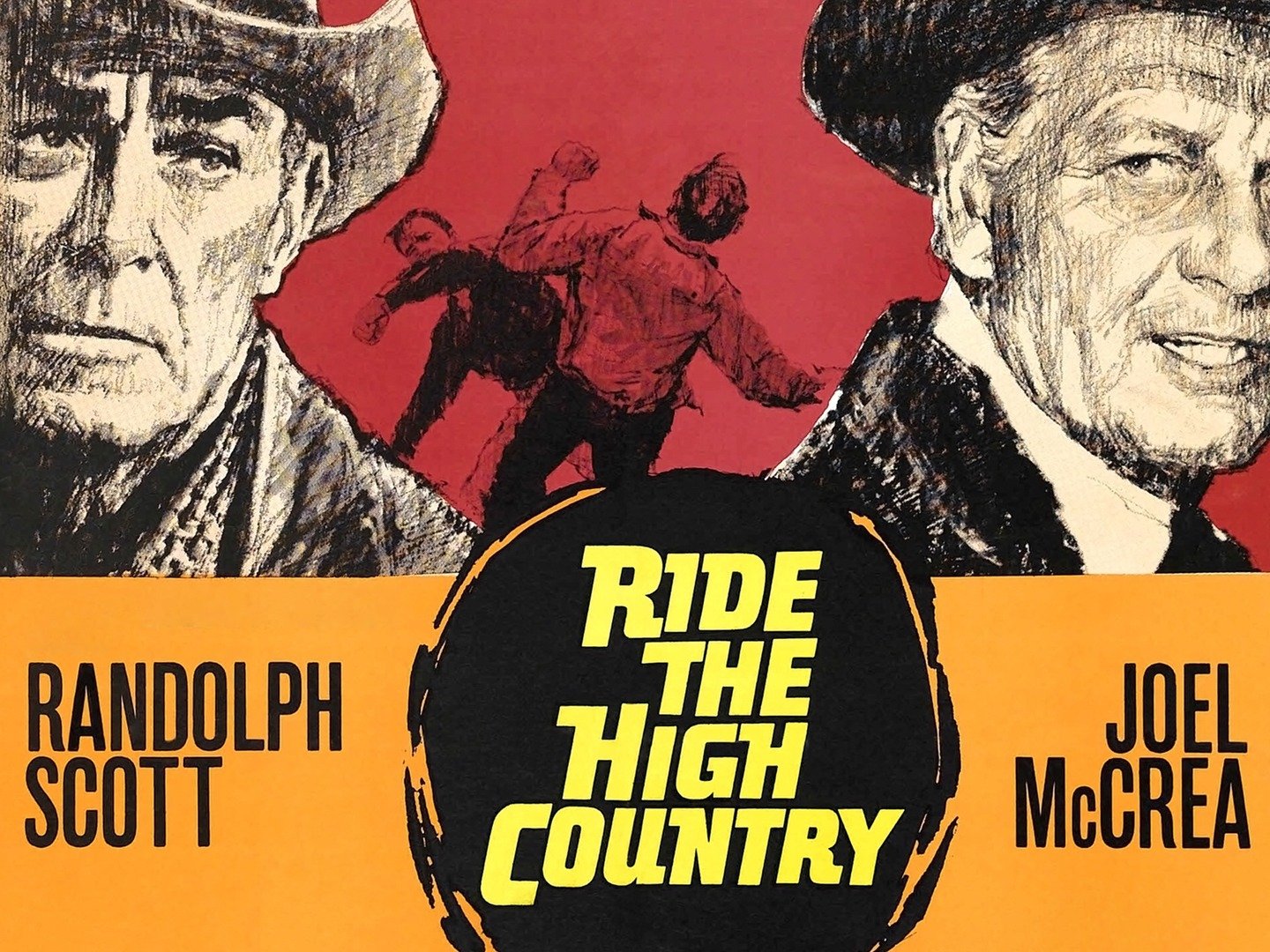

RIDE THE HIGH COUNTRY

(director: Sam Peckinpah; screenwriter: N.B. Stone Jr.; cinematographer: Lucien Ballard; editor: Frank Santillo; cast: Joel McCrea (Steve Judd), Randolph Scott (Gil Westrum), Mariette Hartley (Elsa Knudsen), Ron Starr (Heck Longtree), James Drury (Billy Hammond), Edgar Buchanan (Judge Tolliver), R.G. Armstrong (Joshua Knudsen), Warren Oates (Henry Hammond), L.Q. Jones (Sylvus Hammond), John Anderson (Elder Hammond), John Davis Chandler (Jimmy Hammond), Jenie Jackson (Kate), Percy Helton (Luther Sampson); Runtime: 93; MGM; 1962)

