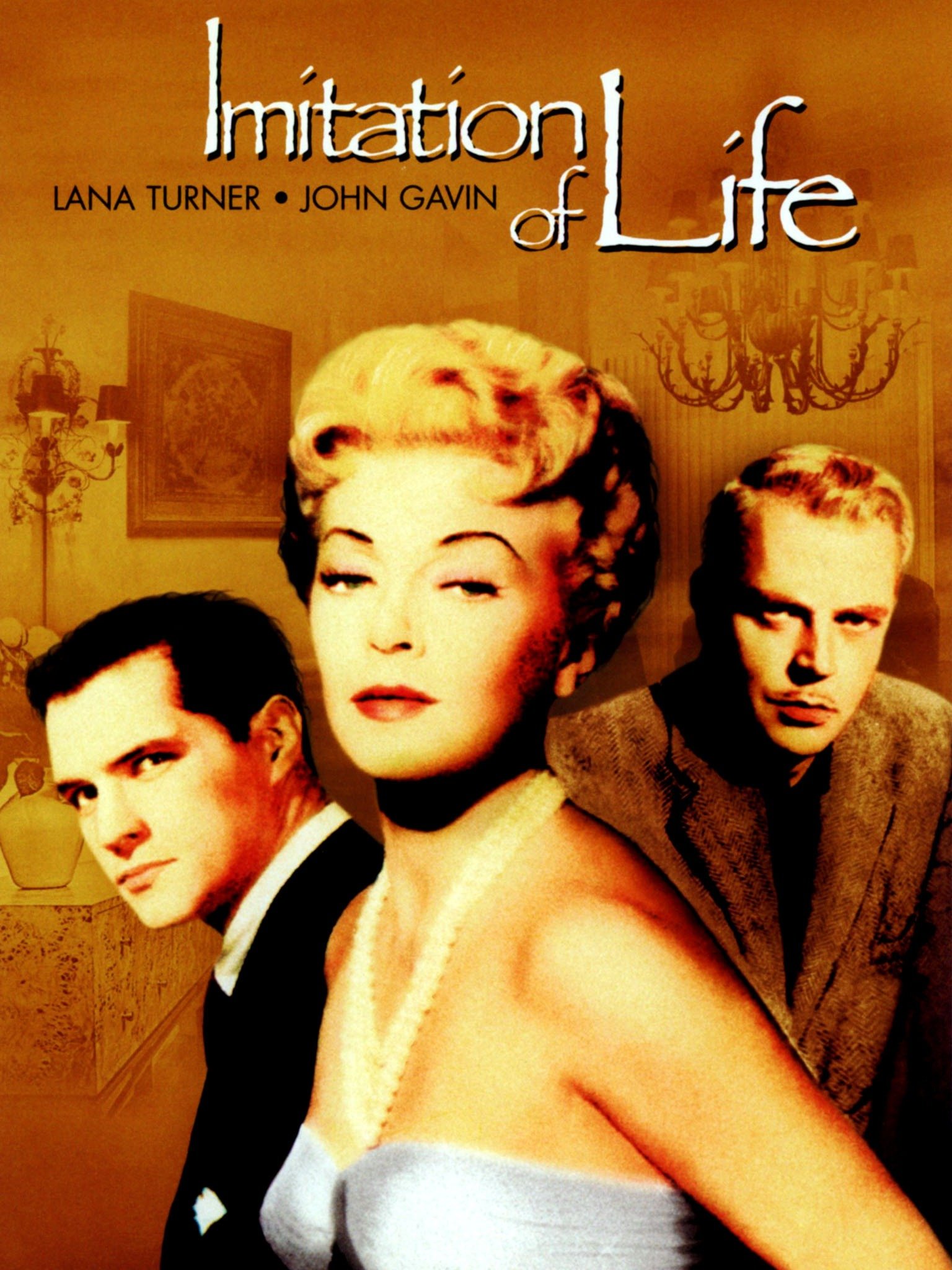

IMITATION OF LIFE

(director: Douglas Sirk; screenwriters: Eleanore Griffin/Allan Scott/based on the novel by Fannie Hurst; cinematographer: Russell Metty; editor: Milton Carruth; music: Frank Skinner; cast: Lana Turner (Lora Meredith), John Gavin (Steve Archer), Sandra Dee (Susie), Terry Burnham (Susie, Youngster), Juanita Moore (Annie Johnson), Susan Kohner (Sarah Jane), Karin Dicker (Sarah Jane, Youngster), Daniel O’Herlihy (David Edwards), Robert Alda (Allen Loomis), Troy Donahue (Frankie), Mahalia Jackson (Choir Soloist); Runtime: 125; Universal-International; 1959)

“Intelligent and compelling.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Even though he was only 60 years old, this is Sirk’s goodbye film to America. Sirk was born of Danish parents in Hamburg, Germany and retired to live in Germany for the last 25 years of his life.

Sirk’s film is a re-make of John Stahl’s 1934 Imitation of Life. Producer Ross Hunter convinced the Ice Queen, Lana Turner, to make her comeback with nurturing director Sirk. It was a return to stardom for Lana after her 1958 sordid love affair with low-level gangster Johnny Stompanato, who was slain by her daughter over a lover’s triangle.

This weepie melodrama turned out to be a commercial success despite some bad early reviews, it was Universal-International’s biggest money maker for that year. It was also its biggest grossing film until Airport, yet for all its crowd pleasing melodramatics it is also a very intriguing and analytical work that demands attention.

