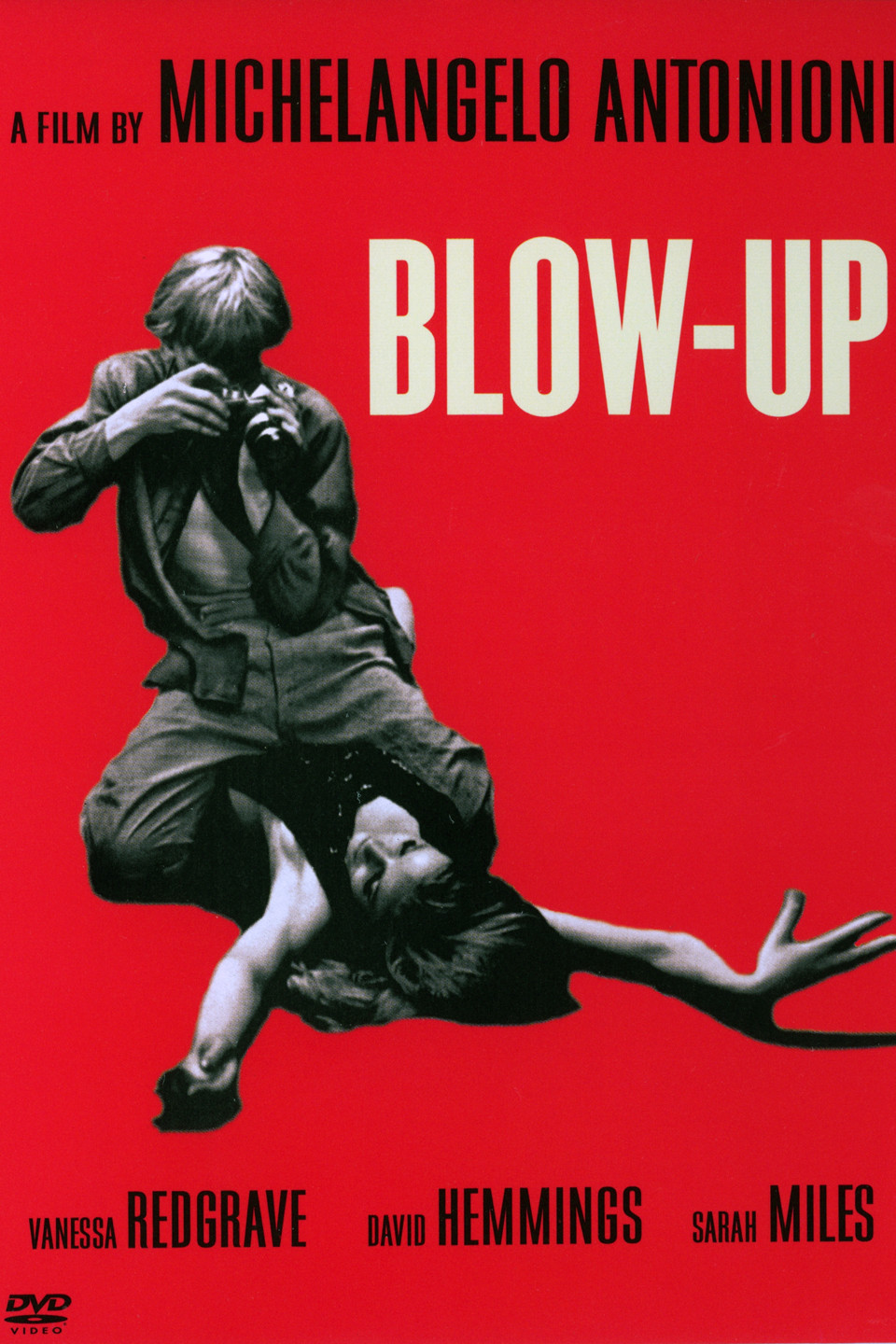

BLOWUP (director/writer: Michelangelo Antonioni; screenwriters: from the short story Las babas del diablo by Julio Cortazar/Tonino Guerra; cinematographer: Carlo Di Palma; editor: Frank Clarke; music: Herbie Hancock/The Yardbirds; cast: David Hemmings (Thomas), Vanessa Redgrave (Jane), Sarah Miles (Patricia), Peter Bowles (Ron), John Castle (Painter), Jane Birkin (Blonde Girl), Gillian Hills (Brunette Girl), Verushka von Lehndorff (Herself); Runtime: 102; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Carlo Ponti; MGM; 1966-UK/Italy)

