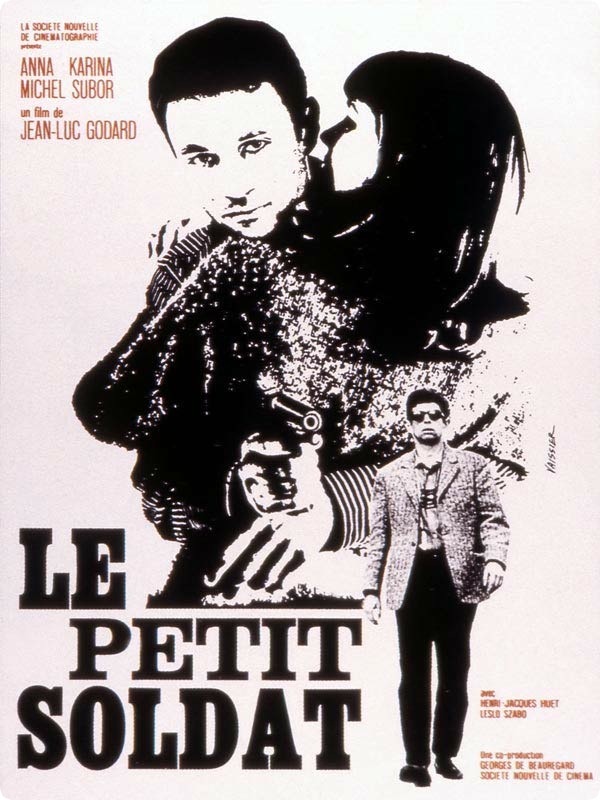

LE PETIT SOLDAT (THE LITTLE SOLDIER)

(director/writer: Jean-Luc Godard; cinematographer: Raoul Coutard; editors: Agnès Guillemot/Nadine Marquand; cast: Michel Subor (Bruno Forestier), Anna Karina (Veronica Dreyer), Henri-Jacques Huet (Jacques), Paul Beauvais (Paul), Laszlo Szabo (Laszlo), Georges de Beauregard (Activist Leader-he’s also the film’s producer); Runtime: 88; Janus; 1963-France)

“Godard is most clear in showing that the Left and Right are two sides of the same coin.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

The first thing you should be aware of about this controversial 1960 political film, shot in B&W by Godard’s favorite cinematographer Raoul Coutard, is that it was not shown until 1963 as it had scenes in it that involved torture and terrorist tactics carried out by both the Algerians and the French while waging the Algerian war. This did not sit well with the French government that the public should be made aware of this. They banned it from theaters for three years.

Writer-director Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless) allows his opinions to supersede the story line, making his films sound preachy and him self-indulgent. He often paints big political pictures that easily fall into generalizations. In his political assessments, he is just as apt to be artless as he is riveting. That is the case in his second feature, the brooding atmospheric “Le Petit Soldat.” Godard did not really have a clear position on the war and wavered in his opinions of it just like the film’s protagonist does, though probably having a position that was nearer to the one the right-wing had.

Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor) is a Secret Agent, a man of no political ideals, recruited while living in Geneva to do contract assignments for the French government. He is held in compliance by them because he’s a deserter who could be arrested at their discretion and sent back to France for punishment. He is assigned to kill an underground leftist Arab leader named Palivoda, but balks at the assignment for no apparent reason except he is undergoing a philosophical rebirth.

Bruno changes from being a hit man and becomes an art lover and intellectual. This comes about when he meets his dream girl, the mysterious woman of Russian ancestry who lived in Denmark, Veronica (Anna Karina-Godard’s wife at the time). His main concern is now whether Veronica’s eyes are Velazquez-grey or Renoir-blue. The film was fun when it had this mixture of lighthearted romantic notions and a dark political mood to it, almost making it seem like a noir film.

As Bruno tries to kill his target but can’t because as he explains this is not his real trade, he becomes philosophical and through a voice-over he intellectually muses on Godard’s thoughts. This results in temporarily turning off of the film’s energy. He says such inane things as Bach is good to listen to at 8 a.m., Mozart at 8 p.m., and Beethoven at midnight; that fiction and reality have become the same for him; that perhaps regret is the start of freedom; that it is ludicrous for the Vatican to be against Communism, since they both have the same belief that all men are brothers; and, that France will lose the war in Algeria because it doesn’t have an ideal.

Bruno is betrayed, but not by Veronica — who is secretly working for the Arabs but is crazy enough to fall in love with him — but by others. He is tortured by Algeria’s FLN, but does not reveal his contacts. He tells Veronica after he escapes, he didn’t squeal because they would have killed me anyway, whatever I did.

Warning: spoiler to follow in next paragraph.

Bruno is soon tailed by French agents after his escape and can’t runaway in time with Veronica to Brazil and is thereby forced to kill the underground leader, as the French grab Veronica and torture her. When Bruno boldly kills Palivoda in public to save his girlfriend, he learns that the French had already murdered Veronica.

This early, minor work by Godard, is a good example of how his films will later on look. Le Petit Soldat suffers from flaws due to its murky plot and in the director’s inability to bring out all the dramatic tension. What his aim seems to be, revolves less around plot and more in telling about the stench coming from the Algerian war explored through Bruno’s intellectual musings. Godard is most clear in showing that the Left and Right are two sides of the same coin. He is also innovative in his cinematography, challenging the conventional way of making a film by using jump-cuts and quick-editing, which gives a look of immediacy. This film, thankfully, didn’t have all the polemics of Godard’s later works, instead there’s much to find that is enjoyable and I dare say perceptive; especially, if you can overlook the director’s pedantic ways.

REVIEWED ON 1/18/2001 GRADE: B