HUMAN NATURE

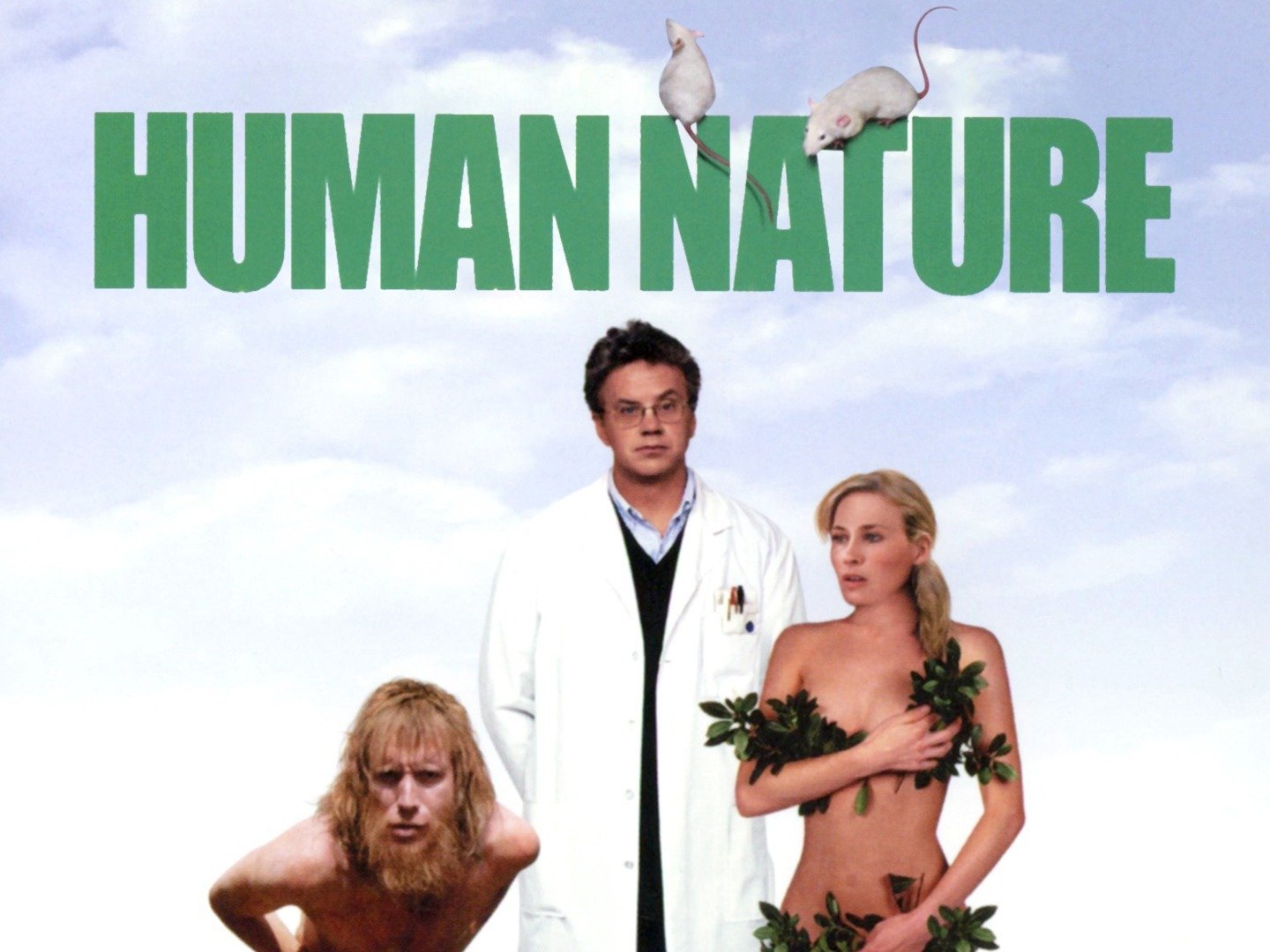

(director/writer: Michel Gondry; screenwriter: Charlie Kaufman; cinematographer: Tim Maurice-Jones; editor: Russell Icke; music: Graeme Revell; cast: Tim Robbins (Dr. Nathan Bronfman), Patricia Arquette (Lila Jute), Rhys Ifans (Puff), Miranda Otto (Gabrielle), Rosie Perez (Louise), Robert Forster (Nathan’s Father), Mary Kay Place (Nathan’s Mother), Nancy Lenehan (Puff’s Mother), Miguel Sandoval (Wendall the Therapist), Anthony Winsick (Wayne Bronfman), Peter Dinklage (Frank); Runtime: 96; MPAA Rating: R; producers: Charlie Kaufman/Spike Jonze/Ted Hope/Anthony Bregman; Fine Line Features; 2001)

