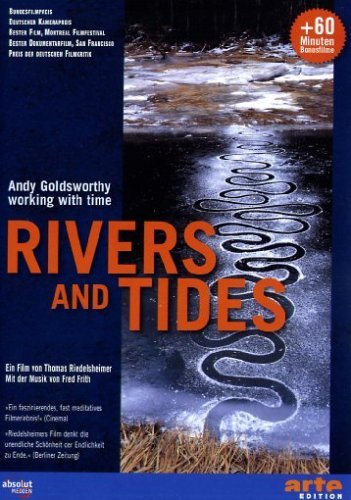

RIVERS AND TIDES

(director: Thomas Riedelsheimer; cinematographer: Thomas Riedelsheimer; editor: Thomas Riedelsheimer; music: Fred Frith; cast: Andy Goldsworthy; Runtime: 90; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Annedore V. Donop; Roxie Releasing; 2001)

“It’s a film for those who want to see an artist unobtrusively seeking enlightenment.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A sparkling minimalist art documentary that profiles the grey bearded, 46-year-old, renown Scottish sculptor Andy Goldsworthy and his theme of “Working With Time.” For the ebullient, soft-spoken, iconoclastic Andy, life is bubbling over with energy and art is his nourishment. German filmmaker Thomas Riedelsheimer’s mind-expanding contemplative film, in which he worked for over a year with Goldsworthy, won the Golden Gate Award Grand Prize for Best Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Andy narrates and describes his creations, expressing his need to understand nature. He demonstrates how there’s life even in dead objects by grinding an iron-rich stone and finding a red powder inside, which is similar to the blood in the animal world when he tosses the particles into a stream and we see it flowing. Andy puts in a lot of effort to create his trademark huge stone pine cones, one by the ocean and the other in a field. They are fragile works that depends on everything being balanced, and for them to appear as if they were effortlessly created.

Andy travels to Nova Scotia to work with ice, driftwood, and snow; in the Storm King Arts Center in Mountainville, N.Y, he creates a winding stone wall built to last; at the Digne Museum in southern France he creates a clay wall; and, in his hometown of Penpont, Scotland, where he’s most acclimated to the changing conditions, he works with bracken, dirt, grass and leaves. He documents his impermanent work with photographs. For the most part, his creations are temporary, as nature takes them back to their sources and breathes new life into them. In one case, a rising tide unearths his circular driftwood arrangement in a Nova Scotia salmon hole and returns it to its river source. The beauty is in the pleasure of creating and not in its permanence. One either gets what he’s doing, or doesn’t. In a way it’s a spiritual quest, much like the Tibetan lamas who create sand mandalas only to soon discard them. It teaches the impermanence of the materialistic world and the permanence of the spiritual, and how there’s a harmony in nature that one can tune into to gain peace of mind.

The film’s focus is entirely on this unique artist and his visions. His work is his life. It gives him the energy to relate peacefully in his stone house with his wife and four youngsters, his local acquaintances, and with the world. The artist seeks a quiet and civilized life, one that allows him to fit into his environment. He rises, at times, as early as 4 am, and instinctively goes out to the field to gather whatever is available to work on his next project. That Andy is not only an inspiring artist but a fine human being, certainly helps us look kindly on this film. It’s an enthralling look at a playful artist at work, who is not afraid to allow us to look over his shoulder and even see some of his goofs. The Goldsworthy earthworks, which is what he calls his art, are beautiful to behold. The film is a meditation on life that reaches the heart, where no words can adequately describe all that the artist is doing. Also, the gentle music by Fred Frith adds to the overall warmth. It’s a film for those who want to see an artist unobtrusively seeking enlightenment. The artist is letting us know what he thinks is important in this modern world of many diversions.

REVIEWED ON 5/11/2003 GRADE: A