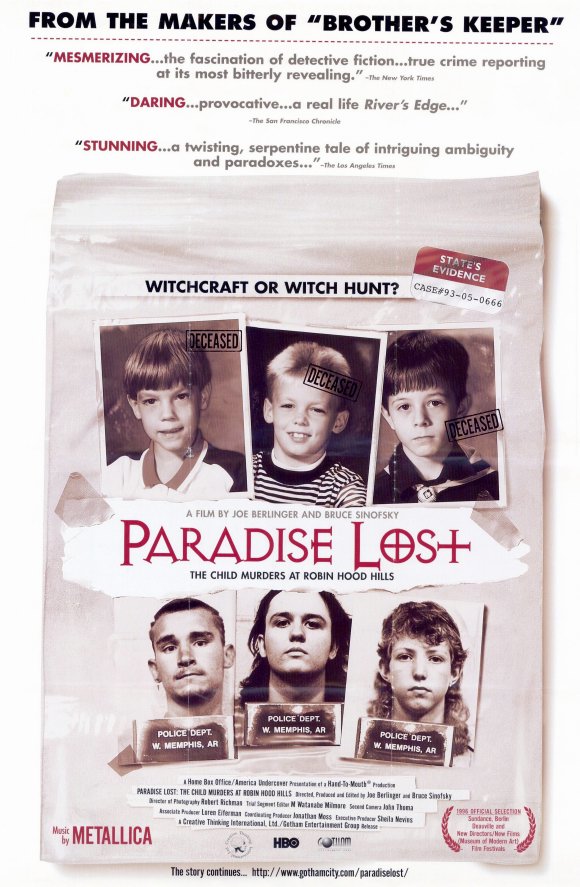

PARADISE LOST: THE CHILD MURDERS AT ROBIN HOOD HILLS

(directors: Joe Berlinger/Bruce Sinofsky; cinematographers: John Thoma/Douglas Cooper/Robert Richman; cast: Damien Wayne Echols, Jason Baldwin, Jessie Miskelly; Runtime: 150; MPAA Rating: NR; Creative Thinking International; 1996)

“Should give you food for thought about how unfair the judicial system can be for those who are poor.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

In the documentary Paradise Lost the truth is played out in earnest without actors or script, just by those involved in the courtroom. The film goes into gross detail describing the horrific murders of the three second-graders: Christopher Byers, Steven Branch, and Michael Moore. Their mutilated bodies were found on May 5, 1993, in a wooded area near West Memphis, Arkansas, which the locals call Robin Hood Hills. The film records the trial of the three teens accused of this crime, whose motive the prosecutor attributed to them was that they were in a satanic cult.

Crime is as American as apple pie, and unfortunately bizarre murders are not that uncommon on the American landscape. But when the victims are three innocent 8-year-olds, emotions naturally run high. There is a public outcry to get the killers and either execute them or give them life sentences, as we look at ourselves and ask who could do such a thing and why. We also want those who did it caught as soon as possible. We want to see how our criminal system works: from police, to prosecutors, to lawyers, to judges, and to jury. Most of us have formed an opinion on how we think the system works, and most of us realize that statistics of arrests and convictions do not tell us the whole story. It is not until we see an actual trial do we sense how delicate a system we have; how in the hands of forthright, honest, intelligent, and fair-minded participants, the system should work fine; but, if that is not so, we better watch out, the system can backfire and make us scratch our heads and wonder if it is possible for justice to work. And that is what this objective documentary does, as it allows us into the courtroom to see how the participants do their job.

For some reason there is a separate trial for Jessie Miskelly, the pint sized 17-year-old, who has an IQ of 72 and speaks in a slow and deliberately awkward manner. He seems less intelligent than even that low score indicates and is the one the police picked up and questioned after a month of mounting pressure that they have bungled the case. They get a confession out of him without a lawyer present after he, at first, denied doing the crime. In his flimsy confession where he does not even accurately state what has happened, he goes on to implicate two other friends in the crime: the meek and mentally deficient Jason Baldwin and the more intelligent and articulate Damien Wayne Echols, who antagonizes the small-town by being into heavy metal music played by his favorite group Metallica. It is also discovered that he borrowed a library book on a witches movement called Wicca (white magic), which he says he only read about and does not practice. He also antagonizes most citizens of the town by dressing in black, which his father caustically comments “Even Johnny Cash wears black.” In other words these three friends, who were not interested in sports and appeared to be different in temperament and attitude from the rest of the town, were looked upon with hostile suspicion even before the crime.

