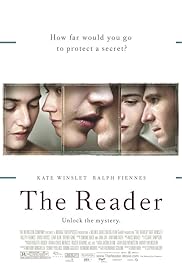

READER

(director: Stephen Daldry; screenwriters: David Hare/based on the book by Bernhard Schlink/translated by Carol Brown Janeway; cinematographer: Chris Menges/Roger Deakins; editor: Claire Simpson; music: Nico Muhly; cast: Kate Winslet (Hanna Schmitz), Ralph Fiennes (Michael Berg), David Kross (Young Michael Berg), Lena Olin (Rose Mather/Ilana Mather), Bruno Ganz (Professor Rohl), Matthias Habich (Peter Berg), Vijessna Ferkic (Sophie), Hannah Herzsprung (Julia); Runtime: 123; MPAA Rating: R; producers: Anthony Minghella/Sydney Pollack/Donna Gigliotti/ Redmond Morris; Weinstein Company; 2008-USA/Germany)

“Succeeds on its own terms mainly because of Kate Winslet’s earnest Oscar fixated performance.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Reader is based on German author Bernhard Schlink’s 1995 bestselling partly autobiographical novel and is written by playwright David Hare in a pensive subdued style that quietly reflects on the collective guilt of the Germans who remained silent over the Holocaust in the post-WW II period. It tells nothing we haven’t already heard about Nazis and death squads from pics like Apt Pupil and Music Box, but succeeds on its own terms mainly because of Kate Winslet’s earnest Oscar fixated performance and its top line production values. It’s frightening to realize that there have been over 250 films made to date about the Holocaust; this one gets lost in the shuffle except for the different slant it takes, as it makes an impoverished illiterate Nazi death-camp guard to be the sympathetic protagonist more than the rich writer survivor Jewish victims.

Stephen Daldry (“Eight”/”The Hours”/”Billy Elliot”) directs the morose and mostly lifeless drama with great craftsmanship, while photographers Chris Menges and Roger Deakins paint a stylish looking maroon colored post-Holocaust look on a Germany that still hasn’t settled matters for its second and third generation citizens on its foul deeds of the past by its first generation.

This provocative film muddies the waters as it throws out a number of unanswerable philosophical questions that reflect on moral responsibility, justice, legality, the banality of evil and redemption. It also brought into the fray questions of education and literacy, and how much they influence a person’s judgment to do what’s right (it assumes that we now know it’s better to read on our own a classic like The Cherry Orchard by Chekhov than Hitler’s bestseller of Mein Kampf).

It opens in Berlin in 1995, where dour successful middle-aged lawyer Michael Berg (Ralph Fiennes), the film’s narrator, bids a chilly goodbye after serving breakfast to his one-night stand and rushes off to court. Later when alone in his sleek contemporary apartment, Michael stares out a window at a passing train and is suddenly transported back to 1958 in Neustadt when he was a 15-year-old (David Kross) who took sick on a trolley and puked in a strange courtyard only to be looked after by the 36-year-old taciturn trolleycar fare collector Hannah Schmitz (Kate Winslet) returning home after work.

At home with his middle-class family, Michael is treated for three months with scarlet fever and in the summer returns to Hanna’s dank apartment. She gruffly calls him “kid” and deflowers the appreciative horny Michael, and as a ritual has him read aloud to her books from his literature class such as Homer’s “The Odyssey,” Tolstoy’s “War and Peace,” Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.” The discreet affair, which he never told anyone about, continues all summer until one day he finds his mysterious lover has vanished.

In 1966 Michael’s in law school in Heidelberg taking a seminar class with a sensitive law professor (Bruno Ganz), who is a stickler for legality over morality. Michael attends with his class the Nazi war trial of six women Auschwitz SS guards accused of keeping 600 Jews under their charge locked in a church during a fire where most died and with other crimes against humanity. Michael is stunned to learn of Hanna’s past, but can’t get himself to communicate with her during the trial even after realizing she’s about to get a stiff sentence because she’s more ashamed of being illiterate than of being the guard most responsible for carrying out those war crimes and he knows that her guarded secret if revealed would lessen her sentence.

The tight-lipped Michael soon marries a fellow law student and has a daughter named Julia, but the marriage breaks up and his loving daughter lives apart from him. During Hanna’s twenty years in prison Michael never visits but sends cassettes of him reading from the classics, which teaches her how to read. When Michael sees an aged Hanna after twenty years, he sees a tragic figure who symbolically has paid her debt to society supposedly for all the other Germans like her who so willingly served the Nazi war machine out of ignorance and who have been outed so that now they are forced to face their past.

The film’s moral center about facing the truths behind the country’s shameful past comes about in the centerpiece climactic scene when Michael visits in Manhattan a wealthy Holocaust survivor of Auschwitz (Lena Olin, in a dual role as both mother and daughter), who wrote a book with her now deceased mother about the camp and both women pointed an accusing finger at Hanna during her trial. The collected, articulate, and stylish woman lectures the depressed Michael, who suffers from a bad case of guilt by association and has remained silent all these years about his contact with the former Nazi guard, that the Holocaust cannot be forgotten or trivialized. This was the only scene in the film where the Holocaust lecture, mostly aimed at second generation victim survivors and those second generation Germans too afraid to admit contact with any Nazi because it might strain their current position in society, at least had a charge to it. It leaves the lingering question if those we loved can ever be forgiven for their past evil deeds or if those of other generations can ever come to terms with an older generation that so easily accepted evil.

This is the kind of beautifully made film that begs us to look at a death-camp guard in a new light of sympathy. It forces us into a corner to accept Hanna being humanized, and that her barbaric job was taken because that was the only one an illiterate German like herself could get and that under different circumstances Hanna would have never taken such a job but would have been a good citizen and hard worker (as proven by her latest trolley job). That certainly may be true, but I must ask since when is being illiterate an excuse to act in such an inhumane way and why should someone as unremorseful and not able to be soul searching be treated sympathetically even if she’s now a better person because she can read! The film lost me when it just seemingly wanted me to ignore that this ignorant woman even though only a lowly cog in the Nazi war machine, nevertheless was in part responsible for the deaths of 300 Jewish camp inmates.

This is a reflective film that ironically never penetrates Hanna’s thoughts or her inner character, and since she refuses to be introspective we never know what she’s thinking but only her outward demeanor. This keeps things tasteful and intelligent, but also eerily distant. What we are asked to read into Hanna’s story is that it relates to the fate of the modern German and that a better educated Germany will lessen the chances of history repeating, which will get no argument from me. The only problem is that I don’t think this film was strong enough in its convictions to present that case dramatically, as good taste alone cannot make up for a film that lacks fire in its belly. I also don’t think that it has much to say that is reassuring about Germany’s still haunting collective guilt about WW II. Maybe the book, which I did not read, did so with a greater depth, but the movie was too superficial to make much of an impact except as a wonderful acting exercise for Winslet.

REVIEWED ON 2/21/2009 GRADE: B-