“A superior Western featuring two of that genre’s greats, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott, who were both in their 60s at the time…”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A superior Western featuring two of that genre’s greats, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott, who were both in their 60s at the time and both accumulated a great deal of wealth due to their wise investments in oil and real estate and livestock. This film was meant to be their swan song but McCrea was talked out of retirement to play a few insignificant parts later on, before retiring from films and becoming one of Southern California’s wealthiest ranchers. This low-budget Western appealed to both stars because it was really a homage to their long careers–where their combined film total must be over a few hundred. They would be playing aging gunmen, an extension to the many different characters they played in their long film life. They were also impressed with their young director Sam Peckinpah who had made only one feature before in 1961, “Deadly Companions.” Because of their terrific acting skills and Peckinpah’s stylish direction, this film turned out to be one of the better Westerns ever made.

The aging Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) just hired by the bank, despite them being skeptical that he’s too old for the job, recruits his longtime ex-deputy, the aging Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott), now working in a carnival, into helping him transport a gold shipment from a mining camp to the city bank. Heck Longtree (Ron Starr) is the junior partner of Scott’s and, against McCrea’s better judgment, is talked into being a part of the security team. Heck is wild, irresponsible, hot-headed, and women crazy — but, he fits the pattern of the senior citizen’s own wild youth.

When Scott hears from McCrea that there might be as much as $250,000 in gold from the miners he makes plans with Heck to rob that money, hoping he could talk the straight arrow McCrea into going along with his scheme by filling him with stories of how underappreciated and underpaid they were as lawmen and now have nothing to show for it. But he soon realizes that he can’t talk him into it.

On their first stopover in their two day trek to the mining camp, they stay at an isolated farmhouse where resides a stern, embittered, widower (R. G. Armstrong) and his attractive young daughter Elsa (Mariette Hartley-her debut in films). Elsa is kept under wraps by him. At dinner her father is rigidly quoting scripture, getting into a duel of scriptures with McCrea. When he spots her talking to the flirtatious Heck in the barn area, someone she is attracted to, he reacts by striking her. The next morning Elsa sneaks away from the farm and joins the bank guard trio telling them she’s going to the mining town to marry her fiancé Billy Hammond (James Drury), someone her father refused to let her see.

At the mining camp, Elsa’s marriage to Billy turns out to be a disaster. Billy and his redneck brothers (Oates, Anderson, Chandler and Jones) are brutish swine. Elsa wants to back out of the honeymoon suite which is lodged in the local whorehouse run by Kate (Jackson), where all the brothers try to be the first to consummate the marriage in a Biblical sense. She gets rescued by the puritanical McCrea, who promises to take her back to her father. In order to get her to leave the camp with the bank guards, the pragmatic Scott sticks a gun in the drunken judge’s (Edgar Buchanan) ribs and steals the marriage license. After a miner’s court hears the case and they see no license, the miners who outnumber the trio–allow her to leave.

But on the road back, with the $11,000 in gold–not the high amount of money Scott expected, the men become conflicted as McCrea catches the two trying to steal the gold and ties them up, promising to take them to the town sheriff. The other problem is that the Hammond boys come after Elsa and the gold, as it turns out they were the robbers the bank feared.

These two old time gunmen realize that their time has come and gone. In town there are horseless carriages and Chinese restaurants, and they plainly see the signs pointing to them as dinosaurs. For McCrea this bank job becomes a way for him to gain back the self-respect he has lost, after years of working in various saloons as a bouncer; while for Scott, the gold is his one chance to get some big money for his retirement. But as it turns out this job gives both of them a chance to look again at their values, and through the plight of Elsa they see things are not always black or white. Both are forced to change their opinions. In the end they come to their senses, standing together as they shoot it out with the Hammond boys to protect the gold, Elsa, and their honor.

The film won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. This is one of Peckinpah’s more appealing films. It is visually stunning, fully capturing the gorgeous mountain landscapes in comparison with the more gaudy view in the modernized town. It is also Peckinpah’s warmest portrait he paints of a woman’s sufferings in any of his films, as one can only feel pity for the sexually repressed Hartley who lives in such a backward frontier settlement.

REVIEWED ON 3/8/2001 GRADE: A