The filmmakers spent a lot of time with Jessie’s family and with the lawyers defending him and going over his confession, which Jessie now says is not true. All of the lawyers come to the conclusion that Jessie was a frightened boy, who just gave that confession to get out of the police line of questioning. He supposedly has an alibi for when the murders took place — but the filmmakers did not reveal what his alibi was or for that matter what the other accused boys’ alibis were, for a reason I cannot understand. In any case, there is nothing to link Jessie to the crime except for the dubious nature of the confession. There is absolutely no physical evidence of any kind at the crime scene, even though all the victims bled and one lost 5 pints of blood while bleeding to death. It is unlikely that Jessie and his passive friends would have been able to do the crime, notwithstanding that they had any reason to do it; and, for them to be so cool about it after the crime and also be so thorough in covering up any evidence, seemed a reach. Just seeing them and hearing their story and seeing no solid proof put forward except for innuendo and a coerced confession, is not what I call having a solid case against them.

Jessie was found guilty and given a life sentence plus 40-years even though in his bogus confession he claimed not to have murdered anyone, he just held down the Moore boy for the others to kill. It was made apparently clear that the police and the prosecutor were not looking for any reason to exonerate these three from the crime. These rational men, defenders of the law, seemed self-satisfied with the job they were doing. The job they did frightened the heck out of me because of their unwillingness to check everything out; and, as much as the crime revolted me, this revolted me with almost equal disdain.

We also see a hair-raising bit of unexpected melodrama from John Mark Byers, stepfather of one of the victims, as he is caught on videotape re-creating how he thinks the murders took place and then calling on God for vengeance. This guy was more frightening to watch than the three accused of the crime, and indeed the defense team suspected him of doing the crime. But since the police refused to really question this guy seriously, our only contact with him is when he talked freely into the camera. He volunteers the information that he gave his step-son a spanking for misbehaving shortly before the crime took place. Later on he gives his knife to the filmmakers who turn it over to the prosecutors, who find his blood and his step-son’s blood on it. There is no follow up to the fact that he stated there was no reason for the blood on the knife, since he never used it before. But under questioning from the defense attorney, he now remembers cutting himself with it. This is a knife that could have very likely been used in the crime.

There is also a manager of a local fast-food place, who said on the late afternoon of the gruesome murders he called the police to his Bojangles because there was a black man in the woman’s rest room with blood all over him. The police, even though they were aware a bloody murder had just happened, did not apprehend this man or follow this lead up in their investigation.

The trial of Damian and Jason is hinged on the claim that they committed the act as a ritual killing for their satanic group, something that the state has absolutely no evidence on but the testimony of a mail-order doctor who claims to be an expert on cult groups. The accused both deny being in any kind of group, and no one can offer proof that they are in such a group. They call themselves loners. Damian has a girlfriend he fathered a baby with, and is not an active participant in any gang or cult. On camera his girlfriend states that Damian couldn’t harm anyone, she is confident that he couldn’t have done the crime. Jason could hardly say a word and seems to be mortified, not really aware of what is going on, and appears to have no connection with anything occult, except he likes to hang around with Damien and listen to heavy metal music.

Needless to say they are convicted of the crimes even though Jessie recants his confession and refuses to cut a deal with the prosecutor for a reduced sentence to testify against his friends because he would be lying, and his mother said that she would be in court to watch him to make sure he doesn’t tell a lie.

Damian gets the death penalty, while Jason gets a life sentence. Their sentences are now under appeal.

If ever there was to be a public outcry against how the judicial system works and the arbitrary use of the death penalty, this case of failed justice should be it. The film should give you food for thought about how unfair the judicial system can be for those who are poor. It was frightening for me to watch how the process works and that there is no outcry from the community about the injustice; and, even if this case is the exception to the way the courts operate, that most cases are handled with more of a search for justice and with less of a rush to judgment, which I sincerely doubt, this compelling documentary leaves me perplexed not only in my questioning of the verdict but in the whole process itself. I just wonder if our system is so flawed overall, that there is the very real possibility that an innocent person (or in this case three innocent people) — without the resources to mount a proper defense — can be sentenced to death because our system is so fallible!

REVIEWED ON 4/21/99 GRADE: B