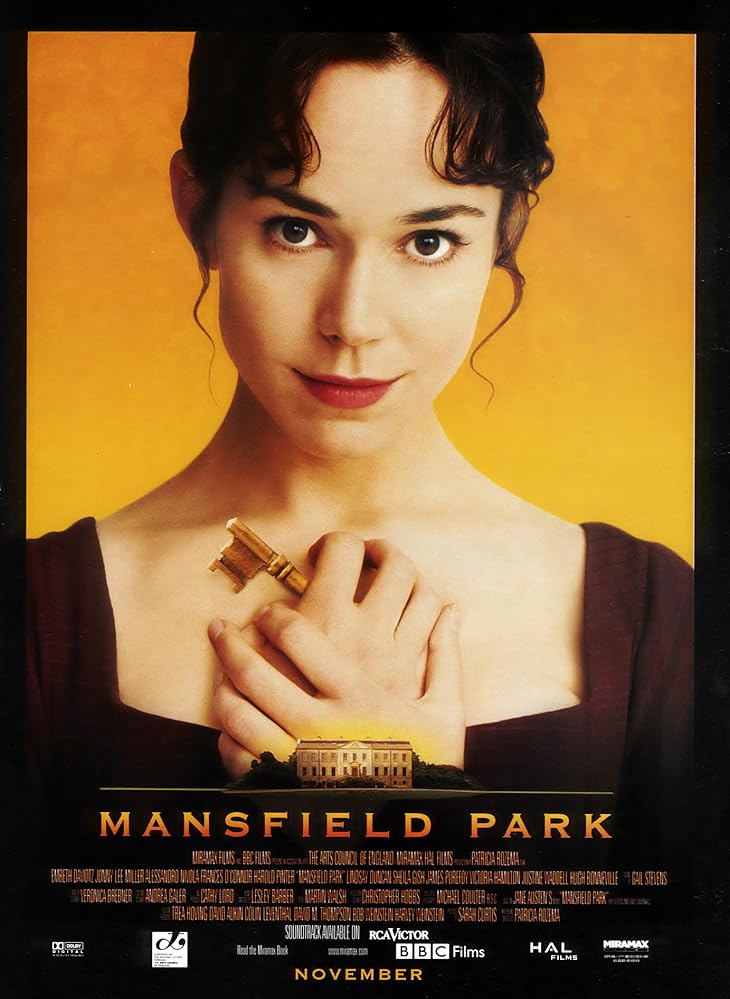

MANSFIELD PARK

(director/writer: Patricia Rozema; screenwriter: based on the novel “Mansfield Park” by Jane Austen, and her letters and early journals; cinematographer: Michael Coulter; editor: Martin Walsh; cast: Embeth Davidtz (Mary Crawford), Jonny Lee Miller (Edmund Bertram), Alessandro Nivola (Henry Crawford), Frances O’Connor (Fanny Price), Lindsay Duncan (Mrs. Price, Lady Bertram), Harold Pinter (Sir Thomas Bertram), Hugh Bonneville (Mr. Rushworth), Sheila Gish ( Aunt Norris), Justine Waddell (Julia Bertram), Victoria Hamilton (Mariah Bertram), James Purefoy (Tom Bertram), Hannah Taylor-Gordon (Young Fanny); Runtime: 110; Miramax & BBC Films; 1999-UK/USA)

“This is merely another attempt at making a high-class art film that can’t come close to the spirit of the literary book it is based on.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

In Canadian director Patricia Rozema’s daringly modern adaptation of Jane Austen’s third novel, “Mansfield Park,” the heroine is not the typical timid heroine the author portrayed in her novel, but one who becomes swelled with confidence as a liberated woman. The unworldly young girl becomes a picture of moral rectitude after living in the luxury of Mansfield Park, away from her poverty-stricken Portsmouth family of 1806.

