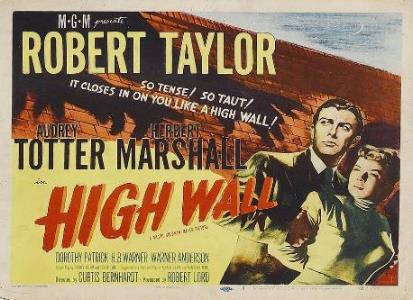

HIGH WALL(director: Curtis Bernhardt; screenwriters: from the play by/ Lester Cole/Sydney Boehm; cinematographer: Nicolas Vogel; editor: Conrad A. Nervig; music: Bronislau Kaper; cast: Robert Taylor (Steven Kenet), Audrey Totter (Dr. Ann Lorrison), Herbert Marshall (Willard I. Whitcombe), Dorothy Patrick (Helen Kenet), Bobby Hyatt (Richard Kenet), Vince Barnett (Henry Cronner), Warner Anderson (Dr. George Poward), Morris Ankrum (Dr. Stanley Griffin), Moroni Olsen (Dr. Philip Dunlap), John Ridgely (Asst. District Attorney David Wallace); Runtime: 99; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Robert Lord; MGM; 1947)

“A tepid and chatty psychological melodrama.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Warning: spoilers throughout.

German refugee Curtis Bernhardt (“Conflict”) directs a tepid and chatty psychological melodrama that is embellished with black-and-white film noir visuals by the adept camerawork of Nicolas Vogel. High Wall relates the story of an innocent man, Steven Kenet (Robert Taylor), a much decorated ex-army pilot, who returns from Burma to find his wife Helen (Dorothy Patrick) living in the apartment of her boss Willard Whitcombe (Herbert Marshall). His first reaction is rage as he strangles her, but he blacks out not remembering if he actually killed her. But since he’s found unconscious behind the wheel of a crashed car next to his dead wife, he confesses to murdering her and is arrested. Steven has a wartime brain injury that needs to be operated on to remove a blood clot; it causes severe headaches, mood swings and blackouts. Steven refuses the operation, realizing he will be sent to a mental institution and not be held legally responsible for the crime. He is committed to a veteran’s mental institution which is surrounded by a high wall. While there Dr. Ann Lorrison (Audrey Totter) takes an unusual interest in him and talks him into undergoing the operation and finding out the truth. When the operation is a success and he still can’t recall what happened to Helen, he agrees to Ann’s request to undergo narcosynthesis (truth serum).

While under the truth serum’s influence Steven relates to Ann that his marriage was a wartime romance and that he later found his wife to be more materialistic than warm and cuddly. She discouraged him from taking a low paying job at the university, a job he really wanted, and instead he went to work in Burma at a higher paying but not pleasing to him job. While he was away for a few years Helen became secretary to Whitcombe, a stodgy executive with a conservative religious book publishing company.

The drug session proves not to be conclusive of whether or not Steven committed the crime, so he breaks out of the sanitarium and revisits Whitcombe’s apartment with Ann reluctantly going along despite jeopardizing her career. Steven jogs his memory recreating his break-in on Helen and realizes one item is missing, the overnight bag Helen had on the bed. Soon he is visited by Whitcombe, who knows Steven was in his apartment. The clever Whitcombe taunts Steven by telling him he killed his wife and the janitor Cronner who saw him leave with the bag, which causes Steven to violently attack him and be restrained by the orderlies. Steven is put in isolation as a result of Whitcombe’s skullduggery, but manages to escape and evade a police manhunt as he tries to confront Whitcombe in his apartment. Ann finds Steven in the street outside Whitcombe’s building and the two sneak into Whitcombe’s apartment, where Ann unethically injects Whitcombe with a truth serum. The truth comes out and the police release Steven into the waiting arms of Ann. Steven also gains custody of his 6-year-old son Richard, who he loves very much and was temporarily staying with Ann and her Aunt Martha while his father was confined.

The film’s most noirish scene is when Herbert Marshall casually disposes of the janitor, who is on a stool repairing the elevator, by slipping the handle of his umbrella around the stool’s legs causing the janitor to fall to his death down the elevator shaft. Marshall makes for an oily villain, who confesses he murdered Helen because a scandal would ruin his chances of becoming a partner in the publishing firm. The other main performers are adequate but too bland to convince us that their romance was possible. Robert Taylor’s personal despair was more like angst in a soap opera than film noir. The film’s biggest faults were that it was never convincing as a mystery story, that the romance story was more Hollywood fantasy than real, that the truth serum is so casually accepted as the answer to establishing the truth and that brain surgery can so easily cure Taylor of his mental disorder.

REVIEWED ON 9/23/2004 GRADE: B –