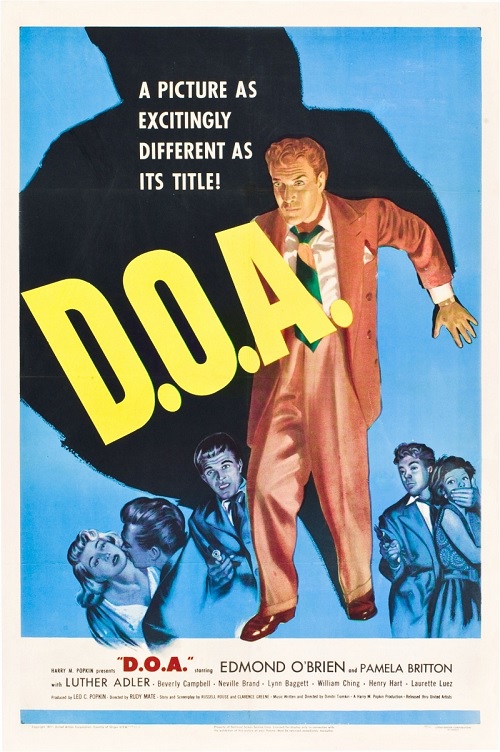

D.O.A.

(director: Rudolph Maté; screenwriters: Clarence Greene/Russell Rouse; cinematographer: Ernest Laszlo; editor: Arthur H. Nadel; music: Dimitri Tiomkin; cast: Edmond O’Brien (Frank Bigelow), Pamela Britton (Paula Gibson), Luther Adler (Majak), Beverly Campbell (Miss Foster), Lynne Baggett (Mrs. Philips), William Ching (Holliday), Henry Hart (Stanley Philips), Neville Brand (Chester), Laurette Luez (Marla Rakubian), Jess Kirkpatrick (Sam Haskell), Frank Gerstle (Dr MacDonald), Lawrence Dobkin (Dr. Schaefer), Fred Jaquet (Dr. Matson); Runtime: 83; MPAA Rating: NR; producer: Leo C. Popkin; United Artists; 1950)

“Features a murder victim who acts as a detective to solve his own murder.”

Reviewed by Dennis Schwartz

Polish-born Rudolph Maté, the cinematographer for The Passion of Joan of Arc and Vampyr, in his directorial debut helms a beauty of a film noir classic that uses to its advantage the protagonist’s despairing comment about his dire situation “All I did was notarize a bill of sale…”.

D.O.A. (a police abbreviation for ‘dead on arrival’) is inspired by Robert Siodmak’s 1931 German film “Der Mann, Der Seinen Morder Sucht,” which tells about a dying man’s quest to find the cause of his oncoming unnatural demise. Maté used the same delirious plot and encompassed it by illustrating the corrupt nature of society and the cynicism, chaos and alienation among the restless people striving for wealth and pleasure. It is changed only from the original German film to point to the dark vision foreseen in modern postwar America and its emerging middle-class of hard-working and hard-playing business people. D.O.A. looks closely at the traps people fall into as forces they have no control over can snare even those who think they are immune from tragedy, such as what happens to the film’s hero. It is through this existential outlook that D.O.A. captures the imagination. It features a murder victim who acts as a detective to solve his own murder. Film noirs never start from a more unique premise.

Ernest Laszlo’s creative expressionistic photography enhances the nightmarish journey the ‘everyman’ victim is going through, as he becomes enmeshed in the intensity of life in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Clarence Greene and Russell Rouse provide the thrilling screenplay.

The film opens with Frank Bigelow (Edmond O’Brien) rushing into a police precinct and telling the homicide captain “I want to report a murder…mine.” The officer doesn’t seem surprised since hospital doctors already reported Frank’s murder, so the captain lets Frank tell his story as the film goes into flashback.

Frank is an accountant running a small business in Banning, California, who goes for a week’s vacation in San Francisco. He can’t wait to get away, as he’s become weary with his humdrum life and is not sure if he wants to marry his loyal fiancée and secretary Paula Gibson. After having a few drinks with hotel guests there for ‘Market Week’ and ogling in a wolfish way the hot chicks at the party, Frank goes at night to a waterfront jazz dive, Fisherman’s club, and gets a dose of jive (great close-ups of the sweaty black jazz musicians and the white crowds trying to take in this hip scene). The next morning Frank wakes up feeling miserable, which he senses is from more than a hangover. At the doctor’s office he is told that he’s been given an iridium poison (“luminous toxin”) and there’s no antidote available, and has from a day to as much as a week to live. When Frank is in a daze about what’s happening to him and finds it too incredible to believe, the doctor says “I don’t think you fully understand, Bigelow. You’ve been murdered.” Rather than report to the hospital and wait to die, Frank retraces his steps since arriving in San Francisco and becomes determined to find the killer who slipped the poison into his drink.

How Frank goes about solving the mystery involves a series of ingenious twists as he traces a shipment of iridium from a legitimate L.A. chemist, Eugene Philips, who asked him to notarize a bill of sales, and further learns how the poison came into criminal hands by bullying his way with Philips’s wife and Philips’ business associates such as the unhelpful controller of the firm Holliday, the secretary Ms. Foster, and Eugene’s brother Stanley. Frank learns that he had been targeted only because he’d notarized that bill of sales and therefore one of the criminals feared his testimony could change Eugene Philips’ suicide to a murder case, which would call attention to him as a suspect. How things develop into greater complexities involving the unsavory gangster Majak and get worked out is fascinating, and I will forgo any spoilers so the viewer can fully enjoy seeing the film without knowing what to expect.

All the while Frank is on the hunt, he keeps in contact with his worried secretary but never lets on that he’s already a dead man. Though he will finally discover that he does love Paula, and at least gets a chance to tell her this.

Neville Brand plays a crazed psychopath, whose satisfaction he gets in cruelly punishing his victim, Frank, seemed to match the ecstasy of the pleasure seekers in the jazz club in their pursuit of happiness.

D.O.A. leads us in a breathless pace through the dark spots of San Francisco and L.A. and reveals the intensity felt from a dying man telling his strange story. It spins a web of corruption beyond what Frank could have fully comprehended when he left small town America to take a fling in the big city.

Edmond O’Brien does a superb job of convincingly becoming transformed from an ordinary joe to someone obsessed with tracking down his brutal killer. O’Brien must cast aside his middle-class niceties to become the avenger who will not be denied his last mission in life.

One of the most original and definitive film noirs ever made.

REVIEWED ON 11/8/2004 GRADE: A +