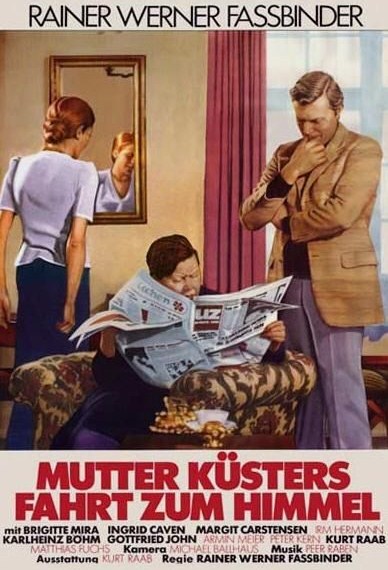

MOTHER KUSTERS GOES TO HEAVEN (Mutter Kusters Fahrt Zum Himmel)

(director/writer: Rainer Werner Fassbinder; screenwriter: from the story Mutter Krausens Fahrt Ins Glueck by Heinrich Zille; cinematographer: Michael Ballhaus; editor: Thea Eymèsz; music: Peer Raben; cast: Brigitte Mira (Emma Küsters), Ingrid Caven (Corinna Coren), Margit Carstensen (Frau Marianne Thälmann), Karlheinz Böhm (Karl Thälmann), Irm Hermann (Helene), Gottfried John (Niemeyer), Armin Meier (Ernst), Peter Kern (Nightclub manager), Matthias Fuchs (Knab); Runtime: 105; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Christian Hohoff; New Yorker Films; 1975-West Germany-in German with English subtitles)

“The provocative filmmaker manages to show worker exploitation on the left while still hitting hard at the right.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A wonderful Rainer Werner Fassbinder (“Ali: Fear Eats the Soul”) politically orientated black comedy, where the provocative filmmaker manages to show worker exploitation on the left while still hitting hard at the right. For this marvelous effort in truth telling, sparing no who is an exploiter, Fassbinder earned the unique distinction of having his film banned from both the official Berlin Festival and The Forum, its fringe festival. It’s not easy to get both the establishment and the avant-garde so angry at you, and I admire him all the more for that.

It opens in Frankfurt, Germany, asa dowdy plump older woman,Emma Kusters (Brigitte Mira), is busy in the kitchen doing piece work by assembling alarm clocks and packing them in cardboard boxes and defending why she has added canned sausages to the stew with her disagreeable, bitchy and domineering pregnant daughter-in-law Helene (Irm Hermann), as her passive factory worker son Ernst (Armin Meier) is helping with the piece work and looks on quietly trying not to offend either woman over their differing views on the health value of the meat. Over the radio it’s announced a chemical factory worker went berserk and killed the personnel manager, the boss’s son, and then took his own life. The news doesn’t register until later when a colleague of her husband’s comes by to tell Emma that it was her husband Hermann, of forty years, who did this irrational act and for no apparent reasons–though the plant was about to experience massive layoffs, but since he worked there for over twenty years without ever complaining it’s perplexing to think that’s the reason for his actions since the layoffs wouldn’t effect him immediately. Reporters flood her house for interviews and photos and there are screaming newspaper headlines of exclusive reports of “The Factory Murderer.” Mrs. K.’s self-absorbed, talentless cabaret singer daughter, who has taken the stage name Corinna Coren (Ingrid Caven), quits her dead-end Munich singing job and arrives in Frankfurt. Mom thinks it’s to comfort her in her time of need but instead she connects with pushy opportunistic magazine photographer/journalist Niemeyer (Gottfried John), who turned out to be a lout after promising Mrs. K. to write the truth about her hubby as a peaceful and quiet man whom she loved. But he twists things around to make it sound as if he were a rowdy, child-beater, wife-beater and ill-tempered drunk. He explains the reason he sensationalizes the story with the Nazi excuse that he was just doing his job. Corinna deserts mom to move in with Niemeyer, who uses his connections to get her a gig at a nightclub that advertises her, to draw in the crowd, as “The Daughter of the Factory Murderer.” The weak-minded Ernst is bullied into going along with his sullen, petty bourgeois aspiring wife on a Finland vacation to escape the scandal and when they return the couple move out on the insistence of the harridan wifey. At the factory, management tells her she can’t collect on her hubby’s pension and that the union agrees that their stance is legal. Left alone and wanting to set the record straight about what a good man her Hermann was, she’s befriended by a wealthy couple with connections, the Thälmann (Margit Carstensen & Karlheinz Böhm), who exploit her loneliness to recruit her into the German Communist Party. She joins not for political reasons but because they are the only ones who listen to her and keep her company, and pretend they care and will set the record straight about her hubby’s actions. But after she joins and gives a straightforward talk, no one helps her as promised. She is then sweet-talked by a radical anarchist, Knab (Matthias Fuchs), who promises action, and when time passes and there’s no one left to talk to (no worker from the factory visits and her family abandons her) she agrees to go with a few members of Knab’s group to demand a retraction from the magazine that Niemeyer works for. While there the group demands all political hostages be freed and take the reporter and his editor as hostages by gunpoint. The film has two different endings, depending which DVD you catch. In the one I had there’s a shootout with police and the dazed Mother Kusters is trapped in the middle of it, as she looks stunned and has lost track of what’s going down. It ends with a freeze-frame. A follow-up text explains that the police gunned Mrs. K. down. In the other version, Mrs. K. and two anarchists stage a sit-in at the magazine’s editorial offices. The editor and his staff ignore them and leave; then the pair of anarchists also split, leaving Mrs. K. alone until a night watchman, a widower, invites her to his place for a meal of apples and potatoes. In any case, in the end, she is betrayed by everyone, but her humanism, purity and honesty prevails making her a better person than any of those so-called superior folks.

The director was never more on target railing against all exploiters: political users from both the right and left, the mediocre, capitalists, unionists, cold-hearted family members, false friends and phony reporters, who are all living a lie and when confronted by a bewildered innocent take advantage of her vulnerability and exploit her for their own personal reasons leaving her looking bad in the eyes of the gullible public. It’s a powerfully spun tale about urban alienation, exploitation and the corruption of society. No one group comes out of this scathing attack without looking bad. The crazy thing is that Fassbinder’s seemingly perverted view lumping together the bourgeois, communists, health nuts, anarchists, radicals, capitalists and the media as one and the same bad apple is not wrong. It’s just like Mother Kusters says “Everybody is out for something. Once you realize that, everything is much simpler.” Fassbinder just takes them all on in this well-acted and accessible film.

REVIEWED ON 5/20/2006 GRADE: A https://dennisschwartzreviews.com/