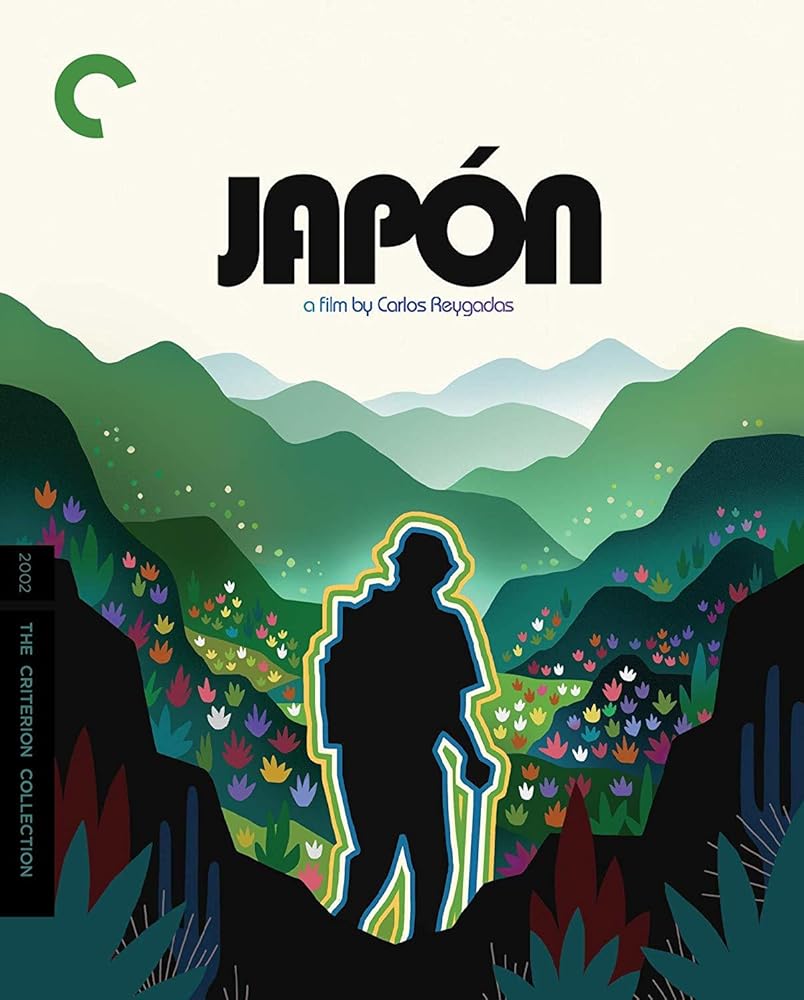

JAPÓN (JAPAN)

(director/writer: Carlos Reygadas; cinematographer: Diego Martínez Vignatti; editors: Carlos Serrano Azcona, Daniel Melguizo and David Torres; music: Arvo Pärt/Dimitri Shostakovich/Johann Sebastian Bach; cast: Alejandro Ferretis (the Man), Magdalena Flores (Ascen), Yolanda Villa (Sabina), Martín Serrano (Juan Luis), Rolando Hernández (The Judge); Runtime: 122; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Carlos Reygadas; Vitagraph/American Cinematheque; 2002/Mexico, in Spanish, with English subtitles)

“An obscure and haunting and unpredictable parable.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A haggard-looking man (Alejandro Ferretis) in his sixties with a limp and dark brooding eyes travels from the big city to a remote mountainous field and asks the help of bird hunters the way to a small village located at the bottom of a canyon called Aya (It was shot in the Mexican state of Hidalgo). The hunter asks the old man, “Why are you going to such a ghost town?” He replies, “To kill himself.”

The 31-year-old Mexican writer-director Carlos Reygadas, in his first feature film, creates an obscure and haunting and unpredictable parable covering the same themes as Abbas Kiarostami’s 1997 ”A Taste of Cherry.” Both films are ambitious, strange, unclear and unsettling. Mr. Reygadas’ landscape is allegorical and his story is timeless and plotless. The stark landscape of cacti, dirt, stones, grazing sheep, and the brooding silence of the main character, set a mood of doom and deep reflection and mysticism. The cast of all nonprofessional actors play the parts of the peasants which is their role in real life, except for the nameless stranger who seems to be an educated man (supposedly a friend of the director’s family).

