locks on their doors, the cops are either corrupt or incompetent, and the cries of resignation heard from those who feel beaten down emotionally and physically are as everyday as traffic jams during rush hour.

Alfred Chamberlain (Gould) is an apathetic photographer getting beat up by a gang of kids without trying to defend himself, as he reasons they will soon get tired of punching me. From her apartment window, Patsy Newquist (Marcia), a successful interior decorator who says she wakes up every morning with a smile on her face even when picking up the phone to a heavy breather, observes this mugging and rushes down to rescue the victim. He just walks away without thanking her and when she confronts him, he says he is indifferent to the pain. So starts their troublesome romance as this intelligent, vibrant, and beautiful 27-year-old, thinks she has found her Prince Charming: someone she can mold into her ideal mate.

Everything is played out as a scathing farce. Patsy brings him to meet the family, where the sardonic dad (Gardenia) is despondently ranting about how things have changed for the worse. He is sure that his daughter’s date will be a swish; while Patsy’s mother (Wilson) is in the Pollyanna mode trying to make everything seem sweet while speaking in clichés. When the power goes off, she remarks: “It’s better to strike a match than curse the darkness.” The younger brother is a closet homosexual, disconnected with reality, reading inane books such as “Lesbians in Venus.”

Alfred has become so disillusioned that he has given up taking photographs of people, further disillusioned that commercialization has trivialized the art scene. He discovered that since he developed a reputation he can photograph anything and have it accepted by the Establishment. He now shoots pictures of shit only and Harper’s Bazaar is using it for its next issue. That he is successful, is all that matters to Patsy’s parents in accepting him for their daughter.

In another hilarious scene, Alfred refuses to get married by a judge (Jacobi) who raves like a lunatic about how God helped him get to the high position he now has. Instead, he goes to the hippie Ethical Culture minister (Sutherland) and asks him to officiate at the wedding ceremony. In a funny monologue Sutherland calls the wedding ceremony a search for truth, finding rationals for whatever happens in life, telling the couple that of the 200 marriages he has performed — only 7 are still married. He takes the $250 that Mr. Newquist gave him to include God in the ceremony but tells him it is OK that you gave me the money for that, but it is also OK that I betray you by not including it in the ceremony.

As soon as Patsy injects life into the hapless photographer and has him look back with regret at his early years that made him so filled with angst, she is killed by a sniper in their apartment. In the final scene, Alfred returns to live with Patsy’s family and realizes that the only way to live in an insane world is to be just as crazy as the world is. When he brings back a rifle to the apartment, he brings the family close together again making them happy as they fire out the window of their apartment randomly killing those in the street. Alfred even gets a chance to kill the hostile paranoid cop (Arkin), who tried to intimidate him. This comes at a time when there is a crime wave, where there are 345 unsolved murders in the last 6 months. But, clearly, Feiffer is saying that the little murders occurring daily are the ones we do emotionally to our souls, where we kill our feeling for life by becoming indifferent to the ills of the world.

The performers were outstanding, as I was especially pleased with Marcia Rodd’s captivating portrayal of someone with spunk. The black comedy was torridly on target and eerily funny, but it also seemed to create such a far-out situation that it was difficult to keep laughing when there was so much cynicism and so much that went beyond the farce and became too arcane to decipher where it was leading to. Elizabeth Wilson has the film’s last word and says: “You don’t know how good it is to hear my family laughing again.” This coming after they acted as snipers.

REVIEWED ON 9/4/2000 GRADE: B