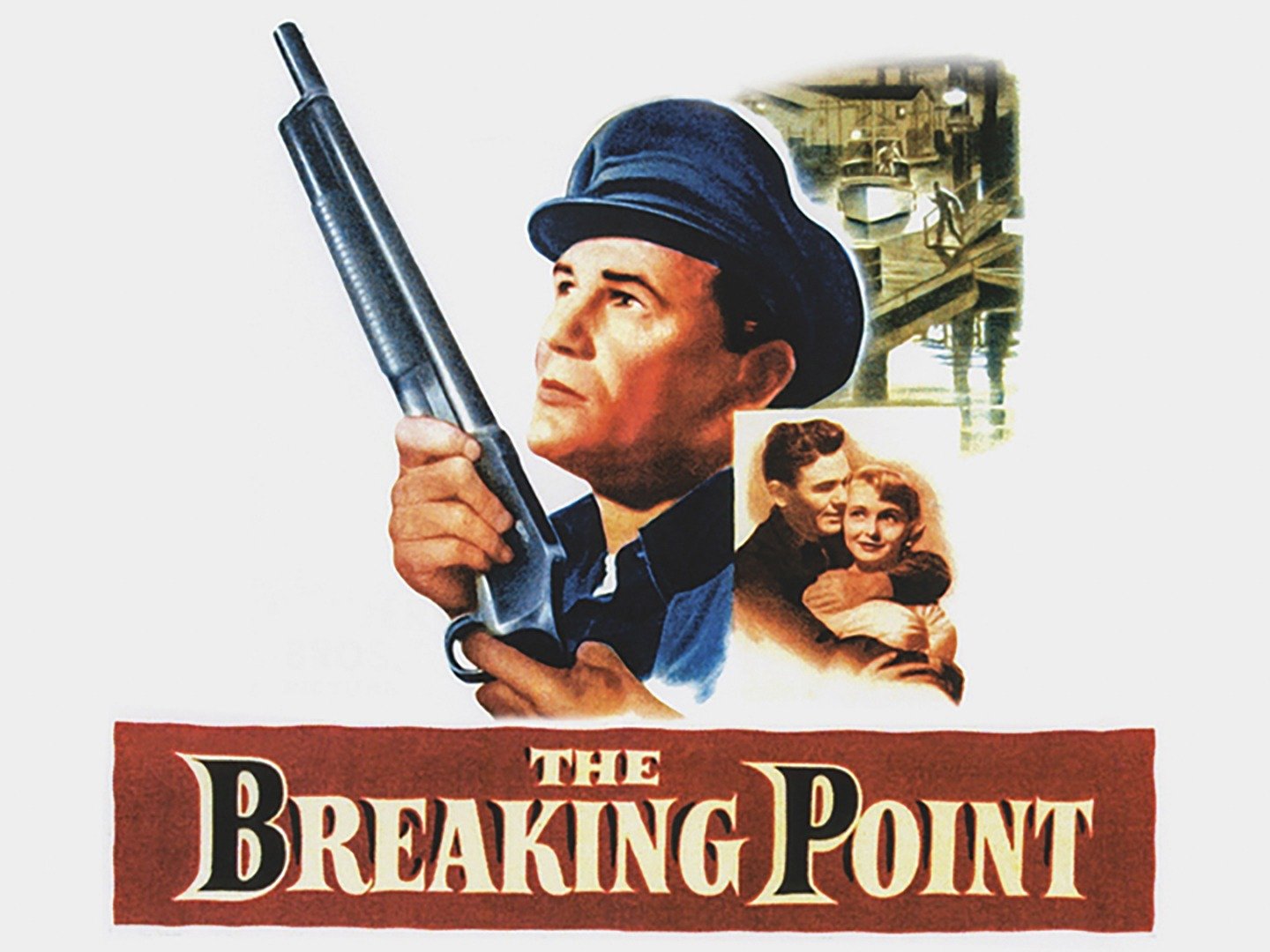

BREAKING POINT, THE

(director: Michael Curtiz; screenwriters: from the novel “To Have and Have Not” by Ernest Hemingway/Ranald MacDougall; cinematographer: Ted D. McCord; editor: Alan Crosland Jr.; music: Ray Heindorf; cast: John Garfield (Harry Morgan), Patricia Neal (Lenora Charles), Phyllis Thaxter (Lucy Morgan), Juano Hernandez (Wesley Park), Wallace Ford (Duncan), Edmon Ryan (Rogers), Ralph Dumke (Hannagan), Victor Sen Yung (Mr. Sing), Alex Gerry (Mr. Phillips); Runtime: 97; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Jerry Wald; Warner Brothers; 1950)

“Clearly the best movie adaptation of a Hemingway novel.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Clearly the best movie adaptation of a Hemingway novel. Hawks in his 1944 To Have and Have Not which starred Bogart and Bacall, came close to getting it right. Michael Curtiz (“The Sea Hawk“) six years later was more faithful to the author in his remake. He was better able to catch the spirit of the fatalistic charter boat captain who wrestled with his inner demons until he reached his breaking point and found out for sure what kind of man would emerge. The great émigré studio director played the story straight as written and got one powerful performance from John Garfield and tremendous complementary performances from the ensemble cast, especially from Wallace Ford and the soon to be star Patricia Neal.

