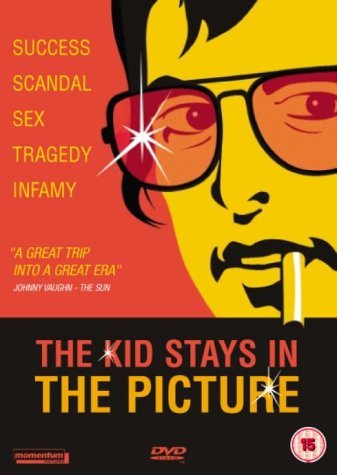

KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE, THE

(director: Nanette Burstein/Brett Morgen; screenwriter: Brett Morgen/from the book by Bob Evans; cinematographer: John Bailey; editor: Jun Diaz; music: Jeff Danna; cast: Bob Evans (Narrator), Francis Ford Coppola, Mia Farrow, Roman Polanski, Ali MacGraw, Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, Henry Kissinger; Runtime: 93; MPAA Rating: R; producer: Graydon Carter; USA Films; 2002)

“The documentary styled pic though entertaining was nevertheless irrelevant.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Oily Paramount film mogul Bob Evans tells his side of things in this biopic. It’s hard to warm up to this self-promoting lightweight, but his story has some interest for those tuned into the shallow side of Hollywood. Evans keeps things funny with his rapid-fire delivery and knack for doing uncanny voice imitations of the celebs. The co-directors and producers Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen (“On the Ropes“) are clearly on Evans side and do a fine job keeping the egomaniacal Evans’ story amusing, and supply some gorgeous photos and interesting archive footage to go along with the film’s breezy tone. Even though Evans might be a jerk and lacks artistic taste, he did run Paramount and has been associated with them for 35 years (which might tell you, that one doesn’t have to be genius to run a studio). It was under his helm that such greats as Rosemary’s Baby, The Godfather, and Chinatown were produced. There was also Love Story, a smash at the box office but one of the vilest cliché movies ever. Other noted films he was involved in as an executive include: The Odd Couple, Harold and Maude, Urban Cowboy, True Grit and his big flop The Cotton Club.

Evans narrates his sudden rise in Hollywood lore with a mixture of schmaltz, self-importance, and mock surprise and pleasure at his success (as if it just came to him and he didn’t seek it out!). He opens his narration stating “There are three sides to every story: my side, your side and the truth. And no one is lying. Memories shared serve each one differently.” The slickly handsome New Yorker was involved in a sportswear line called Evans-Picone, where his older brother was in charge. He had no luck breaking into Hollywood even though he started as a child actor. His film career got started in 1956 as a result of a lucky encounter. He was mingling poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel when the great screen legend Norma Shearer approached him about a small role in the Cagney picture “Man of a Thousand Faces,” to play her late movie mogul husband Irving Thalberg. The next year legendary producer Darryl F. Zannuck spotted the ladies man in NYC’s famous El Morocco nightclub and offered him a bit part as a bullfighter in Hemingway’s The Sun also Rises, which he trained three months for. Zannuck was sent a telegram voicing most of the casts displeasure at his hiring, those signing included Hemingway, Tyrone Power, Ava Gardner. and Eddie Albert. But Zannuck shot back: “The kid stays in the picture, and anybody who doesn’t like it can quit!” Evans never took himself seriously as a potential great actor, and from then on resolved he’d rather be a Zanuck than a movie actor. Evans’ starring role in his next film, “The Fiend Who Walked the West,” was the one that was so bad it ended his acting career.

Though going nowhere in the film biz as far as his acting career, Evans tells us he got lucky and through a newspaper story he finds himself in 1967, at the age of 37, as head of European production at Paramount with no experience as a film executive. The studio was going through a difficult economic period and of the nine major studios, it was ranked last. Charles Bluhdorn, the chief of Gulf & Western, which had just acquired the studio, had been swayed by a New York Times piece on Evans written by Peter Bart to let Evans choose the films for the studio. The inexperienced Bart was rewarded for his good publicity by the new ‘boy genius’ and became his right-hand man. Through whatever means it takes to turn a studio around, Evans did it and saved the studio from ruin. In a matter-of-fact way he relays some gossip about working with Mia Farrow on Rosemary’s Baby and how he fought to get Roman Polanski to direct it above the objections of the New York boys. He ran the productions for the studio for about seven years, and in 1974 he opted to be a freelance producer while still maintaining lucrative connections to Paramount.

Evans narrates from his kingly home he bought from Norma Shearer, the Beverly Hills estate, Woodland, whose posh grounds has a swimming pool and lush gardens and enough luxuriously decorated rooms to comfort the entire cast of any of his films. There are photos of the vain man escorting some of the loveliest stars in Hollywood, schmoozing with Henry Kissinger, and affectionately telling how Jack Nicholson did him a big favor by flying to France to talk an industrialist into selling him back his estate. The bachelor swinger married starlet Ali MacGraw, but things started to change when she dumped him for The Getaway costar Steve McQueen while he toiled day and night producing The Godfather. By the early ’80s, Evans started losing some of his glamor. There was a cocaine arrest from a DEA sting, a rumored involvement in the murder of an unethical businessman backer of his The Cotton Club, years of obscurity when Paramount rejected him, and mental problems that caused him to check into a loony bin. But the 72-year-old is a survivor, and when Stanley Jaffe took over as head of Paramount, he payed back the favor Evans did for him as a young man and brought him back to the studio.

The documentary styled pic though entertaining was nevertheless irrelevant. I know as little about Bob Evans as I did before seeing the pic. There’s not an ounce of introspection to be had in this self-serving mogul. Evans is the kind of producer who gave us Chinatown and Love Story, and is proud of both as if the films were equal in worth. That should tell you all that you have to know about him.

REVIEWED ON 5/27/2003 GRADE: C +