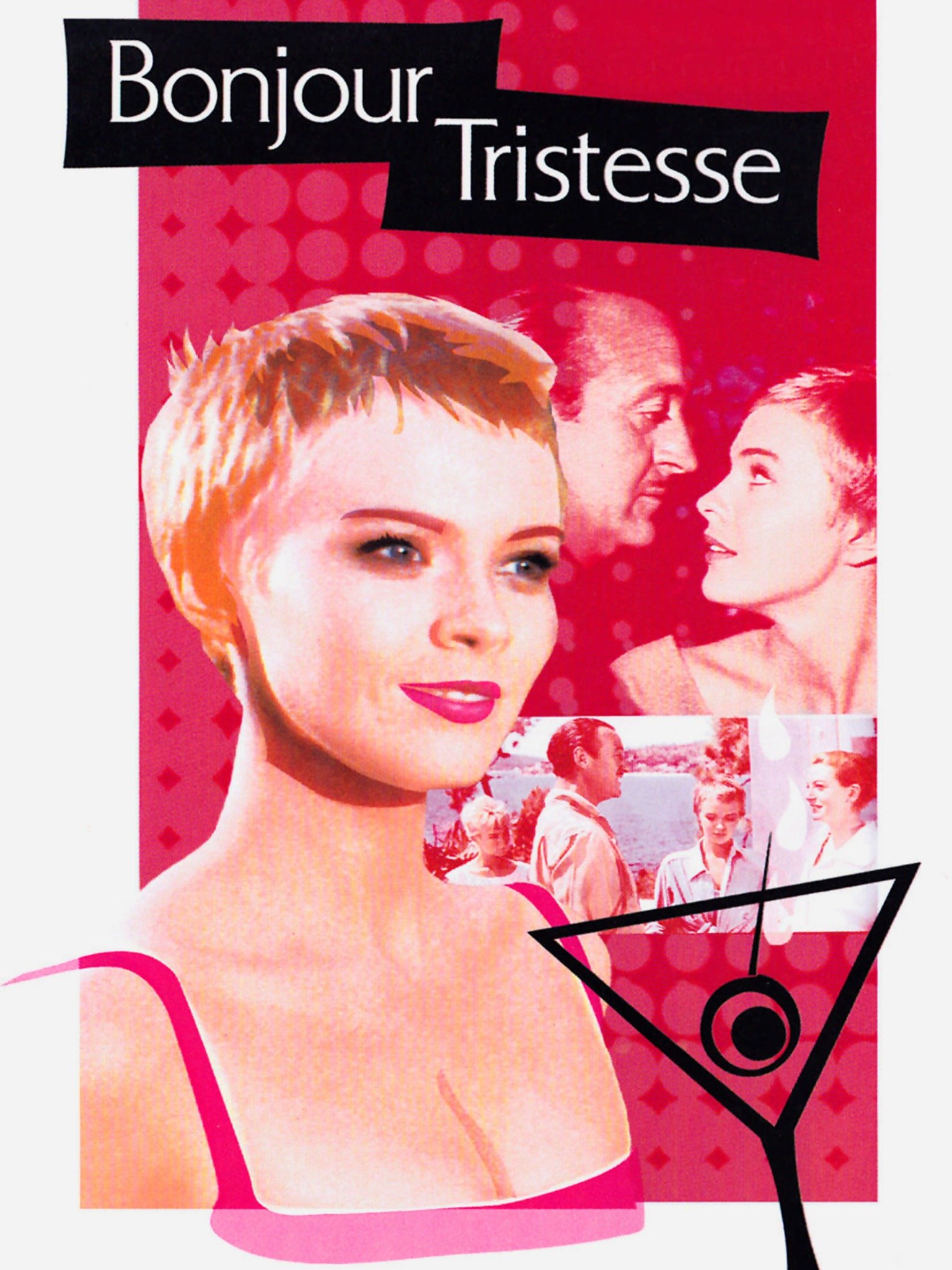

BONJOUR TRISTESSE

(director: Otto Preminger; screenwriter: from the novel by Francoise Sagan/Arthur Laurents; cinematographer: Georges Perinal; editor: Helga Cranston; music: Georges Auric; cast: Deborah Kerr (Anne Larson), David Niven (Raymond), Jean Seberg (Cecile), Mylene Demongeot (Elsa), Geoffrey Horne (Philippe), Martita Hunt (Philippe’s Mother), David Oxley (Jacques), Walter Chiari (Pablo), Jeremy Burnham (Hubert, Artist), Juliette Gréco (Herself, Nightclub singer; Runtime: 94; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: John Palmer/Otto Preminger; Columbia Pictures; 1958)