Fanny Price (played by Hannah Taylor-Gordon as a child and Frances O’Connor as an adult) gravitates to her role with a pleasant Mary Poppins sort of radiance, as she is the 12-year-old poor relation niece who is the household servant and second-class citizen in the rich household. She is always reminded by the household of her inferior position. But, by changing environments, she is able to learn how to become a cultured young lady and avid reader and acid-tongue judge of character, noting the hypocrisy of the upper-classes as they pretend to be so civilized yet afford their lavish lifestyle only because of the profits from the slave business they are in. She finds her isolation here is made bearable by her consumate letter writing to her sister and by keeping a diary, and by being smitten by the patriarch’s son.

This book was supposedly the most autobiographical one of all the author’s books. The big-budget costume period piece drama, plays like a production from “Masterpiece Theatre” with all its vices and virtues (with more vices than virtues).

The film takes all the carefully observed reactions and the wit of the morally superior heroine, and makes the plot into a formulaic underdog movie where it is impossible to root against her. Fanny is the only sympathetic character in a household of pompous snobs of varying degrees. Her Aunt Norris (Sheila Gish) is pictured as the most wretched of them all, because she is an inflexible and bitter woman. The patriarch is Sir Thomas Bertram (Harold Pinter), an insensitive, authoritarian and hypocritical man, who could express kindness only on his terms. He makes his money from slavery. His simpleton wife (Lindsay Duncan) spends her time imbibing laudanum quaffs. Their two daughters (Victoria Hamilton & Justine Waddell) are lacking in character and seem to be spending a busy life doing nothing. The oldest son is a party animal, whose rebellion against his father is fraught with deceit and hatred. While the younger son, Edmund (Jonny Lee Miller), is the best of them all, even if he isn’t the most aware person and can’t follow his heart’s dictates for the love Fanny has for him. He, at least, complements Fanny’s sensitivity to the issues of the day and shares her love of language and literature. But he falls for a very attractive but insincere woman who just arrived from London with her handsome brother, Mary Crawford (Embeth Davidtz). She has a cold heart and is drawn to Edmund because she sees an opportunity to marry into wealth. Her sweet-talking, flirtatious brother Henry (Alessandro Nivola), has designs on Fanny. But she resists him and resists the lesbian designs his sister has on her. She rejects him thinking of him only as a rake, even as he is relentless in his pursuit of her. He evidently loves the challenge of the chase, trying but unable to convince her that he is a changed man from the one she saw flirting with an engaged woman and all the other women in the household.

In one ridiculous scene Fanny is sent back to her mother’s insect infested house, after she rejected the proposal of the charming but superficial Henry despite Sir Bertram’s approval of the marriage. This disappointed Sir Bertram, as it challenged his authority to have complete control over everyone in his household. Her mother, trying to encourage the marriage says: “There is no shame in wealth,” whereas Fanny replies “It depends on how it is arrived at.” And the mother says, “Remember, I married for love.” These soap opera lines, leave this lush looking film hanging its hat on a modern and audacious Jane Austen revision; but, it doesn’t work because the film seems disengaged. What we get is not worthy of anything but pulp, as it hits us over our head with trite romantic situations and erotic scenes that are not very erotic. The story seemed flat and not worth making such a big fuss over. It lost all its literary qualities on film. It also seemed lost in Frances O’Connor’s goody-goody portrayal, one that has no stillness in her center as her actions seem more priggish than made out of a deep and firm commitment. It was brought out in the novel that her strength was in her quietness and firm responses. Here, her responses are loud and seem to call attention to herself in a self-righteous way.

This is merely another attempt at making a high-class art film that can’t come close to the spirit of the literary book it is based on. My complaint is not that it drifted away from the book, but that the film can’t begin to get at the inward plight Fanny was struggling through; and, it fails to get underneath the hedonistic family and their connections to the slave trade business. The argument against slavery seemed to be a tacked on one that mirrors more the politically correct position to it found in the 20th century, rather than the way a 19th century heroine living in a pre-Victorian household would respond to it. In the book, Fanny complained whenever she brought up the subject with the patriarch, she was met by silence.

REVIEWED ON 1/23/2001 GRADE: C