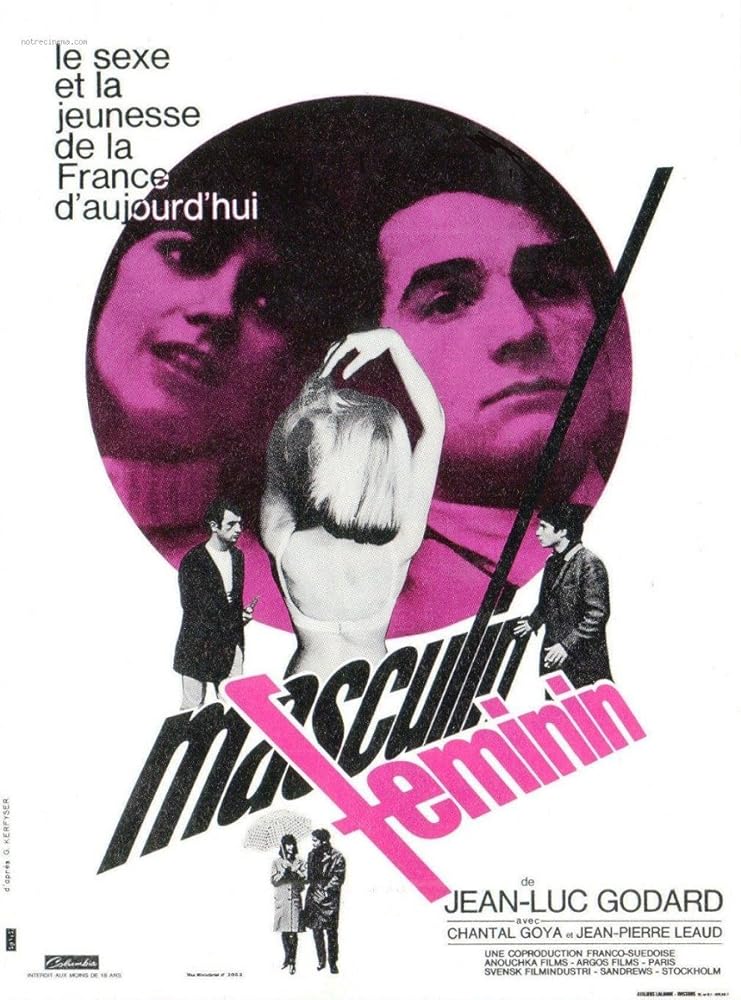

MASCULINE FEMININE (Masculin, Féminin)

(director/writer: Jean-Luc Godard; screenwriter: based on two Guy de Maupassant short stories The Signal and Paul’s Mistress; cinematographer: Willy Kurant; editor: Agnès Guillemot; music: Francis Lai; cast: Jean-Pierre Léaud (Paul), Chantal Goya (Madeleine Zimmer), Marlene Jobert (Elisabeth), Michel Debord (Robert), Catherine-Isabel Duport (Catherine-Isabelle), Eva-Britt Strandberg (Elle), Birger Malmsten (Lui), Elsa Leroy (Mlle 19 ans de ‘Mademoiselle Age Tendre’), Brigitte Bardot (Herself); Runtime: 105; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Anatole Dauman; The Criterion Collection; 1966-France/Sweden-in French with English subtitles)

“Foray into the mindset of the Children of the Sixties.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Jean-Luc Godard’s 11th feature, during his peak years of the 1960s, was a foray into the mindset of the Children of the Sixties, whom he called “The children of Marx and Coca-Cola.” Its narrative is about a serious-minded, impressionable, romantic, Communist revolutionary, 21-year-old named Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud), just returning from his dreaded military obligation and getting his act together as a protester of the Vietnam War and as an activist in Parisian labor disputes. In a café he becomes smitten with Madeleine Zimmer (Chantal Goya, real-life yé-yé star), a pretty girl his same age who aspires to be a yé-yé pop singer. Madeleine stylishly dresses young wearing flat heels or go-go boots and plays hard to get but the two soon become lovers; he moves into her flat with her two roommates Elisabeth (Marlene Jobert) and Catherine (Catherine-Isabel Duport). Their rocky relationship continues even though aside from a sexual attraction they don’t have much else in common. Madeleine cuts a bubblegum record that goes to No. 6 in Japan and later will have an unwanted pregnancy. Paul will either be pushed or willingly jumps out of a building window, leaving an unprepared Madeleine alone to deal with her pregnancy.

On top of that accessible story, Godard uses an episodic presentation to randomly fire away at many different things he observes about the Parisian youth of 1965 from their opinion of Bob Dylan as the one to lead them into the “promised land” of politics to a mocking of their overall lack of culture. It resembles a sociological account of the time’s climate and the thinking of its youth, done with the realization that there’s no such thing as an average French youth. In the background the election for France’s leader is a bitterly fought one between the victor de Gaulle over Mitterand. Godard calls this film technique his “15 Precise Facts.” Though lacking a strong central political point, Godard is in top form taking pot shots at all comers and especially at his favorite dislikes: pop culture, American arrogance, fashions, whitey not understanding the soul music of the blacks and political events covered in such a slipshod way by the media (such as the Vietnam War). In an episode called “The center of the universe,” Godard seems to be putting down both Paul, who naively calls his “center” love and Madeleine who vainly says her “center” is “me” (a member of the me-only generation). In another episode there’s a long interview with Paul, who has switched jobs from the magazine and is now doing interviews for an opinion poll service, of someone who won the title in a glamor teen magazine as Miss 19 (Elsa Leroy, real-life “Miss 19”). Godard mocks such trivial questioning as of little value to the world as the questions range from birth control to socialism and are a bitter depiction of the young lady, showing her woefully ignorant and unconcerned with world events. In the scene titled Mis-projection, played mostly for humor and to take a swipe at the international angels who might not have been ready for Godard’s “new wave” revolutionary free-style way of filming, Paul and his three female roommates attend a Swedish film where he complains that there’s subtitles, too much eroticism and finally complains to the projectionist about the misuse of the aspect ratio.

The loner, possible misanthrope, pseudo-intellectual and anxiety ridden Paul, whose only male friend is shown as a leftist union activist named Robert (Michel Debord), is nevertheless the charming self-indulgent radical who becomes the voice of his generation even though he’s not typical, is far too nervous and sad to be a spokesman for any group, is more a skeptic than a political realist and is unstable. It might as well be a description of Godard. The then 35-year-old filmmaker was changing lovers, going from Anna Karina to the more politically aware Polish woman Anne Wiazemsky. This film marked his more serious transition when he was still not fully certain of his views but certain he differed from both the new and older generation. His pessimism is justified by the troubled days after 1965, as the filmmaker looks over his shoulder and sees a world at war and at home a battle of the sexes. He dourly makes the female look like the intellectually inferior gender (the boys pull political pranks such as painting anti-war slogans on American cars and talk politics while the girls shop, dress well and do not concern themselves with the world). Goya is the ‘Pepsi Generation, while Léaud is the child of Marx. It’s the kind of film where graffiti is taken for the soulful meaning of politics and sex, and reality is played as a lark when Brigitte Bardot, playing herself, is reading from a movie script in the local café with Goya and Léaud at a nearby table.

Masculine Feminine” is based on two Guy de Maupassant short stories that are loosely adapted for Godard to bring in contemporary politics.

REVIEWED ON 1/28/2006 GRADE: A