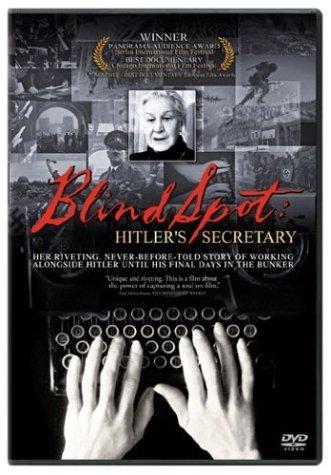

BLIND SPOT: HITLER’S SECRETARY (Im toten Winkel – Hitlers Sekretärin)

(director/writer: André Heller/Othmar Schmiderer; cinematographer: Othmar Schmiderer; editor: Daniel Poehacker; cast: Traudl Junge; Runtime: 87; MPAA Rating: PG; producers: Danny Krausz/Kurt Stocker; Sony Pictures Classics; 2002-Germany, in German with English subtitles)

“Another testimony about the banality of evil.“

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Hitler’s secretary Traudl Junge, who served that post from 1942 until the end of the war, gives her first extensive interview about her days with Hitler to Austrian video filmmakers André Heller and Othmar Schmiderer. It took place between April and June of 2001, when she was an 81-year-old. The secretary died later that year in February, after a long battle with cancer, on the night the film premiered in Berlin. The well dressed, articulate and almost emotionless Junge tells about how she was handpicked, when single and 22, to be one of the Führer’s secretaries at the Wolf’s Lair (his field headquarters in East Prussia) and also served at his bunker in Berlin, where her job required just taking dictation.

In this no-frills documentary, Junge is the only voice heard as she talks into the camera and there’s only a single-camera shot of her. She spins her rationalizations for being a believer and how easy it was in her insulated world not to know the truth, as she sounds like so many other Nazis following the line that they were just doing their duty (though she was never a party member and like Hitler’s main squeeze Eva Braun they claim to be apolitical). Junge tells a lot of little details and meaningless anecdotes about life in the bunker with Germany’s main man, whom she regarded as a kindly father figure (important to her because she was raised by her divorced mother and tyrannical general grandfather). She further reveals that Hitler was not animated like seen in his public speeches, and it impressed her greatly that Hitler was always very gentle to her. She goes on to tell about some of Hitler’s quirks such as liking cold rooms, hating flowers in his room and being touched. Hitler is pictured as an idealist who didn’t care about humanity–the cause superseded everything else–as she mentions he never dwelt on the loss of lives or bombed out cities in Germany as the war progressed. He only stated that Germans should not be mawkish and should do their duty. She continues that Hitler never spoke about the Jews in her presence, though he got angry when someone once mentioned their mistreatment and was never invited back. It’s also revealed that he was in good health except for digestive problems treated by his personal physician, Dr. Morell, a believer in holistic medicine, with pills and regular injections.

Junge admits that she believed in his promises to create a better world and of how corrupt the rest of the world was, and if Bolshevism wasn’t stopped by the Nazis no other country in the west could. We learn also of Hitler’s affection for his German shepherd Blondie, who pleased him greatly because she obeyed his every command and could do tricks. Of course, this didn’t stop him from poisoning the dog when he felt betrayed by Himmler and wanted to see if the cyanide given him worked. After trying to make Hitler look human, she pleads her case of being young, innocent and ignorant of her man’s evil designs. The filmmakers give her a chance to look back at what she said on a monitor and she becomes more self-critical and expresses guilt feelings about being unaware of the Final Solution. She looks back at that time with disgust for not being more aware, critically comparing herself to a classmate—a girl her own age—who was merely derogatory of the Third Reich and as a result was executed. Her last words to the directors are “I think I’m beginning to forgive myself.”

I felt neither rage nor pity for Hitler’s favorite secretary who cemented this honor when she married in 1943 one of Hitler’s servants, he was killed in action in 1944. In one breath she pronounces herself guilty of complicity and in the next believes in her innocence because Hitler betrayed her by being a liar and abandoning her through suicide in her time of greatest need at the end of the war. It is sad to think, but I can’t help feeling she behaved much like I would expect most members of the American silent majority would if they were in similar circumstances.

The documentary plays as the usual stuff heard from those involved with the Nazi madness, another testimonyabout “the banality of evil.” At one point she says Hitler was a war criminal, but I just never realized it. Hitler’s favorite secretary tells about regularly eating lunch or dinner with the Führer, as he preferred the awed secretaries at his side than his military staff talking about the war. He took turns dining with the four bunker secretaries by having two of them at his table during these times. Junge mentions another tidbit about Hitler, as she found it odd that he never talked about love. Even his relationship with Eva Braun was viewed by the secretary as not an erotic one.

Junge’s most interesting revelations were about the last days at the bunker and how confusing they were and how morbid it was that everyone was talking about suicide. Before Hitler’s suicide and after his last hour surreal marriage to Eva Braun, which she attended, she was called in take down his last dictation called “My political testament.” Hitler went through his usual hateful diatribes and left her disgusted that in the end he had nothing important to say. This documentary also had nothing major to say but it remains interesting because it sheds some more light on one of the most despicable monsters to ever exist, as he’s depicted how he acted in private as only an intimate would know.

REVIEWED ON 11/26/2003 GRADE: B-