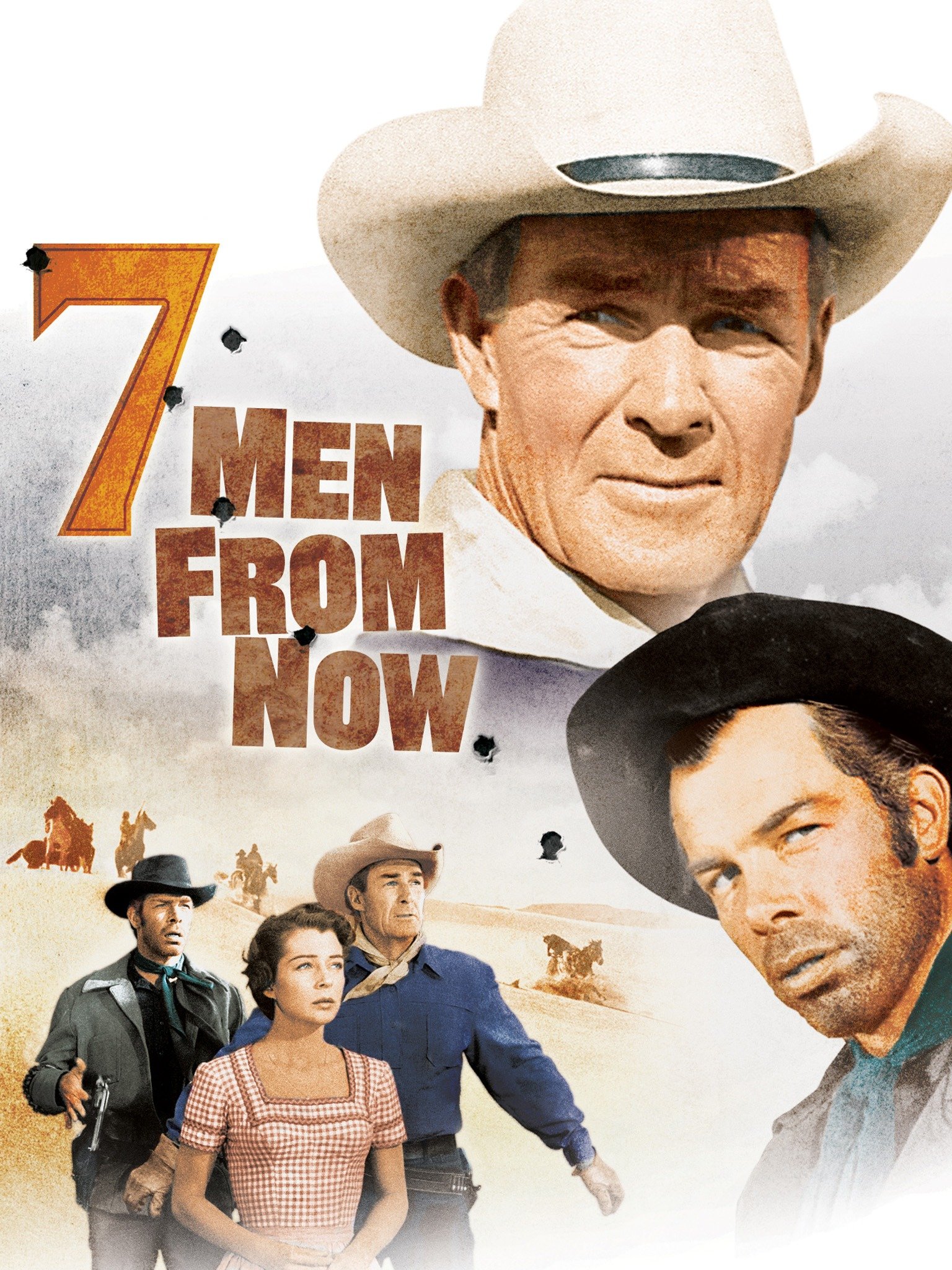

SEVEN MEN FROM NOW

(director: Budd Boetticher; screenwriter: from the story by Burt Kennedy/Burt Kennedy; cinematographer: William H. Clothier; editor: Everett Sutherland; music: Henry Vars; cast: John Barradino (Clint), Donald Barry (Clete), Fred Graham (Hanchman), Annie Greer (Gail Russell), John Larch (Pate Bodeen), Lee Marvin (Bill Masters), Steve Mitchell (Fowler), John Phillips (Jed), Walter Reed (John Greer), Chuck Roberson (Mason), Randolph Scott (Ben Stride); Runtime: 78; MPAA Rating: NR; producers: Andrew V. McLaglen/Robert E. Morrison; Warner Brothers; 1956)

“A terrific Western especially for those who take their oaters seriously.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A terrific Western especially for those who take their oaters seriously. It unites for the first time Budd Boetticher with Randolph Scott (they made six other Westerns together) and screenwriter Burt Kennedy. John Wayne’s Batjac produced the film (they previously produced Boetticher’s The Bullfighter and The Lady) and when the Duke was unavailable to star he suggested Scott. The little known film is up there with The Tall T, Comanche Station and Ride Lonesome in Boetticher’s opus of great Westerns (they are also films the trio worked on together). “Seven” is a chilling revenge story that falls back on Boetticher’s recurring theme of a decent guy fighting obsessively for what he believes is right even though it doesn’t seem to make much sense and in the end learning to have less pride (could easily be substituted as the filmmaker’s own struggle in dealing with Hollywood).

It begins on the night of a rainstorm on the Arizona desert trail and a horseless Ben Stride (Randolph Scott)–starving Indians took his horse for food some 10 miles back–arrives at the campsite of two outlaws and outdraws them after being served coffee. He then helps easterners, Annie and John Greer (Gail Russell and Walter Reed), get their wagon out of a mudhole, as they head for California. At a relay station the trio meet Bill Masters (Lee Marvin) and Clete (Donald Barry), who clue us in that Stride was the former Silver Springs sheriff (lost an election 6 months ago) whose wife was killed when the express office she worked at was robbed by seven bandits of its Wells Fargo box that carried $20,000 worth of gold