Garfield was always known as a politically active liberal, who was one of the few actors to force the studios into hiring minorities. He later on paid the price for his activities as he became one of the most famous of Senator McCarthy’s Hollywood blacklist victims, which virtually ruined his career and sped up his early death at the age of 39. During his time, actors were usually not that outspoken. His leftist causes were not popular with the nervous studio heads who were worried about losing business in Dixie, but because he was such a big box-office hit they kept giving him great parts. In “Breaking Point” he convinced Curtiz, who happened to be his favorite director and the one he credits for making him a star — he was cast as a supporting actor in Four Daughters in 1938 — to expand the part of the black man Juano Hernandez. His role took on a greater importance than the more usual stereotypical Hollywood role of the time, where the Negro was usually either the chauffeur or in some other servant role.

Harry Morgan (John Garfield) is a struggling charter boat captain of the Sea Queen. He resides in Newport, California, where he is happily married to Lucy (Phyllis Thaxter) and is a good father to his two sweet young daughters. But he’s bogged down by financial problems. He still owes money on the boat and has other serious debts, and business is so bad that his family is fed only because his wife works as a seamstress. Along with his best friend and first mate, Wesley Park (Juano Hernandez), he takes a sugar daddy named Hannagan (Dumke) and his sexy girlfriend Lenora Charles (Patricia Neal) on a week long charter fishing cruise to Mexico. In a Mexican port town Hannagan stiffs him and flees the country by plane, also dumping the broke Lenora. With no money to buy fuel to return, the straight-arrow captain bends the rules he lives by and takes the offer of a shyster lawyer named Duncan (Wallace Ford) to help his client smuggle into the States eight Chinese illegals for $1,600. The risk if caught is the possibility of ten years in jail. But Harry feels cornered and sees no way out except to make the deal with the untrustworthy Mr. Sing (Victor Sen Yung). He gets double-crossed when Sing refuses to pay in full after the eight are on board. Harry wrestles the gun away and in the ensuing struggle kills him, and Wesley helps dump Sing’s body overboard. The Chinese who were below deck have no idea that Sing was murdered, and are given back the $300 they gave Harry and are forced off the boat at the same shallow water spot they were picked up. Upon his return, the Coast Guard impounds his boat on the request of the Mexican authorities on the suspicion of smuggling illegals. Without his boat, the restless Harry waits at home with nothing to do but worry about making his long overdue boat payments to a pressuring Mr. Phillips.

Again Harry gets sucked into getting help from the cunning Duncan who, acting on his own as a lawyer, gets Harry’s boat back on a court order. Duncan then arranges for the desperate Harry to take another illegal charter party. The price is a thousand dollars to take four gangsters to Catalina Island after they rob the racetrack.

While waiting to take the gangsters, Harry’s head is spinning around and in a drunken state he’s tempted to take up Lenora on her offer of unconditional sex. But his heart isn’t in it, so he returns home and leaves his wife the money the gangsters gave him upfront and has a row with her over his unwillingness to give up the boat and become a lettuce farmer. She threatens to leave him if he goes on this dangerous charter, but he plans on outsmarting the ruthless criminals and thereby collect the expected reward.

Warning: spoiler to follow.

But things don’t go as planned, and the gangsters go on a killing spree forcing him to get into a shootout with them on the boat. As a result Harry kills all four, but gets severely wounded and passes out while mumbling to himself how he is so alone and doesn’t care if he dies. The Coast Guard cutter rescues Harry, and when he reaches port he is surprised to find Lucy there. She tells him how much she loves him, and he now agrees to let the doctors amputate his wounded arm or else he would have died.

In this brilliant version of Hemingway’s story, the nagging feeling of futility persists for our archetypal noir hero despite having strong family support. It’s only when this action hero character hits the absolute bottom, despite his tough outward persona, that he realizes his defeatist attitude and vulnerability and undue capacity for suffering have reached a point of do or die. It’s hard to put the gut-spilling performance of Garfield out of my mind, as his realistic portrayal captures all the heartfelt cynicism and force of the character.

This is Curtiz’s greatest picture, though not as popular as some of his others. It’s even greater than his noted classics Casablanca or Yankee Doodle Dandy.

REVIEWED ON 3/28/2003 GRADE: A