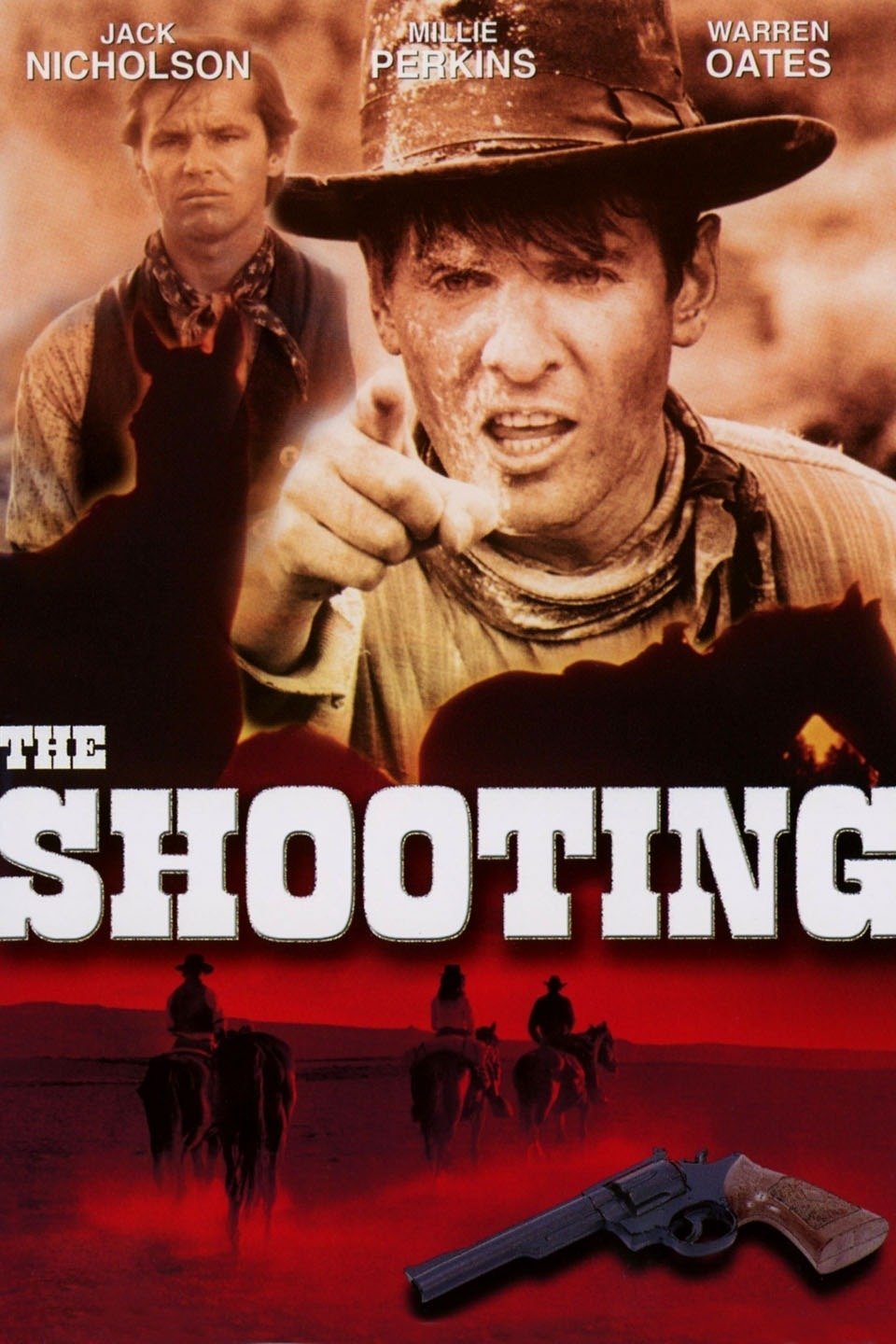

SHOOTING, THE

(director: Monte Hellman; screenwriters: Adrien Joyce (a.k.a. Carole Eastman); cinematographer: Gregory Sandor; editor: Monte Hellman; music: Richard Markowitz; cast: Will Hutchins (Coley Boyard), Millie Perkins (Woman), Jack Nicholson (Billy Spear), Warren Oates (Will Gashade), Charles Eastman (Bearded man); Runtime: 82; MPAA Rating: G; producers: Monte Hellman/Jack Nicholson; Liberty Home Video; 1967)

“If there ever was an existential Western, this one is it.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

If there ever was an existential Western, this one is it. It was written by Adrien Joyce and produced by two of Roger Corman’s protégés, Jack Nicholson, in a starring role, and Monte Hellman, in the role of director. Roger Corman financed the film with $150,000, as the psychologically diverting film was shot in seven weeks in Utah back to back with the equally mysterious Ride in the Whirlwind. The minimalist storyline followed along the lines of the “hunter as hunted”, as it sets a chillingly bleak mood of fear and despair.

It follows ex-bounty hunter Will Gashade (Warren Oates) and his good-natured but dumb young sidekick Coley (Will Hutchins), around for comic relief, taken aback by their friend Leland Drum being killed for no good reason and Will’s twin brother on the run because he might have killed a little one, maybe a child, in town. They are soon approached by an impertinent unnamed woman (Millie Perkins) who offers big money to persuade them to guide her into the desert on a mission she refuses to reveal. Following them is Billy Spear (Jack Nicholson), a sadistic killer, who soon joins them and spreads his hateful vibes to all but the lady. His relation to the woman is not totally clear, except he’s been hired as a gunman and that the determined lady is after some unnamed prey.

Warning: spoiler in the next paragraph.

The viewer knows as little as Will does about what’s going down. At one point Will explains why he goes on this mysterious journey “It’s just a feeling I’ve got to see through.” He soon figures out that they’re after his brother and tags along hoping to prevent the killing. At the moment Will learns his suspicions were correct his brother, from a distance, mistakenly guns him down.

The film had such weird moments as Coley offering candy to a bearded man left wounded and dying of thirst in the desert. But as strange as the film was, it kept all the familiar notions of the Western intact and it never lost its power as a Western. Its storyline had the kind of fatalism that Albert Camus could appreciate and one that few Westerns ever touch upon with such urgency, which made it a cult favorite when released after Jack Nicholson achieved stardom in the early 1970s.

REVIEWED ON 12/28/2005 GRADE: A