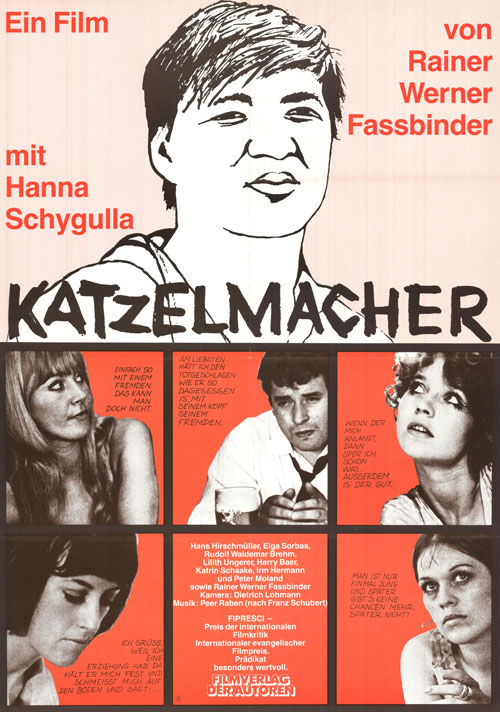

KATZELMACHER

(director/writer/editor/producer: Rainer Werner Fassbinder; cinematographer: Dietrich Lohmann; music: Peer Raben; cast: Hanna Schygulla (Marie), Hans Hirschmüller (Erich), Lilith Ungerer (Helga), Rudolf Waldemar Brem (Paul), Elga Sorbas (Rosy), Harry Baer (Franz), Irm Hermann (Elisabeth), Peter Moland (Peter), Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Jorgos), Doris Mattes (Gunda), Hannes Gromball (Klaus); Runtime: 88; MPAA Rating: R; Wellspring Films; 1969-W.Ger.)

“There’s a blinding nasty truth about the young filmmaker’s own generation that he richly exploits…”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Fassbinder’s black-and-white filmed Katzelmacher (the title translates from the Bavarian slang for “stud”) is based on his own anti-theater play, which won some public acclaim. It’s set among a bunch of men and women who are twenty-somethings living in a Munich suburb, and who aimlessly hang out together in the street in front of their apartment complex or in the neighborhood tavern. They are idlers filled with fear and hatred and illusions about the life they can’t stomach around them, who do nothing but bitch, gossip, mock each other and their neighbors, booze it up, smoke cigarettes, and sleep with each other. Katzelmacher becomes a stinging commentary about youthful alienation and prejudice against foreigners and the travails of youthful romance, which is played against the backdrop of the Germany postwar economic boom. There’s a blinding nasty truth about the young filmmaker’s own generation that he richly exploits, showing their ugly side and their vulnerabilities as they try to dig their way out of the boredom that fills their lives but who are without the proper tools to dig their way out of their rut.

It should be noted that Fassbinder had to rely on state funding to make his films, and he can certainly be challenged for biting the hand that feeds him. The filmmaker’s attitude is that he’s an outsider and that even though outsiders are needed to bring new life to the stagnant German culture, they are never welcome. In order for Fassbinder to achieve success in this milieu, he aped the Hollywood director by organizing his own production base and made it function like the American studio system. As in most of his early films, Fassbinder fills the screen with despair and his subject matter themes always seem to be about the exploitation of feelings. Here, he does this in a highly stylized and artistic manner by examining the dynamics among couples from both “without” and “within” themselves. This film was the winner of the German Film Awards as outstanding feature film.

As in all Fassbinder films, there are slogans spoken by the characters or flashed across the screen. This film opens with the crawl: “It’s better to make new mistakes then to perpetuate old ones.” A bunch of aimless youths hang out in their neighborhood street and interact with each other in such a disarmingly comfortable way as only intimates can. The men act bored, macho and abusive toward the women; the women unhappily yearn for love and walk together arm in arm conveying a false sense of solidarity while talking harshly about the others and their own delusional aspirations. Paul (Brem) and Helga (Ungerer) have a volatile sexual relationship that they can’t abandon despite her miscarriage caused by him punching her in the stomach, as they remain engaged through all sorts of abuses. Also, Paul holds back the secret from her and the group that he gets money from a stranger to the group, Klaus (Gromball), by having sex with him. The sexy Rosy (Sorbas) thinks she’s better than the other girls and aspires to be an actress and services the men sexually for a charge, which makes the other girls sneer at her behind her back that she’s a slut. The only one who admits ponying up some coin to her is Franz (Harry Baer), the nicest group member and the only one who works and has money. He’s her main customer, and is mistakenly looking for love from her. But that’s not something she can give, as she’s selfishly doing everything only for her possible film career. Gunda (Mattes) is considered the ugly duckling of the group, something she doesn’t herself believe as she does not lack for self-confidence. Her boyfriend is working in another town and she fills her lonely time by snooping on the others. The highlighted couple is the surly Erich (Hirschmüller) and the cute and loving Marie (Hanna Schygulla), who is willing to degrade herself by accepting Erich’s abuse as long as he doesn’t leave her which would embarrass her in to the others. Elisabeth (Hermann) and Peter (Moland) make for another unhappy couple. She’s got the money and lords it over the apish and sullen Peter, whom she lets live rent free in her swell pad and feeds him and gives him money for booze and smokes. She says she can’t help being attracted to men who are starting to lose their hair. Even though she went to school with the others, she considers herself superior to them and does not stay with them.

Things pick up in intensity when Elisabeth rents out a small room in her place, in which she overcharges at 150 marks, to a Greek immigrant (played by Fassbinder), who can’t speak German but came here to earn more money as a worker than he can back home to support his wife and two children. His stay in Elisabeth’s brings about the ugly rumors that he’s having sex with her. He becomes the target of the group’s xenophobia and when he ends up going out with Marie they beat him up and make him think twice about staying in Germany.

It’s a plotless film that in its artistry hones in on the disaffected group it makes the film’s subject, and in Fassbinder’s minimalist and distinctive approach to filmmaking it overcomes its bleak mise-en-scénes with the power of its acerbic observations. Fassbinder yearns to know if anyone can tell him what is ‘normal’ and if there can be love without pain. Everything becomes open to discussion, as the filmmaker has no desire to push any agenda down the viewer’s throat.

REVIEWED ON 11/23/2002 GRADE: B