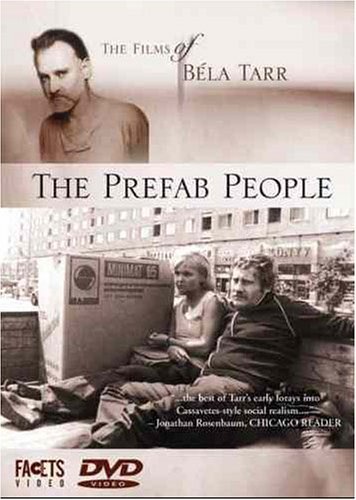

PREFAB PEOPLE, THE

(director/writer: Béla Tarr; cinematographers: Barna Mihok/Ferenc Pap; editor: Agnes Hranitz; cast: Róbert Koltai (Robi, Working Class Husband), Judit Pogány (Wife), Gabor Koltai (Son); Runtime: 82; MPAA Rating: NR; Facets Films; 1982-Hugarian-in Hungarian with English subtitles)

“It’s the rawness of the film that makes us believe we are unquestionably seeing the truth.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

A heavy going realistic slice of life domestic drama that is filmed in black and white. It’s a followup to Béla Tarr’s other domestic strife tales Family Nest and The Outsider. This one keys in on marital strife. It’s about a struggling young couple’s confrontations and their own inability to freely communicate with each other. Tarr was evidently influenced by the works of Ranier Werner Fassbinder and John Cassavettes.

The film opens with factory worker hubby packing his bags and abruptly walking out on his hysterical wife. The young couple have two small children. In the next scene, the wife recalls events in their marriage such as a squabble celebrating their wedding anniversary over her complaints she does the housekeeping and takes care of the children and he offers no help and doesn’t communicate with her, and another spat at an outing to the pool when wifey is ticked he left her alone for over an hour to talk with his friend. At a dance, hubby dances with another woman and wifey jealously stares into space as the song played is “I’ve got a black baby.” The only time hubby is seen talking with his older school-aged son he gets mixed up trying to explain the difference between capitalism, socialism and communism. Hubby is offered a tour of service in Romania for two years to work at the same control room position he has and with double pay, but wifey refuses to be left alone. The film then returns to the opening scene and we now understand why hubby is leaving so abruptly. With hubby returning from abroad, we next see the couple purchasing a new washing machine in celebration of their reconciliation but returning from the store after the purchase looking as depressed as they usually do.

The unrelenting confrontations between a nagging wife and a distant hubby, where the filmmaker takes no sides in showing this downbeat marriage, gives one a picture of how the ordinary Budapest resident of the 1970s and early 1980s lived under communism. It’s not a pretty or entertaining picture, but it does scratch at the surface of things to show that not everything that is deep has to be complex. It’s the rawness of the film that makes us believe we are unquestionably seeing the truth.

REVIEWED ON 8/9/2005 GRADE: B