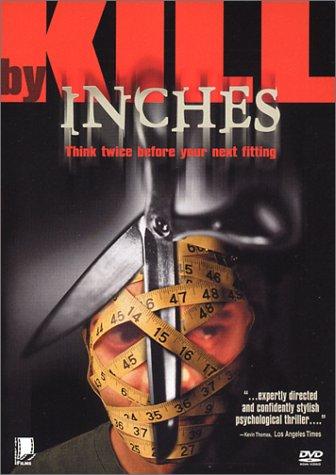

KILL BY INCHES

(director/writer: Diane Doniol-Valcroze/Arther Flam; cinematographer: Richard Rutkowski; editors: Elizabeth Gazzara/Ethan Spigland; music: Geir Jenssen; cast: Emmanuel Salinger (Thomas Klamm), Myriam Cyr (Vera Klamm), Marcus Powell (The Father), Christopher Zach (The Repairman), Stephanie Schmiderer (Albert’s Mother), Nicholas Tafaro (Albert); Runtime: 80; IFC/CineBlast; 1999)

“A derivative film that is as weird as a Quay Brothers one, but as stale as a month old roast.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A derivative film that is as weird as a Quay Brothers one, but as stale as a month old roast. NYU film graduates Diane Doniol-Valcroze (daughter of Cahiers du Cinéma cofounder) and Arther Flam make their debut with “Kill by Inches.” The subject is tailoring, sibling rivalry, madness, fantasies, and sexual frustration.

The talented French actor Emmanuel Salinger plays a young tailor, Thomas Klamm, who is in a sibling rivalry with his twin sister Vera (Myriam Cyr, a Canadian actress), also a tailor, as he aims unsuccessfully to please his authoritarian father (Marcus Powell). He is plagued by memories of childhood when after a spat with his sister, his father forced him to eat his entire tape measure as punishment — to the glee of Vera.

The dialogue is sparse and the method of filming is formally stylized. For most of this bleak noirish story the taciturn Thomas solemnly measures mostly unattractive patrons, which are the film’s most interesting scenes. But he’s an incompetent tailor, as his measurements are off. It makes him jealous that Vera is not only his father’s favorite, but she can accurately do measurements with only her naked eye.

Thomas is obsessed with getting the measurements right and pleasing not only his critical father but his customers. The camera pans to largely Freudian shots of his dark metropolitan workplace, a deserted area near the Manhattan Bridge, where the tailor’s objects of a large scissor, a suspended huge needle, and safety pins are symbolically infused into the young tailor’s sexual anxiety fantasies. The film’s arthouse appeal is to a postmodern philosophy, and it covers the same abstract territory as do Peter Greenaway’s films.

The tension boils over when Thomas screws up an alteration of a little boy’s pirate costume. His emotional problems over his work failures result in two murders (whether they really happened or were in his fantasies is not exactly clear). But it results in a renewed freedom to improve in his chosen craft. At the annual Tailor’s Ball Convention Gala, in which his main rival Vera is not present, he wins a contest in which tailors try to guess by eye the measurements of fully dressed models who go dancing by.

The film was too loaded down with basic Freudian symbolism to fully work as drama, but it sustained a tension as a curiosity piece even though its theme has been covered too often as of late to have much freshness other than setting a creepy mood.

REVIEWED ON 3/21/2002 GRADE: B –