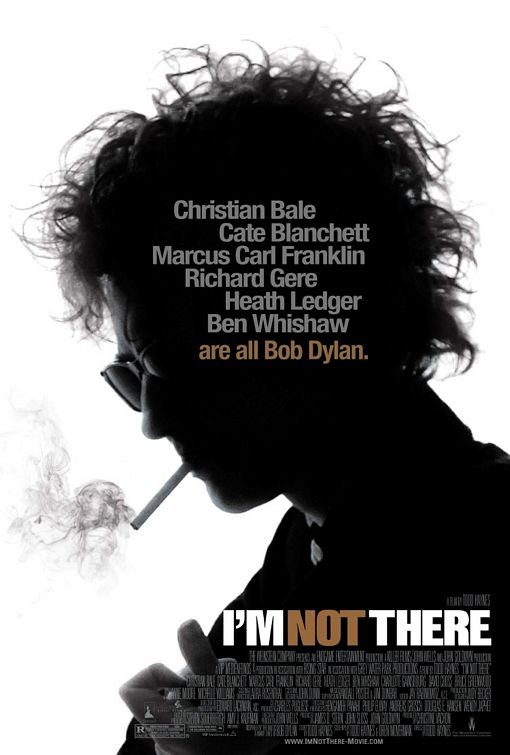

I’M NOT THERE

(director/writer: Todd Haynes; screenwriters: Oren Moverman/based on a story by Mr. Haynes; cinematographer: Edward Lachman; editor: Jay Rabinowitz; cast: Christian Bale (Jack/Pastor John), Cate Blanchett (Jude Quinn), Marcus Carl Franklin (Woody Guthrie), Richard Gere (Billy), Heath Ledger (Robbie), Ben Whishaw (Arthur Rimbaud), Kris Kristofferson (Narrator), Charlotte Gainsbourg (Claire), David Cross (Allen Ginsberg), Bruce Greenwood (Keenan Jones/Pat Garrett), Julianne Moore (Alice Fabian), Michelle Williams (Coco Rivington), Richie Havens (Old Man Arvin), Peter Friedman (Morris Bernstein), Alison Folland (Grace), Yolonda Ross (Angela Reeves), Kim Gordon (Carla Hendricks), Mark Camacho (Norman), Joe Cobden (Sonny), Kristen Hager (Mona); Runtime: 135; MPAA Rating: R; producers: James D. Stern/John Sloss/John Goldwyn/Christine Vachon; Weinstein Company; 2007)

“The iconoclastic film about the idiosyncratic artist is truly an inventive film but not an easy one to come to grips with or instantly enjoy.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Todd Haynes (“Safe”/”Far from Heaven”/”Velvet Goldmine”), a graduate of the semiotics department at Brown University, directs and co-writes with Oren Moverman this overlong, personal, ambitious, audacious, messy, visionary, gimmicky and unconventional biopic on the legendary singer/poet Bob Dylan—someone Allen Ginsberg called the voice of his generation. It’s a film that never makes up its mind about where it’s going or what it wants to be; its mock documentary structure, its cutting back and forth between six Dylans to make schoolboy points, and all its hypothetical postulates leave it as a speculative academic essay for Dylan scholars rather than as a biographical film as promised. It’s a film that never turned me off, but also never turned me on. It romanticizes and hero worships Dylan in ways that I never dreamed of when I listened to his anti-establishment music during the 1960s and cared only that he was expressing what I was thinking.

Haynes casts six diverse actors to play the mysterious Bob Dylan, with the frizzy-haired wigged actress Cate Blanchett—doing a male impersonation—being the most inspired choice and probably the main reason for seeing the film for those who are not Dylan fans or who are not familiar with his music; the African-American youngster Marcus Carl Franklin as the fake Dylan escaping from a troubled childhood was the cutest casting decision and using him to show the influence that blacks had on the folk music scene worked in an odd magical way; while the casting of Richard Gere as the cowboy outlaw Billy the Kid, showing Dylan’s lifelong love affair with various outlaws, never got on track and seemed a wasted effort, as it did little to tell us anything about Dylan worth knowing.