and that Stride is hunting down the five remaining men. Masters and Clete didn’t participate in the robbery, but want to steal the gold from the robbers. They figure Stride will lead them to the outlaws, so they tag along. In a classic scene, Master’s who had been arrested twice by Stride, recognizes that there’s a chemistry between the pretty Annie and Stride and tells a tall story that needles Stride for repressing his feelings for her and mocks her tin-horn hubby for being “half a man.” From that psychological clash we realize that it’s inevitable that the two gunfighters will have a showdown before the third act concludes.

A twist comes when it’s learned that John Greer, without telling his wife, is carrying the Wells Fargo box to meet Pate Bodeen (John Larch) in Flora Vista. The outlaw promised to pay John $500, as the gullible man didn’t realize the severity of the crime and what he was getting himself into. When Stride learns of this he sets a trap for the outlaws, and after all the outlaws are gunned down the only two left standing are Masters and Stride. In a memorable scene the two go for their guns, but we do not see Stride draw as we only see Master’s falling down shot. That scene conveys that Stride is too fast for the camera to catch.

Scott gets into his character’s skin and has a commanding presence as the regal no-nonsense determined guy who is deeply haunted by his loss, but never loses his classy ways even though overwhelmed by his loss. Marvin makes for an engaging villain, who makes his sinister and untrustworthy character as likable as possible. Boetticher’s directing ability is first-class, as good as the great John Ford and Howard Hawks. For a Western, the economical script is impressively intelligent, witty and psychologically involving (more so than your average oater). If Boetticher didn’t self-destruct while making his bullfighter pic Arruza in Mexico, he would have most likely been better known and more recognized today as one of Hollywood’s finest–something he deserves, anyway, despite his career curtailed by the studios who considered him a madman. The film was beautifully shot by William H. Clothier in Long Pine, California, a seemingly natural location to make Westerns and used often by Boetticher and other Western directors such as Raoul Walsh.

REVIEWED ON 12/23/2005 GRADE: A