The film was shot in Super 16 Scope. Shostakovich’s final movement from his 15th and Pärt’s Cantus, adds intensity to the already mesmerizing visuals. But there are also elements in the deliberate pace and purposeful vagueness that seem too arty, and left this viewer a bit addled that the film seems unfocused at times. Japón’s uniqueness is not that it breaks new ground but that it plays like an Andrei Tarkovsky meditation study and also features a Christ motif and familiar religious symbolism, yet it can’t be reined in as either brand new or old hat. Instead, it feels heavy and studied and is shaped into an objective work of art. The young director is more concerned with ideas than in understanding his characters or in telling a good story.

The Man meets the Judge in the canyon town, who arranges for him to secure lodging in a rundown stone barn with a poor old Jesus-believing woman, Ascen, who lives in an adjoining hut in a remote area on the outskirts of town that overlooks the canyon. We learn that her name stands for Ascension, which refers to Christ ascending into heaven with no one’s help. The Man who professes no religious beliefs prefers listening on his Walkman to Bach than praying like she does. The Man’s probably an artist, as he paints the landscape and gives the drawing away to an inquiring child. He mentions that he came here as a child on vacation. Assisted by his cane and wearing a red flannel jacket, he slowly hobbles down to explore the canyon. The Man’s met by a hostile local named Juan Luis, who calls him “a nosy bastard.” Ascen mentions that’s her nephew and that he wants to take the stones from her barn to sell them in town. By tearing down the barn, her hut will no longer be protected from the weather and it will be unlivable. Apparently, the nephew does not care that the peaceful seventysomething widow who has lived there for 40 years will in effect have no place to live. She says it was his grandfather’s house and he has the right to take it back. Hearing that, the Man gets agitated and comes to life for the first time since his visit. He turns Ascen on to marijuana and when asked why he came here, says it was for the calm. The Man later retreats to his bed to masturbate, and dreams of a beautiful woman and of the sea. The Man thinks of shooting himself, but can’t. When outside, The Man still can’t pull the trigger. In town the Man gets drunk on mescal. On his return, the Man tells Ascen he would like to have sexual intercourse with her. Ascen is nonplussed, but tells him to wait until tomorrow. Ascen first wants to visit the church and let Jesus in on her little misadventure. Ascen senses his gloom and has the most rational line in the film. Ascen tells the Man: “Even though I don’t like my arthritic arms, I won’t chop them off.”

There are many long tracking shots and long takes, which allow the viewer much time to muse over what might be happening. An unseen pig is killed and cries out in pain, horses copulate as giggling children watch, a small dog is forced to sing along with a drunk member of the crew that knocked down the stone barn and sings so off tune that it’s almost bearable, and one drunken crew member complains that this liquor is all that the film company gave them. It all seems like a perverse joke. But this temporary suspension of disbelief from the drunken crew ends in a weirdly apocalyptic manner, where the locals have become swept up in a natural force that is beyond their comprehension while the stranger has found in this alien setting a renewed sense of life from his rediscovered emotions.

The film’s aim was to carry us deeper into the world and not escape from it through art or pleasure, as Reygadas’s sublime film accomplishes that and also makes us thirsty about knowing something about ourselves we cannot say without shocking the other person. Japón is ultimately about redemption and conquering one’s nature. It’s about uncharted spiritual love. In its sparse dialogue and intensity it is mindful of a Robert Bresson film, yet Reygadas is less grounded in myth but more free-flowing and harder to fence in. The young Mexican filmmaker loves the wide open spaces and the breaths of his protagonist that take him to the edge of the world, where he must choose between love or death. I would guess that the strange title doesn’t refer to a place, but to the distance one must travel to find peace of mind.

REVIEWED ON 7/28/2003 GRADE: A –