CROSSFIRE

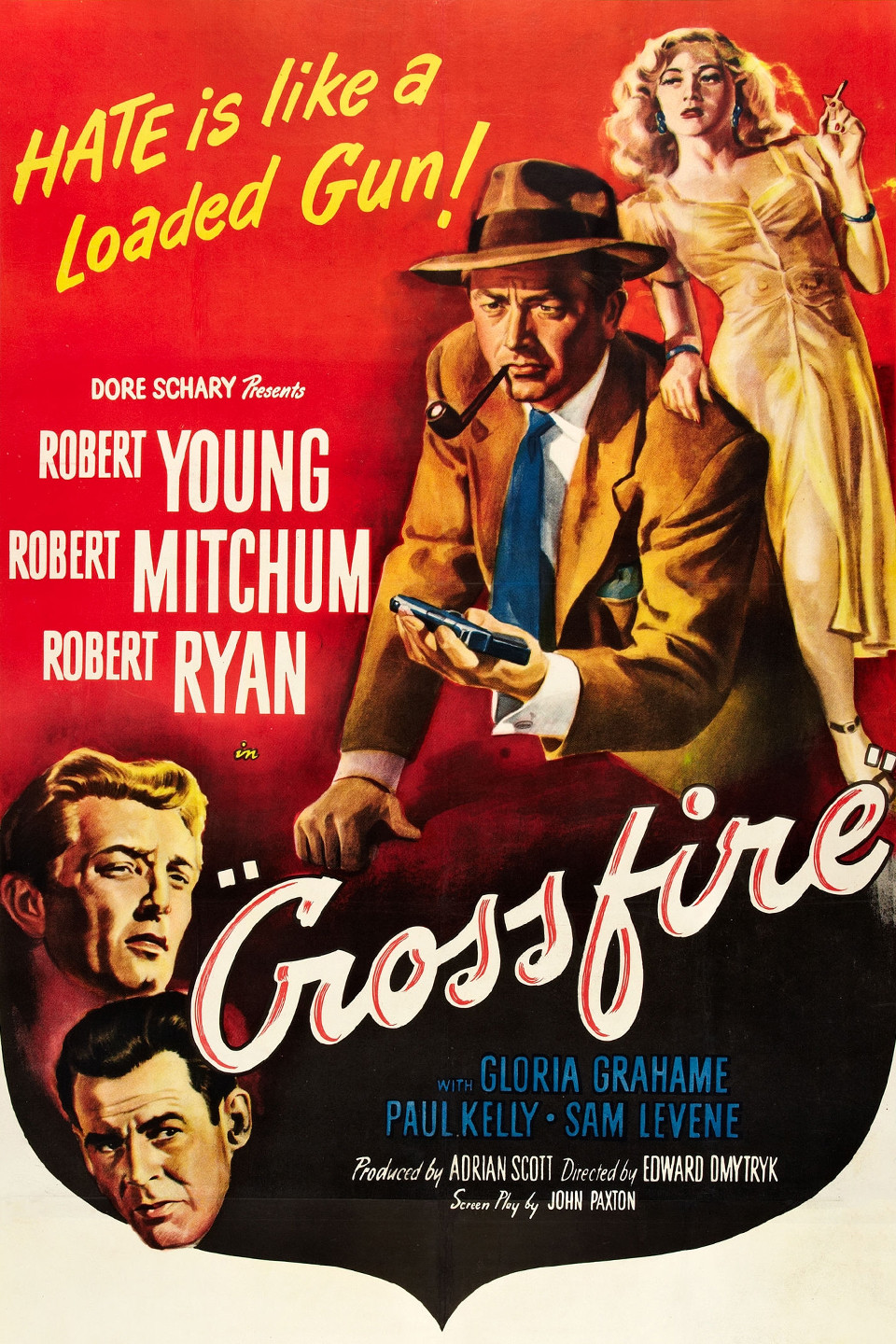

(director: Edward Dmytryk; screenwriters: from the novel “The Brick Foxhole” by Richard Brooks/John Paxton; cinematographer: J. Roy Hunt; editor: Harry Gerstad; cast: Robert Young (Captain Finlay), Robert Mitchum (Sgt. Keeley), Robert Ryan (Monty Montgomery), Gloria Grahame (Ginny Tremaine), Sam Levene (Joseph Samuels), Steve Brodie (Floyd Bowers), George Cooper (Arthur Mitchell), William Phipps (Leroy),Jacqueline White (Mary Mitchell), Marlo Dwyer (Miss Lewis), Paul Kelly (The Man); Runtime: 85; RKO; 1947)

“It would have been a much better film if it weren’t for the censor.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Warning: spoilers throughout.

This is more of a message film than a noir thriller, but has been classified by most cinephiles in the noir category. The story takes place right after WW11 in Washington D.C., as the soldiers of a Signal Corps outfit are being discharged from the army and returned to civilian life. Brooks’s novel broached the subject of a civilian getting killed by a soldier because he was a homosexual, but the Breen office that acted as a censor for Hollywood would never allow that topic. So the filmmaker made the bias crime against a Jew which also was a subject Hollywood tried to avoid but, perhaps, because of the Holocaust, it was allowed to be presented onscreen by the censor. Coincidentally, in the same year, there was another film on the same subject, “Gentleman’s Agreement,” but it confined the anti-Semitism to social situations. This B film is considered an experimental film and was budgeted for five hundred thousand dollars and shot in 20 days, and it spent most of its budget on its star cast and was rewarded with a box office success and was deemed with critically favorable reviews.

