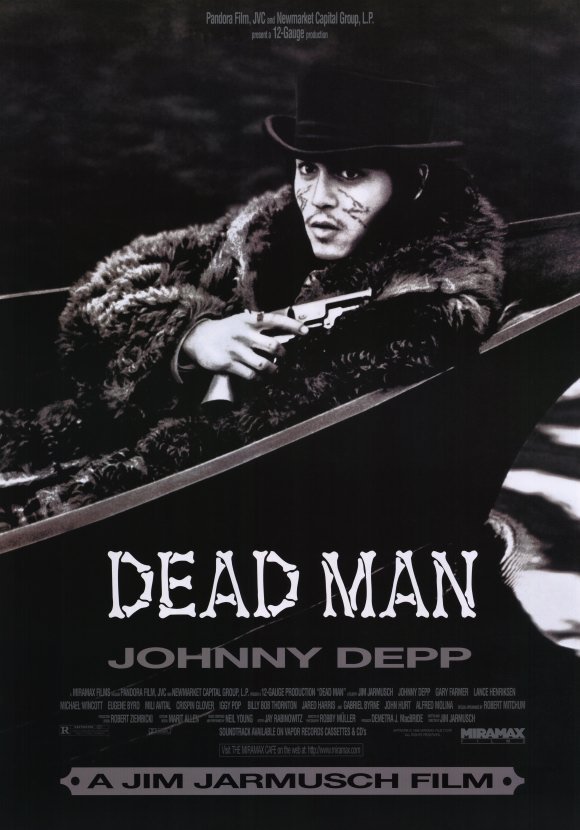

- DEAD MAN

(director/writer: Jim Jarmusch; cinematographer: Robby Müller; editor: Jay Rabinowitz; cast: Johnny Depp (William Blake), Gary Farmer (Nobody), Lance Henriksen (Cole Wilson), Michael Wincott (Conway Twill), Eugene Byrd (Johnny “The Kid” Pickett), Mili Avital (Thel Russell), Gabriel Byrne (Charlie Dickinson), John Hurt (John Scholfield), Iggy Pop (Salvatore “Sally” Jenko), Billy Bob Thornton (Big George Drakoulious), Jared Harris (Benmont Tench), Jimmie Ray Weeks (Marvin, Older Marshall), Mark Bringelson (Lee, Younger Marshall), Michelle Thrush (Nobody’s Girlfriend), Alfred Molina (Trading Post Missionary), Robert Mitchum (John Dickinson), Crispin Glover (Fireman); Runtime: 120; Miramax Films; 1995-USA/Ger.)

“It is an American masterpiece…”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Jim Jarmusch (Stranger Than Paradise/Permanent Vacation/ Down by Law/ Mystery Train/Night on Earth) has directed and written a poetically unique and disturbing Western. It is an American masterpiece and one of the best films of the ’90s. The electrical guitar played and scored by Neil Young complements the eerie mood of the film, as Young’s improvised melodic theme is repeated with different strains and variations throughout. The film could also be viewed as if one were reading a book of poems as each scene is separated by a blackout, which allows the next scene to be read as a new poem or viewed as a new development in the film — one that is not necessarily related to the previous scene.

The film opens with a written quote onscreen from the French surrealist poet Henri Michaux — “It is preferable not to travel with a dead man.” This sets the tone, which will take a jaundiced look at how the white man settled the West and abusively treated the Native Americans. This film is viewed on the side of the outsider, the loner, and the visionary, who have the wherewithal to see through all the violence that America is built around in its pursuit of happiness and economic comfort. Aside from Jarmusch’s deadpan humor, the dreamlike intonations, the psychedelics, and the surreal camerawork (a beautifully shot black-and-white film by Robby Müller is slowly unfolding, one that catches hold of the deathlike odyssey sequences and the superb imagery of the landscape), there is also a strong history lesson and a colorful mystical tour of the death experience that adds an especially vibrant visionary sense to this stunning and problematical film.

In the late 19th century a meek, orphaned young man, foppishly dressed for his journey, clad in a checkered suit and bow tie, named William Blake (Johnny Depp), leaves Cleveland by train with a letter guaranteeing him a job as an accountant for the Dickinson Metal Works out West, in a town called Machine.

The train ride is a trip into the hostile frontier, where the rugged passengers will at one point open fire on a herd of buffalo going by. The white man is depicted as cruelly killing off for no reason the Indian’s natural food supply, just as easily as they performed genocide against the Native Americans. The only civilized conversation Blake has on the train comes from the fireman (Crispin Glover) who is smudged with soot on his face, telling Blake he can’t read his job acceptance letter because he is illiterate; but, forewarns, “I wouldn’t trust no words written on no piece of paper.”

Blake’s destination point is a squalid place, with no redeeming features or common civility. It is a menacingly dark and satanic mill town where he expects to find economic salvation. It is a comment on the Industrial Revolution and how it destroys people’s sensibilities and their environment, and takes away any hopes that they might have had for a quality life. The further bad news that comes Blake’s way is when he is derisively told by the office manager (John Hurt) at the Metal Works that the job was filled a month ago and when Blake demands to speak to the boss, John Dickinson (Robert Mitchum), he is told by the morbid Dickinson, to get the hell out of there before he shoots him with the shotgun he is pointing at him. To console himself, the low-on-funds easterner buys a small whiskey bottle in a saloon. When he comes out of the saloon, a former prostitute who is selling paper flowers and has the name of one of the real poet’s visionary muses, Thel (Mili Avital), gets pushed in the mud by some ornery local. Blake helps her up and the two misfits in town, find that they are kindred spirits and spend the night in her bed. This turns out to be unfortunate for the young man as Thel’s former fiancé, Charlie Dickinson (Gabriel Byrne), the son of the Metal Work’s boss, comes to visit her and when finding Blake, he attempts to kill him. But Thel takes the bullet meant for him. Blake, though critically wounded in the chest, uses her gun to fatally stop Charlie from killing him.

