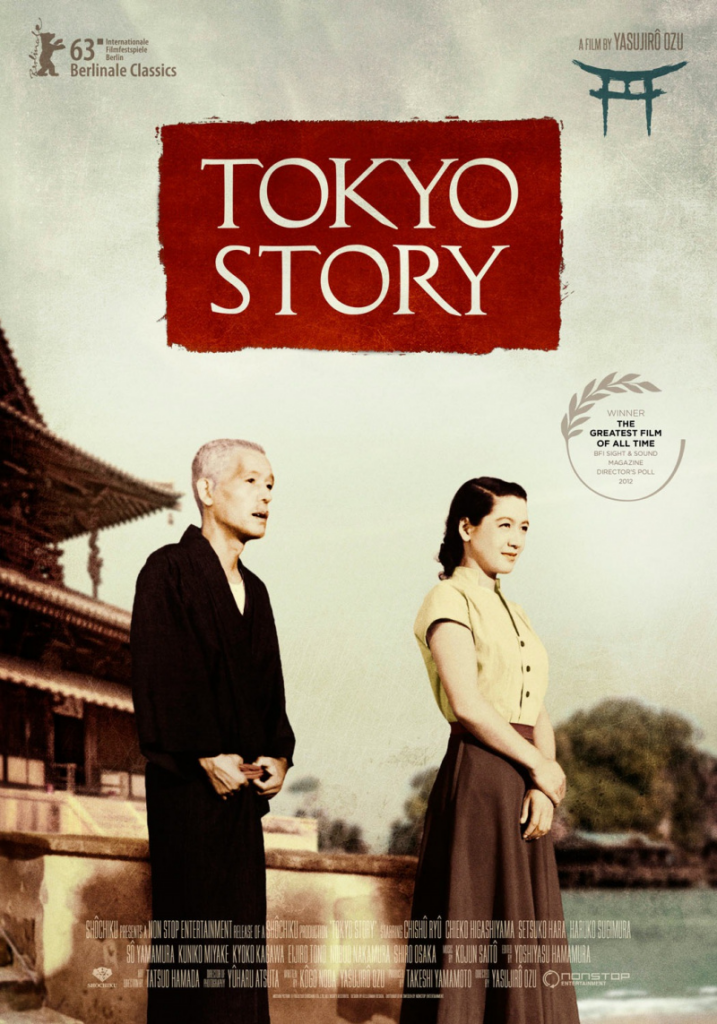

TOKYO STORY (Tokyo monogatari)

(director/writer: Yasujiro Ozu; screenwriter: Kôgo Noda; cinematographer: Yuharu Atsuta; editor: Yoshiyasu Hamamura; music: Kojun Saitô; cast: Chishu Ryu (Shukishi Hirayama), Chieko Higashiyama (Tomi Hirayama), Setsuko Hara (Noriko), Sô Yamamura (Doctor Son, Koichi), Kyôko Kagawa (Kyôko), Haruko Sugimura (Shige Kaneko, Beauty Salon Owner), Eijirô Tono (Sanpei Numata), Nobuo Nakamura (Kurazo Kaneko), Hisao Toake (Osamu Hattori), Zen Murase (Minoru), Mitsuhiro Mori (Isamu), Kuniko Miyake (Fumiko), Shiro Osaka (Keizo); Runtime: 136; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Takeshi Yamamoto; Criterion; 1953-Japan, in Japanese with English subtitles)

“This very well might be the best film ever made.“

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

For a Westerner to watch a Yasujiro Ozu film is to have a totally different film experience than conditioned by Hollywood. Ozu’s films were greatly appreciated in his country, but in the west have reached critical acclaim with only select audiences. Don’t expect an action or sentimental or special effect film, or one with fancy camera movements, fades, dissolves, pans or tracking shots. Ozu turned out powerful and beautiful and emotionally gripping films, mostly in b/w (his first color film was in 1958), and never made one that lacked a lyrical quality. In Japan, he was considered the most Japanese of all the national directors. His scenes were shot in 180-degree cuts and in a circular 360-degree space, which made for dramatic visual effect. Ozu is the master of using space as poetry. His camera is always still and he never uses low angle shots, as the camera remains positioned about 3 feet off the ground. That corresponds with the eye-level of an adult sitting on a meditation cushion, as is the customary way for the traditionalists to be seated. He’s also fond of trademark shots, such as a train pulling into a station and shots of emptiness, where he waits for his characters to walk into that space. His emptiness represents the Buddhist eternal no-thing-ness and the characters represent the temporary concerns of this world, that include their life long attempts to wrestle with living a full life and its disappointments. The characters through their personalities become the central figures of Ozu’s profound vision, while their stories remain almost entirely undisturbed by any extras or need for stylization. The master director made 54 films in his long career before his death from cancer in 1963, at age 60.

Tokyo Story is reputed to be his favorite, and is the best known of his films in the States because it was more widely distributed than his others. In my way of thinking, one could not go wrong to use Ozu as a measure or a model against other filmmakers. He might arguably be the best filmmaker ever. But, if not, he’s certainly one of the best and despite his attention to Japanese lore he still has a universal appeal. His perfect films, even if not thought so by those demanding a more flashy storyline and gloss, are standards for that art form just like Charles Dickens is for literature, Goya for art, Milton for poetry, and Beethoeven for classical music. These are all artists who can reach both a wide democratic and an elitist high-brow audience, as there is an entry level to their work at all stages.