“Plays as a sophomoric exercise in the art of satire.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

“Human Nature” plays as a sophomoric exercise in the art of satire. When this satire about the differences between civilized and uncivilized behavior doesn’t work, which is for most of the film, it really stinks up the joint. Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman who got it right in “Being John Malkovich” tries another goofy screenplay, but has no such luck. Just about everything goes wrong, as the laughs are merely from throwaway lines, the characters play to their clichés and try to be too cute for the viewer to engender any real concern for them, and the script gets reduced to silly prattle and is never able to have an edge. If going ape for just the sake of going ape is your idea of returning to nature, and if you find it delightfully absurd that one of the main characters who believes he’s an ape-man can go before Congress and deliver an erudite speech encouraging the lawmakers to pass a law bringing people back to nature (something that is obviously impossible to ever enforce), then as absurd a satire as “Human Nature” is it still might agree with you more than it did with me. It tries to throw in whatever it could to get a laugh, even a dwarf (Dinklage) is awkwardly fitted into the story. Its attempt to study human behavior as compared to animal behavior is ludicrous. It goes overboard with its undeveloped theme to explain man’s evolutionary gains at the expense of losing the thrust of his animal instincts. A motto to explain modern man’s troubling sexual behavior is exclaimed by the film’s repressed scientist: “When in doubt, don’t ever do what you really want to do.”

Human Nature is directed by Michel Gondry in his feature debut. He’s the music video specialist who is best known as a commercial director for several Levi’s ads, and has worked with the singer Bjork. What he’s trying to sell here is a film that is too slight, and though the talented cast tries its hardest to make something out of the one-note script — it’s all in vain.

The film starts from its conclusion and in flashback tells how an anal affected research scientist, whose special federally funded project is to teach table manners to mice, Nathan Bronfman (Tim Robbins), was murdered in the woods. Lila (Patricia Arquette) confesses to the crime, even though she didn’t do it, because she has an ulterior motive. The story then gets told from the point of view of each of the three main characters involved: Nathan, Lila, and Puff (Rhys Ifans). Nathan apologetically tells his side of events from the otherworld, and explains how his adoptive parents (Robert Forster and Mary Kay Place) brought him up to reject his natural instincts and suffocated him with their warnings about the evils of natural life: “Never wallow in the filth of instinct”.

The film opens showing that Lila has retreated to the woods at the age of 20 because of an hormonal defect that left her body entirely covered with hair. She becomes a noted reclusive best-selling nature writer and prances around nude in the woods (covered with a veiled body shirt of hair, which makes it hard to see her completely nude), but is happy to be among the wild animals because they are nonjudgmental of her appearance. But she becomes frustrated for sex and comes into town to get electrolysis from Louisa (Perez), and hopes she can have all her body hair removed so that she can meet an intelligent man who will accept her for what she is. Louise gets her a blind date with the scholarly 35-year-old virgin Nathan, whom she says won’t notice her hair problem because he’s too worried about his small penis. She knows all this about him from her therapist brother Wendal (Sandoval), who is treating Nathan.

The two misfits compromise their extreme opposite beliefs about nature so that they can have a relationship, but she goes even further and eventually compromises all her cherished nature and feminist principles just to keep him. On a hike in the woods, they discover a naked feral man prancing around like an ape because he thinks he is an ape. His mentally ill father thought of himself as an ape and raised him that way also in the wilderness to be in a pure state of nature, after he snatched him from his mother. Nathan takes him back to his lab as a subject and places him in a Plexiglas cage and trains him by electric-shock-driven behavior modification, and soon subdues his aggressive sex drive and turns him into a properly cultivated man who reads Yeats. Figuring this will get him recognition in the scientific community, Nathan doesn’t concern himself that his subject is a human being and not a mouse. Nathan’s slinky sexy French lab assistant Gabrielle names the ‘nature boy’ Puff.

The film tries to answer the question if there’s a middle ground between natural impulses and the restrictions imposed by civilization. It does it in a screwball comedy manner, as the three manage to get involved in a very civilized menage a trois that makes Nathan’s simplistic experiment all the more complicated. And to add a little more of a splash, you can throw the sexually driven lab assistant into the menage a trois mixture. But after this setup comes to fruition, Gondry seems to be clueless on how to expand the story and take it somewhere. The film gets lost in the woods and in the process loses its comic timing, its purpose, and the ready mood it had set for a controlled craziness. It all seemed forced, as the film just had no finely tuned aesthetic rhythm to carry out its madness.

REVIEWED ON 1/7/2003 GRADE: C –