“A fascinating take on the mod lifestyle.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

The great Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s (L’avventura – 1960/La notte -1961/The Eclipse -1962/ Red Desert -1964) first English-language film is set in the “Swinging London” of the Sixties. It’s lifted from the short story “Las babas del diablo” by Julio Cortazar. Tonino Guerra is cowriter with the director. This seminal film of that era, one of the most influential and a true voice of inspiration to an upcoming group of innovative new directors across the world, is a fascinating take on the mod lifestyle. It offers an unvarnished look at casual sex, pot smoking, a rock ‘n’ roll club concert with The Yardbirds, street mimes as pranksters and, if you will, yuppie consumerism. The arthouse film caused controversy over its nudism and as to whether it was a pretentious work or a groundbreaking artistic cinematic work. I wouldn’t worry about that debate and would just take in the accurate reflections of the mood it set and the gorgeous photography of every scene. It’s a truly wonderful pic as spectacle and conveyor of a new society in action, one that is surprisingly not outdated in its observations as were many other praised films of that time frame.

Antonioni examines changes in society through the lenses of the joyless, wealthy, trendy, empty-headed, petulant, asshole fashion photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) and his aimless existence of soaking up the scene’s decadence and boredom; the film also moves into mystery thriller territory upon the discovery of a possible murder. Ultimately Antonioni’s purpose is to bypass the shallow undertakings of the mod trend-setters featured and create a metaphysical debate if there’s really a difference between fantasy and reality. Fortunately this doesn’t happen till the last ten minutes; so much of the film remains as enjoyable as a stroll in the park on a nice day.

The metaphysical deep part of the pic questions if the truth can be ascertained in a photograph. In this abstract examination of logic, the lines between subjectivity and perception are blurred even with the proof of a photograph. For those expecting a thriller with a payoff, they will be disappointed–Antonioni had more esoteric concerns in mind.

The film trails Thomas around in a hectic day of his life. He first comes across a jolly van load of street mimes while riding in his Rolls Royce convertible. At his photography studio he does an energetic photo shoot with model-extraordinaire Verushka; he later comes across peace demonstrators in the street, frolics with two air-head groupy wannabe models who invade his flat, and impulsively buys a huge airplane propeller in an antique shop that is beautiful but useless. Thomas then takes a break from his busy schedule to stroll in the park and take spontaneous photos for a photo book he’s working on with his editor Ron. There he snaps a series of photos of a gray-haired well-dressed middle-aged man and a woman embracing. The woman, Jane (Vanessa Redgrave), anxiously runs over to get the negatives but Thomas refuses. The woman surprisingly finds him at his studio, and offers money and then her body for the negatives. He gives her a phony roll. On developing his picture he finds what might be a man with a gun in the bushes and, after enlarging the negative, a body. When he goes back to the park late at night he finds the body, but since there was no evidence of foul play he doesn’t think it necessary to report it to the police–probably not caring enough about the corpse to get involved. After visiting a stoned Ron at a pot party and finding it not possible to communicate with him about the possible murder, he returns to the studio and all his pictures have disappeared. Returning to the park in the morning the body, too, has disappeared. The film ends with the same street mimes from the opening shot appearing at the park to play an imaginary tennis game.

With the murder tale payoff no longer possible as a result of the evidence disappearing, the film instead resolves as a moralistic parable. What hasn’t vanished is the soulless, emotionally stifled and uncaring Thomas, whose success and wealth still leaves him as a desperately lonely and sad individual whose slim chance of finding the truth or inner bliss is through his art–the only thing he still loves with a passion. His only real joy was in working on the photographic blowups, trying to see if his skills would detect the answer to the puzzling shots–caring more about his craft that any of the people involved in the incident.

REVIEWED ON 6/14/2005 GRADE: A

Dennis Schwartz: “Ozus’ World Movie Reviews”

© ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DENNIS SCHWARTZ