Tokyo Story opens as an elderly middle-class couple Shukishi and Tomi Hirayama (Chishu Ryu & Chieko Higashiyama) are leaving their sleepy traditional seaport town of Onomichi to visit in Tokyo two of their children, their eldest pediatrician son Koichi (Sô Yamamura) and their next oldest beauty salon owner daughter Shige Kaneko (Haruko Sugimura), who are a day and half away by train. They have lost contact with their successful career-minded children, and since the couple is getting up in the sixties they are interested in seeing them again before it’s too late and also seeing how bombed-out Tokyo has been rebuilt since the war. They leave their youngest daughter Kyôko, a school teacher, at home, and meet their busy youngest son Keizo in Osaka at the station as the train makes a brief stopover.

Their doctor son lives on the outskirts of town and is a neighborhood doctor with a busy practice, but not the big-shot physician they assumed. Their two grandchildren, Minoru and Isamu, are emotionally unreachable. Minoru squawks that he has no place to study with their visit, while their father gets called on an emergency and can’t show them the town on Sunday–his only day off. The wife can’t leave the children alone and they’re so concerned with money that they can’t spring for a babysitter, so the grandparents remain home-bound. Soon the doctor palms his parents off to his sister’s house, but she proves to also be too busy to take them out. She’s also more overtly selfish, as she chides her husband (Nakamura) for buying expensive cakes for them and sees to it that they don’t get it as she stuffs them down her throat before they arrive. Shige asks their daughter-in-law Noriko (Setsuko Hara), who married their oldest and has been a widow for the last 8 years when he died at war, if she can take the parents out. Noriko is really glad to take them out and gets permission to take the day off from her office job–the only host who bothers to take a day off. She’s the poorest and not a blood relation, but she makes the time to show them the typical tourist sights and doesn’t have a selfish bone in her body though she thinks she has some selfish faults that don’t show like forgetting occasionally about her dead husband. The parents apologize to her for the inconvenience, and while thanking her for being so generous and honest they let her know that their son was far from perfect and she must have had some difficult times with him.

Shige plots with her brother to chip in and dump the folks in Atami, a hotel hot spa mainly catering to the younger generation but not that expensive, as the two selfish children are more interested in their careers than in seeing their parents. The grandparents find the place noisy and can’t sleep and decide to go home tomorrow, but when they return to Shige’s to stay for the night they are not welcomed back because she has some beauticians meeting over the house and is too embarrassed of her folks to be seen with them. Feeling homeless, the parents kill time in Ueno Park and wait for Noriko to get home from work. Mother stays with Noriko and takes heart in the kind-hearted daughter-in-law, and in a genuine way urges her to remarry. Her happiest time in Tokyo is this night visit with Noriko and their refreshing heart-to-heart talk. Meanwhile Father goes out at night with Hattori, a resident of Onomichi who moved here 18 years ago. The two old time drinking buddies haven’t seen each other since, and meet another transplant from their hometown and get stinking drunk while they reminisce. Hattori also talks about his disappointment with life and his children, but Father doesn’t blame the children for his disappointment in them saying that’s life. He looks on the positive side that they’re better than most children. When the drunks leave the bar a policeman takes Father and Hattori back to Shige’s house to sleep it off, and the drunken parent is reprimanded by his nasty daughter for straying again into drink. The next day the grandparents go home, but on the train Mother gets sick and when they reach home she’s bed-ridden in a coma. All the children and Noriko come for the death-vigil, but the son in Osaka delays the visit for selfish reasons and arrives after she died. Shige is the first to cry openly, but the tears seem to be both sincere and for herself–as one can’t get past her selfish nature even when she cares. At the Buddhist funeral, the chants get on Keizo’s nerves and he exits unable to face his guilt for ignoring his mother all his life. All three children make a quick exit after the funeral, with Shige shamelessly making off with some of her mother’s clothes. Only Noriko stays behind and keeps the lonely Father company, as he greets a gorgeous sunrise–signaling a new day but still another hot one. Father and Noriko share a beautifully tender scene together as he presents her with Mother’s wristwatch–which greatly touches her and links Mother and daughter-in-law with a well-earned feminine wisdom.

There’s hardly a story or much to decipher psychologically, but everything is so real that you feel part of the family and relate to the unforgettable characters as if they were perhaps your family or friends or neighbors. You are drawn to their mundane everyday lives, subtle gestures of kindness, and daily rituals. There’s even a few comic moments thrown in, like all the passenger heads bobbing up and down in unison while on a sightseeing tourist bus ride through a bustling Tokyo. All the film’s greatness is in getting even the smallest of details exactly right and in the overwhelming emotional pronouncements, and in the compassion Ozu shows for all the characters. It’s a sad story about the end of the older generation, a generation that has passed out of favor due to the new industrialization and the way the modern houses are built without the need for meditation rooms to relieve the stress. The transitional generation, represented by the selfish children, has gone through great change brought on by the lost war. That generation is already distant from the generation to come represented by the estranged grandchildren growing up in a world of industrial smoke stacks and skyscrapers and need to learn English. Their world no longer resembles the world of their traditionalist grandparents or hardworking parents, but beckons to an unknown future that is represented by all the clicking sounds from the clocks marking off the rapid passing of time. There’s no American multiplex showing a similar family-styled melodrama that can match this film for intensity and breath of scope and honesty of character. This very well might be the best film ever made, as this review only skims the surface of its depths. In a 2002 Sight & Sound international critics’ poll, Tokyo Story was ranked as one of the ten greatest films ever made.

REVIEWED ON 12/9/2003 GRADE: A+