“Has a glacial tone that gets covered with a lobster red French Riviera sunburn.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

It’s based on lesbian author Françoise Sagan’s 1955 novel “Bonjour Tristesse,” which tells about the amours of a wealthy and hedonistic Parisian bachelor father, Raymond (David Niven), living for the summer in a rented villa on the French Riviera with his free-spirited and materialistic-minded mistress Elsa (Mylene Demongeot) and amoral and very much attached to him 17-year-old impressionable daughter Cecile (Jean Seberg). There are thinly veiled hints to incest in the father-daughter relationship, but with no overt signs. The wicked romantic melodrama is stylishly filmed, as it veers between the present shot in a wintry black-and-white and the flashbacks in a lush summery Technicolor; the overall effect has a glacial tone that gets covered with a lobster red French Riviera sunburn.

Autocratic director Otto Preminger (“Exodus”/”The Cardinal”/”Laura”) casts once again his discovery of Jean Seberg as star, as if thumbing his nose at critics who panned her debut in the commercial flop Saint Joan. In this follow-up film Jean received much better reviews in the States and raves in France, as Godard was so impressed he cast her in Breathless based upon her performance in Bonjour Tristesse and she became an international star in that New Wave smash hit. The story is told from the teenage Cecile’s point of view. Arthur Laurents turns in the screenplay that is strangely entertaining in its cruel moments.

Cecile, who is drifting into being a female version of her frivolous playboy father, tells in flashback about her eventful last summer on the French Riviera with her father and his newest mistress, Elsa–as the trio hit the nightspots and gambling casinos and were living carefree for the moment. The three were as happy as larks, but things took a turn when Raymond invited Cecile’s late mother’s uptight, sexually repressed friend Anne (Deborah Kerr), Cecile’s godmother, to spend her summer holiday with them and she surprisingly accepted even though knowing their bohemian lifestyle was opposite her conventional lifestyle. Anne is a successful Parisian fashion dress designer, who will not go to bed with Raymond unless he marries her. To Cecile’s chagrin, after a bumpy start, Raymond is so keen on Anne’s slender body that he becomes engaged to her and dumps the much younger Elsa. The abandoned Elsa departs with a rich South American admirer named Pablo. Bossy, prudish and prissy by nature, Anne now the domineering force in the villa becomes a killjoy to Cecile by first breaking up her relationship with nice college law student next door neighbor Philippe (Geoffrey Horne), challenging Cecile’s aimless life and then insisting Cecile study to pass her philosophy exams she previously failed. To exact revenge for these slights, Cecile concocts a devilishly childish scheme to break up the relationship between her dad and Anne. It works better than expected, and a distressed Anne feels betrayed by Raymond when she catches him making love in the woods with his former lover Elsa. Anne bolts from the Riviera in her car and is later found at the bottom of the sea, in what was called an accidental death. Father and daughter know it was suicide, but fail to say that as they read each other’s thoughts to not talk about that tragedy. Next summer they plan to vacation in the Italian Rivera and continue to live their usual hallow life.

The film suffers because all the main characters are unsympathetic and shallow figures, and it’s hard to really care what happens to any of them. In the final scene Seberg sits at a make-up table, gazing at herself as she applies cold cream to her face and appears expressionless and very much alone. Her story ends on this sad note. Aside from the English Niven and Kerr being impossible to believe as French and the film’s glossy soap opera feel, there’s a certain unhealthy but tasty appeal in Seberg’s uneven performance where she appears angelic but nevertheless shows a capacity to be cruelly destructive when she doesn’t get her way. Her bitchy attitude (her best acting) gives the film a bewitching charm that I think truly captures Sagan’s heroine and speaks to a class of idlers who are very well captured on film in a nonjudgmental way as devouring soulless egotists.

REVIEWED ON 12/16/2007 GRADE: B