Blake escapes by horse and is spotted while lying wounded by a wise-cracking Indian calling him a stupid white man. The Indian realizes that the bullet is lodged permantly in his chest and that he will soon be a dead man.

The outcast Indian has taken the name Nobody (Farmer), which is a good indication of how the white man considered the Native Americans. He was captured by British soldiers as a youngster and paraded around to different cities in a cage and when he was brought to London, he aped the way the British talked and they gave him a chance to go to their schools. That’s where he read the Western world’s greatest visionary poet, William Blake, and knew he met someone who felt the same way about life’s meaningful things. When the young man tells him that he is named William Blake, Nobody thinks that he is a reincarnation of the poet and treats this white man with a new respect believing that he is a dead white man but his poetry is eternal; and, that is what he carries with him in spirit, even if he is ignorant of it. William Blake states that he is not a poet and doesn’t even understand poetry. Nobody just comments on his modesty. The two dissimilar men will now go on a spiritual journey that is similar in some ways to the one both the real Blake and the Native Americans took, and they will also try and elude the white men following them that Nobody can smell from their stench.

John Dickinson is upset that his son was gunned-down by Blake and that he also stole his prize pinto and while talking maniacally to a stuffed bear, he hires three notorious gunslingers as bounty hunters: the legendary cold-blooded killer Cole Wilson (Lance Henriksen), who supposedly “fucked his parents,” “killed them,” “cooked them up,” and “ate them;” and, the crazy talking Conway Twill (Michael Wincott), who sleeps with a teddy bear; and, a tough talking black youngster Johnny ‘The Kid’ Picket (Eugene Byrd), to go after Blake and bring him back–dead or alive.

Along the way Nobody tells William Blake after he recites to him some of Blake’s poetry from his Songs of Innocence, “Some are born to sweet delight, Some are born to endless night.” William Blake, he says, “you will learn to use your guns instead of words, your poetry will now be written in blood.”

On his odyssey, Blake will come across others who are trying to get him: it will include three deranged trappers — Big George Drakulious (Billy Bob Thompson), Jared Harris (Benmont Tench), and Salvatore Jenko (Iggy Pop), who wears a dress; then a racist Christian missionary (Alfred Molina); an ambusher who seriously wounds him again towards the end of his journey; and, finally two money-hungry marshals (Jimmie Ray Weeks and Mark Bringelson). They will all be killed by either Nobody or Blake.

The transformation of Blake comes when he takes peyote and sees things differently, no longer afraid of dying, he becomes connected Indian style to the nature of his surroundings. Nobody leaves him alone so that he can find out what his inner trip is without any diversions.

When the two are together again Blake is prepared for death, barely clinging to life, as Nobody takes him to spiritual friends among the Kwakiutl settlement and he passes through the hellish worldly sights for one last time. Having prepared for death by absorbing the teachings of Nobody–who tells him “death is like passing through the mirror,” Blake is now prepared to die in peace. He is placed in a canoe and sent out to sea to return to the spirit world he came from.

This is the kind of original film that you are not likely to see made by those box office watching Hollywood directors and those studio heads who wouldn’t know a real visionary work even if the real William Blake was to magically appear before them and shout his poems into their ears. Those magnificent Blakelike aphorisms are seamlessly dropped into the film. Nobody says, “The eagle never lost so much time as when he submitted to learn of the crow.” This fits easily into the flow and grace of this perfectly made film, where Nobody can say “You don’t stop the clouds by building a ship.” That could either be taken for an old Indian saying, or something Nobody made up, or one of Blake’s sayings from his “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience.”

The most remarkable aspect is not only that Jarmusch didn’t falsely romanticize the Western settler and idolize him for how good he was with a gun as most films foolishly do; but, he debunked that whole Western John Ford type of patronizing liberal myth that the cowboy was doing all that violence to advance civilization, that if the Indian can be civilized he can and should live with the white man. Those films left a lot to be desired even if Ford in his masterpiece “The Searchers” did tune in to the inherent racism in America; yet, he still couldn’t convey with the kind of depth what this film so easily manages to do — show how the Native Americans viewed the white man.

In this psychedelic Western Blake and Nobody are almost complete opposites, contraries if you will, borrowing from one of the bard’s adages of how best to gain wisdom. They enjoy each other’s company despite not knowing what the other is saying. Humor is sometimes a saving grace when all else fails and that is what is indisputably working here. What Jarmusch’s well-researched and historically accurate film was delving at, may not always be clear to some of the viewers; yet, what he is getting at is a poetical vision for America. The establishment critics, for the most part, dutifully lambasted this film because they said they didn’t get it even though they say that they laud the poetry of Blake. They said they still were confused by the film’s murkiness (I feel these are the same sorts that called Blake a madman in his lifetime and said his work was rubbish, and I am not surprised in the least at their negativity toward this original film).

The film had energy; and energy, Blake said, is ‘eternal delight.’ It also has a prophetic message for the modern technological age, and that message is that all is not rosy if we continue to destroy the planet and ourselves. It’s not that cool a thing to just shoot people as portrayed in so many popular action films, films that think they have to substitute action for imagination.

And as Blake wrote in Milton:

“Are here frozen to unexpensive deadly destroying terrors, And War & Hunting, the Two Fountains of the River of Life,Are become Fountains of bitter Death & of corroding Hell. Till Brotherhood is chang’d into a Curse & a Flattery By Differences between Ideas, that Ideas themselves (which are The Divine Members) may be slain in offerings for sin.”

REVIEWED ON 1/1/2000 GRADE: A+