Robert Ryan just got discharged from serving in the marines. He had read Brooks’ novel and liked the book so much that he asked Brooks also a marine, to keep him in mind for the part of Monty if the book ever gets made into a movie. Brooks did just that when he was discharged from the service and was hired on as a screenwriter by RKO.

Four army buddies – a hillbilly Leroy (Phipps), a bigoted former cop in St. Louis Monty Montgomery (Robert Ryan), a redneck Floyd Bowers (Brodie), and a former WPA artist Arthur Mitchell (Cooper) – visit a bar while on leave. They strike up a conversation with Joseph Samuels (Levene) and his girlfriend, Miss Lewis (Dwyer). Mitchell is feeling despondent about being away from his wife and gets drunk but responds to Samuels taking an interest in what was bothering him. Mitchell was invited to Samuels’ apartment to continue the conversation, later on Floyd and Montgomery followed them and joined the party. Mitchell soon left because he wasn’t feeling well and didn’t want to be with Floyd and Monty. Monty, who appears in army khakis but with no army insignias, goes berserk when asked to leave and beats Samuels to death as the murder is seen on the shadows of the wall. The racial slur Jew boy is used by Monty, which emphasizes how this is solely a hate crime.

The police, under the investigation of Captain Finlay (Robert Young), find the wallet of Corporal Mitchell and suspect him of this seemingly motiveless murder. When they go to his army unit they talk to Sergeant Keeley (Mitchum-he sleepwalks through his inconsequential part). Keeley tells Finlay that he knows what type of person Mitchell is and that the soldier has been on a drunk binge recently, but he is no murderer. Keeley goes on to say Mitchell’s a gentle person, an artist. Keeley decides to find Mitchell before the police do. When he does, he listens to his drunken tale and what he did on the night of the murder. Keeley is convinced of Mitchell’s innocence and tells him to wait in an all-night movie. Keeley later sends Mitchell’s wife to meet him there. Mitchell tells her about going to bars and meeting a girl, and the couple seem to forgive each other for growing apart and are drawn close together again.

Crossfire becomes more of a film about anti-Semitism than it does a murder investigation, especially since there is no real mystery as to who did the killing. Finlay tries to explain the killer’s bias by saying, “Hate is like a gun.” He goes on to give a history lesson about prejudice in this country, about how his Irish grandfather was lynched because he was Catholic.

The script was stale, the acting was wooden by everyone but Ryan. Ryan was nominated for an Oscar, surprisingly the only time in his career. Gloria Grahame, also nominated for an Oscar has a leaden role as a dance hall girl, whose life is a mess but yearns for domesticity. There isn’t one character who doesn’t speak in clichés, except for Ryan. Paul Kelly had an interesting part as Grahame’s jealous divorced husband, but it didn’t have much to do with the story and therefore added nothing to it. Kelly’s original role was censored by the Breen office. He was supposed to be a john of Grahame’s, but that was too risque for the censors who didn’t want Grahame’s part to be that of a prostitute. They felt it wouldn’t look good to see soldiers frequenting a prostitute.

What this film should be commended for, is that it brought to the public’s attention that anti-Semitism can also be the subject of a hate-crime film. Hollywood films have a history of staying away from controversial subjects and this B- film did what other films didn’t at the time.

It is interesting to observe how this film got the ire of Senator McCarthy and his witch hunters. They called three witnesses from this film to their HUAC, but released Ryan when they checked out his war record. The producer Adrian Scott and the director Edward Dmytryk were accused of being Communists and were blacklisted from Hollywood for failing to testify. Both served time in jail and became known as part of the infamous Hollywood Ten.

J. Roy Hunt, the 70-year-old cinematographer, who goes back to the earliest days of Hollywood, shot the film using the style of low-key lighting, providing dark shots of Monty, contrasted with ghost-like shots of Mary Mitchell (Jacueline) as she angelically goes to help her troubled husband Arthur.

The weakness of the film is in the making of the psychotic Monty capable of not only killing Samuels but his best buddy Floyd, thereby diminishing the bias rage of the murder; it also implies bigots come only from the ranks of the ignorant, the lower-classes, and the mentally deranged. It also implies that the killer is so crazed that he will even kill one of his own kind, and therefore a bias killer is really only a psychopath. Under pressure from the censors, the filmmakers weren’t allowed to explore any further the depths of anti-Semitism.

It should, also, be noted that both Dmytryk and Paxton received Oscar nominations.

The ending seemed disjointed, as Monty is fooled by his sidekick Leroy into falling for a police trap. The Southerner had to be talked into betraying Monty by a lecture on prejudice given by Finlay. When the trapped killer escapes from Finlay, the nonviolent policeman is forced to gun him down in the street. What was even stranger was the liberal Keeley walking away from that shooting with his arm around the reactionary Leroy, telling him he did right, as they walk the dark Washington streets looking for a place to get some coffee. The censors demanded that it is not in the best interest of the War Department to show that the soldiers were always drinking alcohol. Even though the filmmakers were forced by the Breen office to bend over backwards to make their film a safe one, it still showed the bias present in America and how serious a problem it was.

It would have been a much better film if it weren’t for the censor.

REVIEWED ON 2/18/2000 GRADE: B

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DENNIS SCHWARTZ