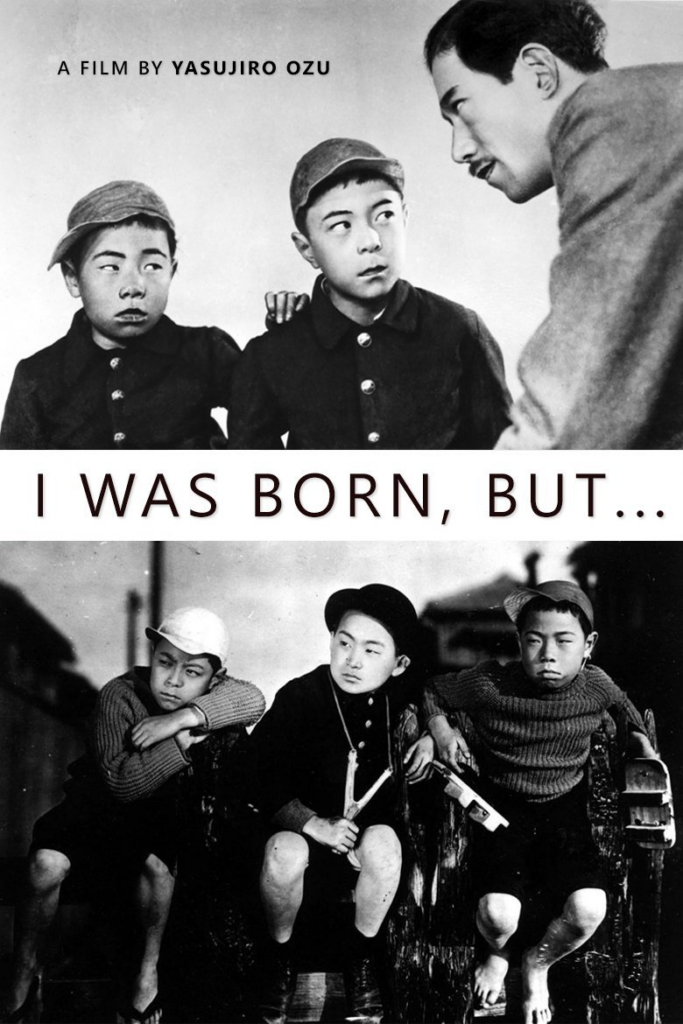

I WAS BORN, BUT… (UMARETE WA MITA KEREDO)

(director/writer: Yasujiro Ozu; screenwriters: Akira Fushimi/Geibei Ibushiya; cinematographer/editor: Hideo Mohara; cast: Hideo Sugawara (Older Son), Tokkan Kozo (Younger Son), Tomio Aoki (Keiji), Tatsuo Saito (Yoshii), Mitsuko Yoshikawa (Yoshi’s Wife), Takeshi Sakamoto (Iwasaki), Teruyo Hayami (Mrs. Iwasaki), Seiichi Kato (Taro), Shoichi Kojufita (Delivery boy), Seiji Nishimura (Schoolmaster); Runtime: 91; Shochiku Kamata studio; 1932-Jap.-silent)

“This splendid example of a salaryman’s film is the first great film of the master’s.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

The Shochiku Kamata studio specialized in nonsense comedies something the great director, one of the world’s most acclaimed, Yasujiro Ozu (The Tokyo Story/Late Spring/Floating Weeds), was keen on doing during this early period of his film career. He refused to make talkies until yielding in 1935. He continued to make silent social comedies somewhat in the style and somewhat equal to the Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton films, though Ozu’s films were seen through the eyes of children rather than taken from the adult’s point of view. They were ably co-scripted by the master of the nonsense film, Akira Fushimi. I Was Born , But… is a film with lots of sight-gags, and is made as a light social comedy. It turned darker as the story got a bit more involved with the patriarch of the family, Mr. Yoshii (Tatsuo Saito). This splendid example of a salaryman’s film is the first great film of the master’s, with many others to follow. It is a film about the lower-middle-class (shomin-geki) and it takes the form of a domestic drama, the kind of film Ozu continued turning out for his entire film career which spanned from 1927-1963. This life-long bachelor, ironically making family dramas, passed away at the early age of 60.

The depression came to Japan in 1927 and continued into the 1930s. By 1932, one out of five unemployed workers was a salaryman, as the banking system crashed. Haunted by the fear of unemployment the Japanese worker was a subservient figure, something that Ozu uses in this film to exploit his satire of the human condition and comment on the pecking order of society, where the rich remain in power no matter what the conditions.

The Yoshii family moves to the Tokyo suburbs, which places the lowly clerk near the residence of his boss, Mr. Iwasaki (Takeshi Sakamoto). This draws comments from Yoshii’s fellow clerks how he moved there to ingratiate himself further with the boss. The two Yoshii sons, the ten year old (Hideo Sugawara) and the eight year old (Tokkan Kozo), have a tough time fitting in with the other kids in the neighborhood, who pick on these newcomers. Among the bullies is the boss’s son, Taro (Kato), but the big bully of the group is Keiji (Aoki). There is a sandal fight among the boys, which brings out the film’s visual humor. The framing of the shots magnifies the synchronized reactions of the two fighters.

Ozu has fun with the bully who takes away the puzzle-ring from the little brother, but is baffled about how to work it. The group scares the brothers so much, that on the first day of school, they play hooky. Since their father gave them a stern pep talk expecting them to get an “E” on their work, with that letter standing for excellence, the boys feel obligated to paint a picture to show their dad what they did in school. But they do not feel capable of imitating how a teacher makes an “E”, so they get a parked beer-delivery truck’s young adult driver to forge the grade. He slyly puts an “F” there and smiles as he leaves the students unaware of what he did. Before arriving home the father runs into the older boy’s teacher, who acts concerned why the children didn’t show up for school. This results in a lecture by the father that he wants his sons to attend school and grow up to be great men. After being told the reason why the boys skipped school he tells them that if the gang bothers them again, just ignore them and they will go away. The boys are not satisfied with this answer, but still look up to their father. In fact Ozu’s camera angle for adults when talking to children is always taken from a higher elevation so that the adults are talking down to the children, always in a position of superiority.