Sirk’s film is all of the following: a social consciousness exercise about America, a look at the breakdown of the nuclear family because of materialism, a tale about being a good mother, an exploration about what people strive for in their careers and in their love life, and a probe into issues of life and death. It’s also a film that sharply examines America’s racism through a light-skinned black girl who wants to pass for white. It’s a weird film that defies what it is. Everyone has a different view about life from the person they are close to and they are all unfortunately blind to the other’s view. There’s an underlying cynicism to the soap opera story, despite the attempt to give it a happy ending.

The film opens in the Coney Island of 1947 and a frantic mother, Lora Meredith (Lana Turner), has lost her 6-year-old daughter Susie on the crowded beach. She’s found playing with an almost white girl age 8, Sarah Jane, who is taken care of by a black woman, Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore), whom Lora mistakes for the maid. When told by her that she’s the mother, the surprised Lora falters but then accepts it without a question as if it were a natural thing that a black woman has a white child.

Lora is a thirtyish widow. Her husband was a community theater director who came from a small town in the sticks to become a Broadway star, while Annie is an older widow who is homeless. Also on the beach, trying to help Lora find her child is a handsome aspiring photographer, Steve Archer (John Gavin). This chance meeting will bring all parties together. Lora, who is unemployed and struggling to make ends meet, takes Annie and her child back to her apartment to be a live-in maid. The saintly Annie is troubled that her daughter is ashamed of being black and tries to pass herself off in school as white. Annie says: “It’s a sin to be ashamed of what you are — and it’s a sin to lie about who you are.” The most shameful incident for Sarah Jane, something she will always shamefully remember, takes place in school when Annie arrives in her class to bring her an umbrella because it is raining. The girl never forgives her for embarrassing her in front of her classmates by letting everyone know she’s colored.

Lora is obsessed to be a star, and in her pursuit neglects the daughter she loves and spurns the love of Steve. He wants to marry and to support her, he’s willing to give up his artistic aspirations to take a job as a photographer with an advertising place. This is something that Lora can’t understand, as a career is more important to her than love. Susie is raised by Annie, as Lora’s career gets a boost by sleazy agent Allen Loomis (Robert Alda). He can’t induce her to cheapen herself for a part, but he accepts her independence in order to get his ten percent and hooks her up with successful playwright David Edwards (O’Herlihy). In her first role, in a play called Stopover, she gets good reviews in a minor role. This propels her to stardom and for the next ten years she moves in the fast-lane of the theater, where she’s romantically involved with Edwards. Her cravings are not for money or love, but to be a success in her chosen career. Steve has disappeared from her life after stupidly giving her an ultimatum to marry him and forget about her career. He has not seen her for the last ten years, but still loves her. He suddenly reappears when Lora is tired of the roles she’s playing and stars in an arty theater work not written by David Edwards. It appears they might be getting back together again, but a new offer arrives for her to be in a film by a noted Italian film director. She quickly forgets about Steve and is packing to go to Italy, which sends Steve away again.

Both girls have grown up and are rebelling against their mothers. Susie chooses to go to college in Denver, far away from home. Sarah Jane meets a white boy, Frankie, who beats her up when he finds out she lied to him about being white. Sarah Jane blames her mother for ruining her life and escapes from home to go to Las Vegas to be taken for a white chorus girl. When Annie tracks her down and goes to see her there, she realizes that she can’t live her life through the girl any longer and must let go even though she deeply loves her. She promises to never embarrass her anymore by saying she’s her mother.

The film culminates with Annie’s death, as Lora is surprised that Annie is dying and leaving her alone in the world to face her troubles. When she lifts her head in tears over the bed of the dying maid, we see in the background a photograph of the smiling Sarah Jane. At last the girl seems to be free of her mother and can be who she wants to be. Annie’s only wish now, is to have a big funeral.

All the characters want what is best for themselves, even if it doesn’t seem to do them much good. Annie gets her big funeral, but since she’s dead it doesn’t do her much good. She only wants it because it will give her an importance she never had in life. Lora gets to be a star, but her life is far from satisfactory. At the funeral everyone comes together again, and it seems like everything will be all right. But even as Sarah Jane forgives her mother when she’s dead as she hysterically throws herself on the casket, we realize that you can’t change the world or the way people are. That the same people who you think have changed will revert back to messing up their lives as they always do. Sarah Jane wants to be white because she thinks you can live better as a white person. Lana wants to be an actress not because it is what is right for her, but because she will have a better status in the world. Sandra Dee falls in love with John Gavin, who might be right for her. But he thinks he only wants Lana. Poor Sandra Dee can’t understand why he doesn’t respond and decides that it is best to run away from her past. These characters are unaware of how they are manipulated by their social reality and that they have not found their true journey in life. What they are all doing is an imitation of life. They are too unmindful of others as well as their own self to find true peace in this world. It becomes apparent that Lana Turner knows little about Juanita Moore, even after living together for ten years. When Juanita tells Lana she has many friends and interests, Lana can only act surprised like she does about everything that happens to her. Lana’s entire life is one big surprise, in this surprisingly intelligent and compelling film.

At Annie’s ornate funeral Mahalia Jackson sings a heartfelt rendition of “Trouble of the World.” The film earned Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner Academy Award nominations. Over the course of time, many have come to consider this as a great film about post-war America–something the public recognized before most of the critics did.

REVIEWED ON 1/29/2002 GRADE: A