For those looking to know something straightforward about the celebrated legendary figure, this is not the film for them (try Scorsese’s No Direction Home for a somewhat clearer factual biopic!). I’m Not There tells us little, if anything, that can be taken without a grain of salt about the Jewish kid born Robert Zimmerman in 1941 in Duluth, Minn., who reinvented himself as an enigma and revolutionized the American pop music scene after he left his hometown in the 1960s for Greenwich Village and took his surname from the Welsh poet and borrowed his folk style, in the beginning, from Depression-era legend Woody Guthrie.

The six Dylans are played by Christian Bale (Jack Rollins), Cate Blanchett (Jude Quinn), Carl Franklin (Woody Guthrie), Richard Gere (Billy), Heath Ledger (Robbie), and Ben Whishaw (Arthur Rimbaud). The artist as the 11-year-old black child who poses as Woody Guthrie, has a guitar case with Guthrie’s motto written on it — “This machine kills fascists,” rides the boxcars with the hobos, sings in 1959 radical songs from the 1930s, and is told by a maternal black lady “Live in your own time;” he then has a metamorphosis into Jack Rollins the tormented “troubadour of conscience” of Greenwich Village’s early ’60s folk scene at the coffeehouses, who sings popular protest songs that are “finger-pointin'”(Bale will later reappear as Dylan-the-born-again-Christian); then the Rollins character suddenly morphs into hipster Hollywood actor Robbie Clark, who plays Dylan in a fictional film when he was in the early ’70s a superstar trying to come to terms with fame and a failing marriage to the celebrated painter played by Charlotte Gainsbourg (a composite of his two wives Suze Rotolo and Sarah Dylan); Jude Quinn appears next as an obnoxious drugged-out intellectual poser and represents the electric Dylan at his peak years in the mid-’60s—the one who upsets the traditional folk music folks at Newport, using his guitar as a machine-gun to mix folk tunes with a hard rock sound and who then tours ‘Swinging England’ to a hostile reception by journalists and a booing audience expecting the old Dylan— whose anger is sparked by a concert patron calling him from the balcony a Judas; The fifth Dylan is a 19-year-old Symbolic poet named Arthur Rimbaud (Ben Whishaw), Dylan’s early muse who mouths off impassionately as a man of letters advocating his anarchist and libertine beliefs but who can’t adequately explain himself to the satisfaction of those straights (journalists, political subcommittees, humanitarian groups!) who grill him but don’t dig him when he doesn’t say what they want to hear. The sixth Dylan is a retired Old West outlaw named Billy (Richard Gere) living a life of anonymity after faking his own death, but comes to life again in the frontier town of Riddle, Missouri, when he discovers that the town is to give way for a new highway.

The iconoclastic film about the idiosyncratic artist is truly an inventive film but not an easy one to come to grips with or instantly enjoy. It’s taken from the impressions of the director who was born in 1961, just about the time Dylan was emerging on the American pop scene, and reflects a vision of the singer as viewed from a distant time and not by someone who was into Dylan like those the same age who grew up in his era and were of the same mindset (like I was) when he was the most celebrated and resonant counterculture voice waxing poetic about the changing times.

There’s lots of insider references to check out for “Dylanologists” who care to go that route and who care to see the film a number of times to catch all that’s missed by just one sitting. For starters, there’s the film’s title that’s lifted from the bootlegged track from the “Basement Tapes” sessions that never made its way onto an official Dylan album.

The arty fragmented film left me feeling I was not there because it provided me no room to make an emotional connection with any of the characters who are supposed to be parts of Dylan’s persona but come off merely as caricatures wearing masks, its facts are spotty, it failed to demystify him in its supposed attempt to demystify him, and it was far too abstract to be involving. It can be viewed more as a great idea for a movie that simply wasn’t a great movie. Though the Dylan music was there, it somehow felt out of place in such an artificial setting. To clear my head of a film I failed to enjoy as much as I would have liked to, that old time feeling for Dylan returned only when I retreated to his Blonde on Blonde album and felt rejuvenated in a way the movie never was able to do for me after one viewing (in a film I know demands more than one viewing, yet I’m content to stick with my initial impression).

REVIEWED ON 1/9/2008 GRADE: B https://dennisschwartzreviews.com/