The older brother is the braver and more cunning one and when he is again confronted by the hostile boys, he realizes that today is payday for his father and his mother (Mitsuko) can afford to buy some beer for her husband. He tells the delivery man about this, who becomes very pleased with the boys after the boys’ mother bought six bottles of beer from him. So when the older brother asks him as a favor to them if he can beat up the bully, he obliges them, sending the bully home crying. But when he is asked to also beat up the boss’s son — he tells them, no. His family buys more beer than yours.

The boys when they return to school the next day, under the watchful gaze of their father, find themselves being accepted by the group. Ozu draws the analogy of the workplace power structure to the way children naturally socialize and states that the adults’ power is vindictively used in the social arena and is derived from one’s station in life and how much money one has.

Later on, the children are seen playing games together and the brothers prove to be good at also being bullies and are telling the other children that their father is greater than anyone else’s. The game they play is a mock power game of killing by giving one the evil eye, while the other falls down pretending to be dead. They also comically cross themselves in a parody of a Christian ritual. But when Yoshii comes on the scene and sees Taro lying on the ground he quickly picks him up and brushes him off, to the disappointment of the boys.

The question of submission becomes the motif of the film, as Yoshii is seen by the boys bowing to Taro’s father and they don’t understand this. For them Taro is not as smart or as strong as they are, so why should their father submit to his father!

That Yoshii was an inferior man was made clear from the first scene on, where he is humiliated that his truck got stuck in the mud and the boys have to push him out. And that before he even gets settled into his new house, he runs over to his boss’ house and kowtows to him.

The film shifts gears and the comedy now becomes dark as Yoshii is at the boss’ house watching home movies and the boys are also there as guests of Taro, and what they see results in their loss of innocence. The home movies become unbearably embarrassing to watch for Yoshii and the children, as Yoshii acts the part of the clown and is seen as an obviously inferior man than his boss. He is seen looking up to the boss all the time and performing in order to please the boss. Yoshii himself is embarrassed that he has to lower himself so much, but he is secretly pleased that he is so successful as a clown and can make everybody laugh. In the house, while watching the movie, he is doing what he did on film, rushing to light the boss’s cigarette and trying to ingratiate himself to the boss in anyway he can. Taro’s only comment is, your father is really funny. But the boys can’t take being in the same room with their father anymore and run out of the house. Ozu’ other purpose of showing the home film, being always the gag-man, is that it gives him a chance to parody his own way of shooting films by having the home movie filmed in the same style he uses for this movie; such as, using the same tracking shots and camera height angles. He even has some of the boss’s other guests yawning at parts of the movie where he shows boats and cars.

Back in the house, the boys throw a tantrum as they react to their father’s answers to their constant barrage of questions they hurl at him. Asking him, why does he bow to the boss? The wry salaryman responds, “If I didn’t, I wouldn’t get paid and you wouldn’t eat.” Ozu’s implications are clearly centered around the social use of power, comparing the boys rise in stature into their neighborhood as being determined by who is tougher and smarter. The boys’ illusion is that all power can be won through one’s talents. But in the business world the boss doesn’t have to possess those character traits, he is the boss because that is the way society is structured and it pays to submit to that hierarchy or else you will be left out in the cold to fend for yourself.

The childish reaction of the boys to all this, is that they decide not to eat anymore. Here, the mother takes over the next day and cooks up some delicious looking rice cakes for the boys to eat, which they eventually will. Their father casually joins them and there are no more pretenses about who he is, as they eat and talk in a natural manner. When the father encourages them to keep going to school, to try to become great people, he also asks the younger one what he wants to become and he says: “A lieutenant general.” The father then says, “Why not a general?” And he responds, “Because my brother will be the general.” And things seem to be back in order, everyone knows their place in life and the sham of the father having to be regarded as a great person is no longer carried out. The relationship is now an honest one after the healing process is completed. The “but” in the film’s title comes into place, as it indicates that everyone is born equal “but” that changes soon enough. There is always something to disturb the stability assumed from the outset. Ozu affirms the necessity of the family sticking together to face these social challenges as the best chance everyone has of making it successfully through life.

The only time we see the father and mother talking seriously together is after the children throw their tantrum and she tells the disconsolate husband I hope the boys have a better life than we did and he takes out a bottle of whiskey, prepared to drown out his shame and low conception of himself with forgetfulness as he pragmatically responds: “They’ll have to live with it all their lives.” When he and his wife check in on the sleeping brothers, they ask themselves: “Will they lead the same kind of miserable lives we have?” It is now clear that Yoshii grovels because he can’t do anything else about it. And like many parents in America he only wishes his children have a better life than he does, which draws him closer to the audience and presents him in a more sympathetic light.

In the closing scene, after the reconciliation is made among the boys and the father, the boys tell Taro that his father is the greatest and now encourage their father to bow to Taro’s father. And to further emphasize the pecking order that exists and is realized by the no longer innocent boys, the bully rushes down the street to make sure the teacher sees him doff his cap. The plot of the film is encompassed within a short five-day period and it parallels in a didactic way the social structure of the children and the grownups, and how in each group adjustments have to be made in order to survive. The majority of the film is concerned about how the boys start growing up. The adult world is mainly used as a expansion of the boys’ limited horizons.

REVIEWED ON 11/5/99 GRADE: A