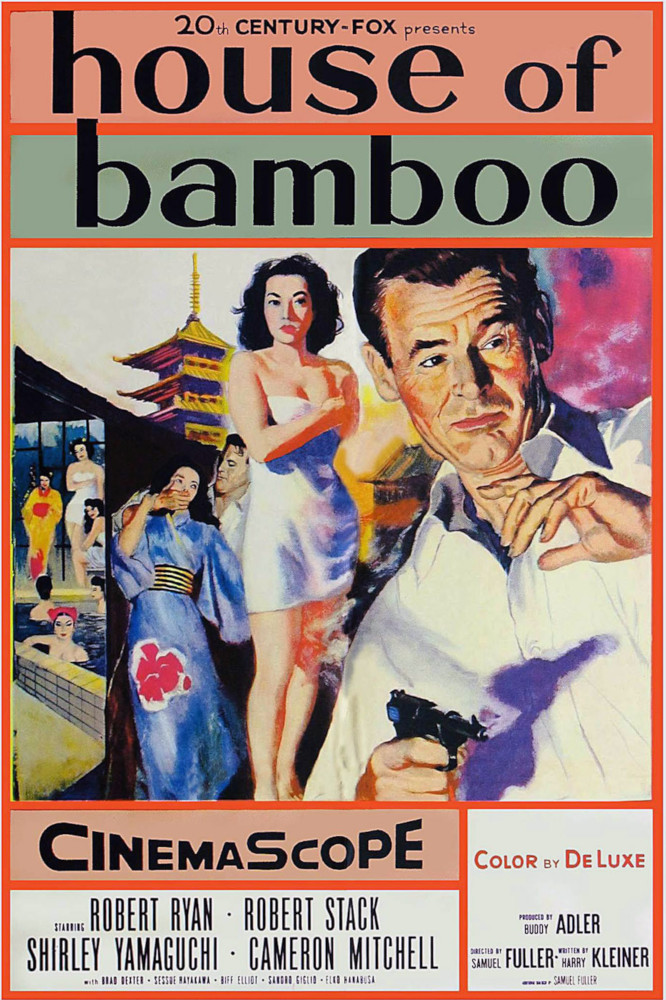

HOUSE OF BAMBOO (director/writer: Samuel Fuller; screenwriter: Harry Kleiner; cinematographer: Joe MacDonald; editor: James B. Clark; cast: Robert Ryan (Sandy Dawson), Robert Stack (Eddie Kenner/Spanier), Shirley Yamaguchi (Mariko), Cameron Mitchell (Griff), Brad Dexter (Capt. Hanson), Sessue Hayakawa (Inspector Kito), Biff Elliot (Webber), Sandro Giglio (Ceram), DeForest Kelley (Charlie); Runtime: 82; 20th Century-Fox; 1955)

“Fuller, as always, is resourceful and fresh.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

In 1954 an American crime syndicate made up of ex-GI’s and organized by a devious psychopath, Sandy (Ryan), rob a train of machine guns. An American soldier in on the robbery, Webber (Biff), dies not telling the police who is the boss. But his U.S. Army interrogators, in a joint investigation with Japanese authorities, discover he has secretly married a Japanese woman, Mariko (Yamaguchi). Webber tells the lead investigator, Captain Hanson (Dexter), that if anyone should find out that he is married to Mariko, she would be in grave danger.

The Army assigns an undercover agent, Sergeant Eddie Kenner (Stack), who uses the name Eddie Spanier as a cover-up for his real identity. The real Spanier is currently in prison for armed robbery and is a good friend of Webber, from their Army days.

In the cop’s first assignment as Spanier, he visits Mariko and feigns disappointment when she tells him her husband is dead. He then goes into a Tokyo pachinko parlor and demands protection money from the boss, but is roughed up by the gang’s ichi-ban (number one man) — Griff (Cameron).

After he is closely checked out by the gang’s leader, Sandy, who gets a hold of Spanier’s police record through his police connections, he is taken into the gang. He uses Mariko as his “kimono girl”(someone who takes care of him sexually). He uses her, thinking that she is someone he could trust to get word to Captain Hanson of his activities, in case he runs into trouble with this dangerous assignment.

The rule of the gang is that if one of them gets wounded, the others must shoot him. This way no one talks if captured. On Spanier’s first caper, in a factory, the robbery turns violent and he is wounded. But Sandy against his own orders, rescues him. He thereby comes to favor Eddie to the disgust of Griff. There’s a hint of homosexuality in the Sandy character, though we see nothing overt to confirm what we feel.

One of the most absurd scenes, even for someone like Fuller who lives to film wacky scenes, is in the teahouse where the American gangsters are partaking of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony and Griff confronts Sandy about not being close to him anymore. He rants: “I’m your ichi-ban, not that newcomer. Why can’t I go with you on the next job?”

Warning: spoiler to follow.

Fuller’s main motifs are: dual identities, betrayal, and racial conflict. All play a major part in the postwar story set in Japan. His busy camera is everywhere: catching the evil smirks of the gang members, the crowded Ginza district’s feverish atmosphere, a Kabuki troupe member talking to a foreigner; and, in the climactic amusement park scene that features a whirling globe (as if the whole world is spinning out of control), Fuller has Eddie gun down the crime boss as the globe continues to whirl.

This is a particularly violent film noir, whose subject matter offers a penetrating look at the American occupation of Japan. It is basically saying that what the U.S. is doing is criminal. It also magnifies the huge cultural bridges the two countries have and why it is so difficult for them to get to know and trust one another. This is highlighted by the very formal structure of the love relationship between Mariko and Eddie. Eddie is always viewed as a foreigner and can’t be fully accepted, no matter what he does. Their love story seemed empty, there was a psychological separation between the two that couldn’t be reconciled.

Even though the story had a lot of loose ends and didn’t make sense most of the time, the strangeness of the characters and the oddness of the location made for a telling tale.

Fuller, as always, is resourceful and fresh. His films guarantee the viewer a jolt or two of electricity. Here the number of jolts is much higher, thereby making this an even juicier Fuller film. The iconoclastic Fuller just goes into a film and grabs what he wants out of it.

REVIEWED ON 4/16/2000 GRADE: B

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DENNIS SCHWARTZ