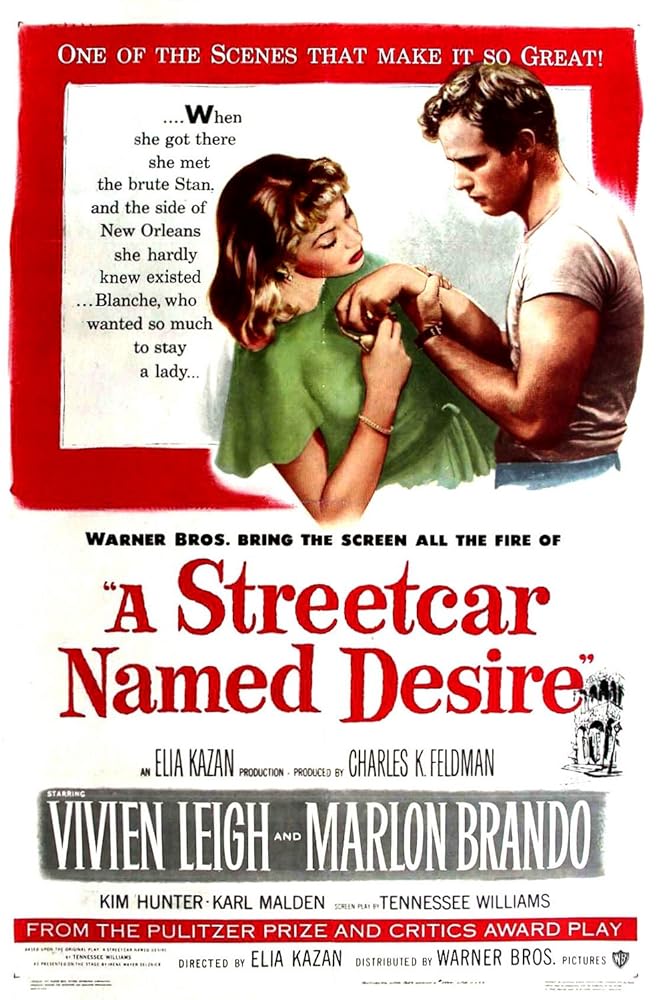

A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE

(director: Elia Kazan; screenwriters: Oscar Saul/from the play by Tennessee Williams; cinematographer: Harry Stradling; editor: David Weisbart; music: Alex North; cast: Vivien Leigh (Blanche DuBois), Marlon Brando (Stanley Kowalski), Kim Hunter (Stella Kowalski), Karl Malden (Harold “Mitch” Mitchell), Peg Hillias (Eunice Hubbell), Rudy Bond (Steve Hubbell), Nick Dennis (Pablo Gonzales); Runtime: 122; MPAA Rating: PG; producer: Charles K. Feldman; Warner Brothers; 1951)

“Lacks the poignancy you could almost swear was a given, considering it was adapted from an acclaimed Tennesse Williams play.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Suffers the ill-fate of most plays transferred to film, even classics like this one, as it is too talky for a film. Tennessee Williams’ 1947 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, filmed in black-and-white, is directed in an intense overblown theatrical manner by Elia Kazan–who also directed it on Broadway. He uses many close-ups of the characters, but the grimy realism sought seemed forced. The screenplay is by Oscar Saul, the original music is scored by Alex North. The film features Marlon Brando (who played the same part on the stage) exhibiting his abilities as a Method actor, which left critics to both admire and poke fun at his twitching acting style. He chews gum, scratches, mumbles and stammers, and calls out in primal agony to Stella (Hey, Stell – Laaahhhhh!) in this dramatic shocker of rape and futility in New Orleans. Once known for its steamy sex, it seems like tame material when viewed these days with even the rape scene more symbolic than explicit. The lively brilliant performances were more interesting than the stylized psychological drama acted out on the unnatural studio sets. Vivien Leigh (the English-born actress took the part Jessica Tandy played on the stage) and Brando battle it out for who ultimately steals the spotlight. Leigh’s grandiloquent performance contrasted with Brando’s bombastic one, and the winner was clearly Brando according to my count of who hit harder. Leigh’s showy tics as a refined Southern belle trying against all odds to still be a lady were no match for Brando’s bigger than life portrayal of a vulgar working-class brute. Kim Hunter (also in the play) gave a marvelously understated performance as a good-hearted soul who made everything a little less hysterical to balance the uber performances from the leads.

“Streetcar” was nominated for 12 Oscars and won four Oscars in 1951 including Best Black and White Art Direction (George James Hopkins & Richard Day), Best Actress (Vivien Leigh), Best Supporting Actress (Kim Hunter), and Best Supporting Actor (Karl Malden). Bogie in “The African Queen” beat out Brando for the Best Actor award.

Set in the French Quarters of New Orleans just after WW11, penniless, deteriorating and unstable Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) arrives in New Orleans to visit her more stable married pregnant younger sister Stella Kowalski (Kim Hunter). She lives in a cramped one-bedroom apartment on the ground floor in the slum part of the Quarters with her unrefined army war veteran hero and factory worker hubby Stanley Kowalski (Marlon Brando), someone she loves very much in an overt physical way. The low-born Stanley is referred to derogatorily by Blanche as a Pollack, but Stella has learned a long time ago to accept him as he is–a dirty T-shirt wearing and beer guzzling slob. Stanley takes an immediate dislike to the vulnerable genteel Blanche and begins a relentless campaign of crudely badgering her. Stella acts protective of her sis, as Stanley at first thinks the old maid English teacher Blanche is holding back money she got from losing to creditors the Mississippi family country home–Belle Reve–and insists on seeing the papers.

Mitch (Karl Malden, he was also in the play) is one of the more polite card-playing cronies of Stanley’s, who becomes involved with Blanche. The lonely Blanche encourages the lonely mama’s boy Mitch as a suitor and sees him as a way out of her predicament–a way to regain her dignity and leave the cramped apartment. But Blanche deceives him and plays the part of an old-fashioned woman to her admiring suitor by keeping him at bay–telling him that she is waiting for marriage before sex. Blanche also pretends to be much younger, and never allows Mitch to see how old she looks in the sunlight. This relationship goes on for five months, but ends badly as Stanley spills the beans when he learns from his acquaintances that Blanche was a prostitute in her hometown and lost her teaching job due to her relationship with a 17-year-old male student.

After Stanley rapes her, Blanche is also exposed as a liar, being delusional, and who pitifully never recovered when a long time ago her young husband committed suicide (in the play it’s because of a homosexual encounter, while the film keeps it vague). Just before the woman suffering from a nervous and mental breakdown is taken to a rest home, she states “I always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

The film though faithful to the play, still never captures its subtlety or dark humor. Aside from the great performances over the battle of the sexes it nevertheless lacks the poignancy you could almost swear was a given, considering it was adapted from an acclaimed Tennessee Williams play.

REVIEWED ON 7/16/2004 GRADE: B