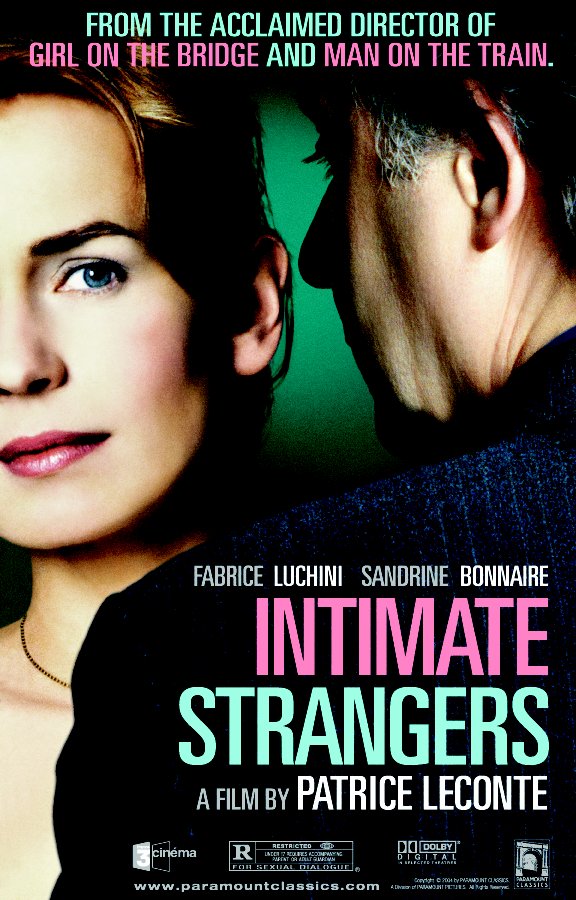

INTIMATE STRANGERS (Confidences Trop Intimes)

(director/writer: Patrice Leconte; screenwriter: Jerome Tonnerre; cinematographer: Eduardo Serra; editor: Joëlle Hache; music: Pascale Estève; cast: Sandrine Bonnaire (Anna), Fabrice Luchini (William Faber), Michel Duchaussoy (Dr. Monnier), Anne Brochet (Jeanne Faber), Laurent Gamelon (Luc), Hélène Surgère (Mrs. Mulon), Gilbert Melki (Marc), Urbain Cancelier (Chatel, elevator phobia patient), Isabelle Petit-Jacques (Dr. Monnier’s Secretary); Runtime: 103; MPAA Rating: R; producer: Alain Sarde; Paramount Classics; 2004-France in French with English subtitles)

“More like a voyeuristic fantasy that overstayed its welcome than a real romance.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Veteran French director Patrice Leconte’s (“The Hairdresser’s Husband”/”Monsieur Hire”) Intimate Strangers is his 20th feature film. It’s a sardonic comedy/psychological thriller in the spirit of both Hitchcock’s ”Vertigo” and an outrageous TV soap opera. The screenplay is by Jérôme Tonnerre and co-written by Leconte. Its premise revolves around a case of mistaken identity and builds to an erotic cat-and-mouse game between a fake therapist and patient. This suspenseful relationship held my interest but never fully moved me, as the relationship turned from titillatingly amusing to too much like a lightweight screwball comedy to have much of an impact.

Anna (Sandrine Bonnaire) mistakenly walks into the wrong office in her first appointment with psychoanalyst Dr. Monnier (Michel Duchaussoy) and ends up revealing personal things about her married life to tax lawyer William Faber (Fabrice Luchini), such as not having sex for the last six months with her unemployed domineering husband Marc (Gilbert Melki). When she learns of her mistake, she returns anyway to see the stuffy, lonely, repressed middle-aged Faber and continues with her weekly therapy sessions, impressed that he is such a good listener. His only reactions to things that startle him, is to raise his eyelids in a gesture of surprise. Faber has followed the same profession as his deceased father and has inherited his father’s nosy secretary (Isabelle Petit-Jacques) and lucrative business, which comes with an apartment plus an outer office. He has lived here all his life, though as a youth he dreamed he would become an explorer as an escape from such a claustrophobic fate.

Faber becomes obsessed with Anna, but doesn’t know how to make the first move and tell her he has fallen in love. The attractive woman realizes that but looks upon him as only her therapist, as she is too neurotically absorbed with her troubled marriage to a jealous man with issues. Confused by what is happening to him, Faber goes down the hall to consult with Dr. Monnier. He tells him that a tax attorney isn’t that much different than a psychiatrist — both deal with “what to declare and what to hide.” Faber also consults with his would-be novelist teacher ex-girlfriend Jeanne, who has left him for a jock (Laurent Gamelon) who runs a fitness center. Jeanne is still best friends with him and advises him “to hump or dump her.”

At its best, the film shows Faber loosening up and becoming less repressed when he realizes how much he loves Anna (in his apartment he animatedly dances to Wilson Pickett’s ”In the Midnight Hour”). Anna’s transformation comes about by getting things off her chest with him that she never told anyone else. She suddenly emerges free to explore new options in her life and do things she always wanted to do but couldn’t, and can now confront her imposing hubby. They both benefit from these fake therapy sessions, and the mystery remains if these opposites are suited for each other. The film pokes fun at the psychiatry profession, as the fake therapist proves better suited for the job than the greedy, pompous and nonsensical dogmatic spieling real therapist.

The film is artfully directed by Patrice Leconte, magnificently acted in an understated manner by the almost always wide-eyed Fabrice Luchini and the engagingly sexy Sandrine Bonnaire, and the story is not without certain charms and a worthwhile message about the importance of communicating with others. But it falls too easily into a French bourgeois farcical romantic comedy/melodrama to suit my taste, and left me feeling it was all too safe in its storytelling and payoff– seeming more like a voyeuristic fantasy that overstayed its welcome than a real romance. It was hard to see what romantic interest Anna would have with such a plain looking and uptight man, despite liking him as a person. But that is what we are asked to believe is possible–that opposites do attract. All the teasing romantic possibilities put forward don’t amount to much more than a soap opera tale that has hints of more unrealized psychological depths that unfortunately never materialized.

REVIEWED ON 9/8/2004 GRADE: B-